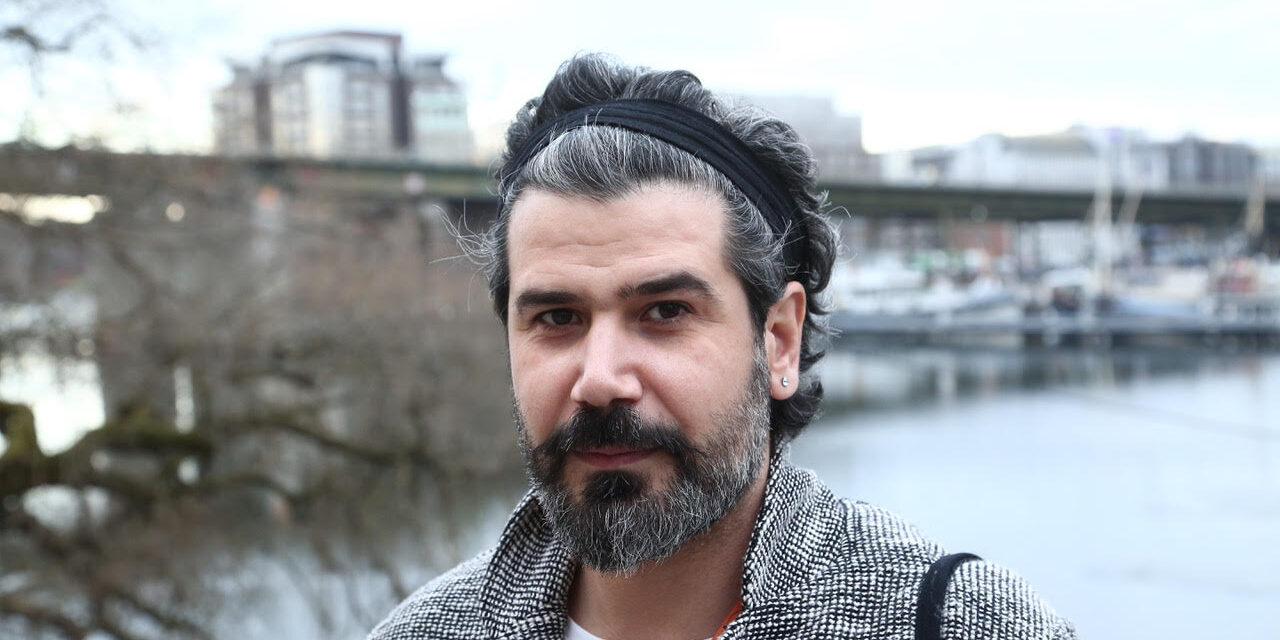

Ossama Halal is a Syrian theater director, choreographer, and actor. He started his artistic journey as a hip-hop dancer and trainer in 1994 until 2000. He graduated from the Acting Department of the Higher Institute of Dramatic Arts in Damascus in 2004. His artistic experience started while he was still a student as he founded the KOON Theater group in 2001 which participated in several workshops and artistic residencies: most notably Odin Theater in Copenhagen; Dream Think Speak and Grid Iron from Britain; Opus from France, and Teatri Del Vento from Sicily. Ossama was a choreographer and performer in the first three street and site-specific performances: On Your Way (2002), Bubble (2003), and Message (2003) which were based on body movement improvisation without text, and had been shown in Syria, Lebanon, and Denmark (Odin Theater). At that time he intended to present the performances toward the audience, not vice versa and consequently breaking the radical division created between the stage and theater viewers. This variant form did not yet exist in Syria whether at the level of performing techniques or that of place. His search for untraditional forms extended with later works despite moving to the Italian Box Set and dealing with text in performances: Tale of Aladdin (2005-2010), A Corpse on the Pavement (2006-2012), Station (2007), and Don Quixote (2008-2009) for which he was awarded “Best Director” at Cairo International Festival. After the physical performance Cellophane (2012-2013), he moved to Beirut where he established Theater Koon Lab, through which a series of workshops had been conducted for both amateurs and professionals living in Lebanon of all nationalities.

