How to determine which works of theatre belong in a canon is a perennial question, especially considering that critics regard the production value of a play and its frequency of performance as more important than its publication. Nevertheless, there are a few works of Peruvian theatre that companies have continually produced since their debuts. One could argue that the frequency of production rather than publication could be a criterion for identifying a type of national dramaturgical canon. On the other hand, a play’s popularity among theatre artists could also indicate its ease of production. Plays that call for simple sets, a few characters, and easily crafted costumes are often chosen for financial reasons. Regardless, this article will be the first in a series to discuss those works of Peruvian theatre that have had an exceptionally long life on the stage. Ipacankure (1968) by César Vega Herrera will open this series.

Ipacankure (1968) by César Vega Herrera

César Vega Herrera (Arequipa 1939) is one of Peru’s longest active dramatists, but possibly the least known among critics of Latin America’s theatre, despite having won the Tirso de Molina prize for theatre for his 1976 work, ¿Qué sucedió en Pasos? and the 1968 Casa de las Américas prize for theatre for Ipacankure. Perhaps the best known of Vega Herrera’s works, Ipacankure is parsimonious in its setting but rich in intellectual content. This one-act play with two scenes delves into the existential philosophies and revolutionary discourses of the late 1960s, which are recurrent themes in Vega Herrera’s oeuvre.

In the play, two characters, UNO (ONE) and DOS (TWO), share a small apartment, not to mention a small bed in which one sleeps feet up and the other sleeps feet down. They also share the same pajama in the script. UNO wears the shirt and DOS wears the trousers, and because of the nakedness of his bottom half, UNO does not leave the bed. The two share everything but argue about everything as well. UNO uses psychoanalysis to dominate the arguments he has with DOS and pushes DOS to a crisis point by threatening to leave the apartment. DOS becomes ridden with anxiety on hearing UNO’s plans because he has become dependent on UNO.

Ipacankure plays on language in a manner reminiscent of the theatre of the absurd, inventing words like “tarupido,” a combination of “tarado” (foolish) and “estúpido” (stupid). In this manner, it invents a separate reality within the space of the theatre and manipulates it before the audience can become too accustomed to the characters’ world. The title of the play, Ipacankure, is another invented word, but unlike the other invented terms in the work, symbolizes the relationship between UNO and DOS. The play’s cryptic ending reflects a common psychoanalytic theme common to many of Vega Herrera’s works from the 1960s.

Theatre companies have typically performed Ipacankure with two male characters, but an adventurous director could attempt this play with two women successfully. Given the depiction of characters’ tense arguments in an enclosed space, a mixed-gender cast would cause the audience to interpret the work’s main conflict as sexual tension. Such a move, in turn, would negate much of Ipacankure‘s existential content.

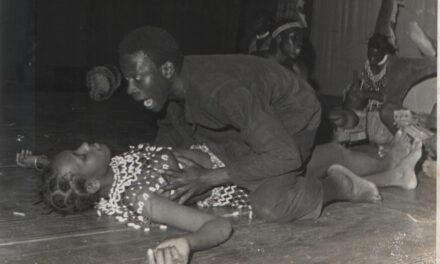

The Teatro Universitario de la Universidad Nacional Mayor San Marcos produced Vega Herrera’s evergreen work in 2014.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Mary Barnard.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.