In Lebanon, Ossama continued his experimental theatre projects with the first physical performance Above Zero (2014) which was performed by Syrian and Lebanese performers. In collaboration with independent, diversely-skilled artists in his later performances Grand Voyage (2017-2018) and The Other Side of the Garden (2018-2020), (for which he was awarded “Best Performance” at the Cairo International Experimental Theater Festival), Ossama was able to pose various social and political questions through theatrical practices. For Ossama, theater is a practice in society that should not remain restricted to the elite, whether those graduates of the academies or other professionals. This vision formed the basis and principle of the Theatre KOON LAB as well, in which many workshops were organized and provided free of charge to the host community with a focus on writing, acting, dancing, music, and even lighting. Ossama also works on the idea of diversification and giving the performer the chance to experiment with different types of performing techniques by combining dancing, singing, and music with movement to create a new theatrical form.

The following interview took place by video call in Beirut on the 13th of February 2021.

Najwa Kondakji: It is known that you were a dancer before studying theater. Although time has passed I’m still curious, why were you heading towards acting not dancing?

Ossama Halal: I realized that there was no prospect for my career as a dancer. During the 1990s in Syria, two types of dance were practiced: folk or classical dancing (ballet) which were taught academically, but at that point, I have passed the appropriate age for attending. So, I’d have ended up as a dancer in a video clip or in a folk band, which doesn’t satisfy my ambition. What prompted me to theater was the inability of dance at that time to convey and express what I wanted to say, and many things have changed once I started my studies at the Institute.

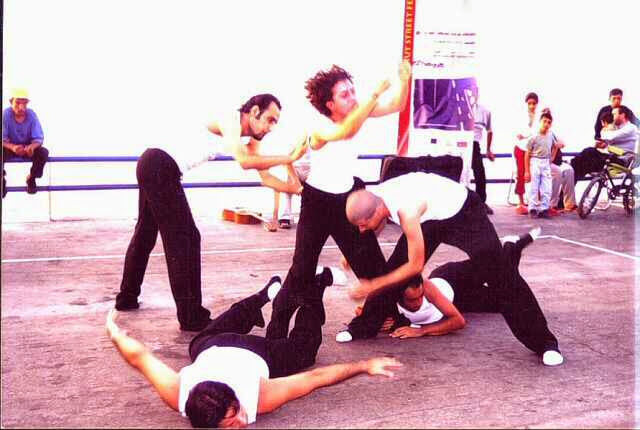

On Your Way– Physical Street Performance, 2002.

NK: Nevertheless, your first experiences started on the street, however this time not as a dancer, but as a movement trainer and performer. What factors drove you back to the street?

OH: Yes, when I started focusing on the kind of theatrical performances presented in Syria at that time (the end of the 1990s), I found out that all those works were driven within one mechanism. You could almost feel as if there was one director for all of them. This similarity appears all over the performance’s elements: acting, costumes, and the set-up where the script is the basis of the show and the director is just an executor of it. So in my approach to the street, I chose a radical path unlike the one that the directors usually followed. Moreover, due to a lack of financial means, I was able to avoid bureaucratic procedures that need approval from governmental institutions for text, submission, and budget.

NK: How was the working mechanism, or what was the starting point (fundamental ground) for the experimentation which you relied on to build the performance?

OH: I was working with my classmates and colleagues from other departments like Rami Farah from the dance department and Shady Ali from that of the music. I didn’t call myself a director but a choreographer because we didn’t have the right to be named directors due to some sort of censorship, and that’s a type of violence that we faced at that time. I thought of theater as a practice, not as a given theoretical material: it’s how to test ideas in a practical and creative way. Without the experimentation in theater, it won’t be possible for its theories to be grasped.

NK: After the street shows which you presented during your studies, you decided to move to the stage of Italian box, why?

OH: Yes, when I graduated, it became harder to work in the streets. As we live in a country that applies emergency law, I needed security approvals in order to present a street show, and I realized that I have to face superior institutions for decisions that I was unable to confront. Thus, I decided to go back to theater, with the experiences I have gained doing the street shows.

NK: How did the street experience influence your practice on stage?

OH: By dealing with the stage as an open space and creating an artistic structure uniquely at all levels of the performance’s elements and techniques. The performers can be seen at all times during the show, as there isn’t a closed backstage and the lights are kept on. This has allowed direct communication with the audience that rather meets with a Brechtian method to break down the fourth wall, despite the fact that the story of the show is not driven by an epic hero. It should be noted that I didn’t quite leave the street, and I came back to it in 2006 with A Corpse on the Pavement performance.

NK: Who has most inflected you among theatrical figures or scholars?

OH: At the beginning of my career, I relied on my own education. I didn’t even name my first works in “Physical Theater” as I wasn’t familiar with this term yet. Later during my studies, I found myself deeply influenced by Barba’s Odin Theatre, Grotowski, and the Oriental Theater as they provided me with answers to questions I have been concerned with for a long time.

NK: Can we say that there is a physical theater in Syria and that you are the one who started it?

OH: No, I wasn’t the only one. There was Nora Murad who is still working on physical theater, as well as Lawand Hajo’s experience with Muhammad Al Rashi which was pure dance.

The Other Side of the Garden– Physical Performance, 2018. Photo credit: Hubert Amiel.

NK: How do you see your experience within the theatrical scene at the moment, and how can it be distinguished from other ones?

OH: I’m just the first director to adopt extreme approaches when dealing with theatrical experimentation. Through exploring the relationship with the audience, I reached different classes of the society and I was able to go to places where theater could not have been performed.

Moreover, most of the artists were afraid of the form as if it would doom them in a way that the form cancels the content. For me, a new form can’t be created unless there is new content, it’s an interactive process. If this process does not approach profound internal questions, it cannot be reflected on the surface. In this context, I am only distinguished from others by my ability to experiment.

NK: Your experience started from body-based theater then moved to work on a script, have the artistic perspectives of your work changed accordingly in a way that focuses on the dramatic aspects rather than the physical ones? Or is influencing the viewer by breaking the traditional form your top priority?

OH: Why should we separate between movement and drama! All these definitions and classifications came from Western society, especially the European experience which strengthened this separation of acting, singing, and dancing. I believe that there are no borders between these types of performing arts. Arab theater has its roots in early fundamental experiences like the one of Abu Khalil Al – Qabbani who incorporated acting into singing and dancing that derived from social ceremonies and religious rituals such as Mawlawiyya; welcoming pilgrims with street cheers (Al Aradha); Mawlids, and wedding celebrations. By taking advantage of these tools, our own Arab theater might be created within its logical process, one should note that this process was interrupted by the religious and political authorities which were unwilling to reinforce the gatherings on the streets, and provided us with a specific set which seemed much like a container instead. In Syria, the concept of theater has turned into a building as a place of performance, which is far from the true meaning of theater itself.

Therefore, I don’t have a clear answer in my head because I didn’t decide what I was doing. My main concern was experimenting with all the performance components not just physical theater techniques, with a great ambition of mine to be identified as a theater maker.

NK: In spite of all the difficulties, you were able to establish the KOON Theater group in a country like Syria that does not have any tradition of civil society organizations. How could that happen? And what are the achievements of KOON from its establishment until the outset of the war?

OH: The institutionalization of groups was impossible in Syria. We were a group of mixed-gender young people working together and training in my house as it was the only option because civil gatherings were forbidden. The choice we were given was to work with one of the governmental bodies such as the Revolutionary Youth Union, the National Union of Syrian Students, or the municipality: all of which I could not work with.

When the Syrian revolution started in 2011, I found the answers to my questions: Why do I practice theater? Is theater necessary for the community? Can people live without theater? In this context, a very interesting thing had happened when the show A Corpse on the Pavement was re-presented after the outbreak of the revolution. The story of the show revolves around a beggar whose friend died of hypothermia, only for his corpse to be bought by a master to feed his hungry dog. When the show was presented in 2006, I was witness to many historic events: the fall of Baghdad; the assassination of al-Hariri, and the July War, back then I noticed the drastic transformation in the region where death was present. Although the political statements were terrifying, the Syrians did not pay attention to them at that time. On the contrary, the same spectacle shown in 2011 became an enormous source of risk that even my own friends accused me of insanity for displaying it, despite the fact that I didn’t change anything. People realized that the codes I was working on belonged to them and no one else’s. They became more aware of their community’s crisis as the political circumstance is reflected upon in our work reading.

In 2012, I worked on the dance show Cellophane because the censorship in Syria does not apply to dancing performances, and yet it was a political show. I found out that theater could be an artistic documentation for a particular event; a political stance; a witness, and a tool that meets with the concept of all Brecht’s and Saadallah Wannous’s plays. After this transformation, I left for Lebanon.

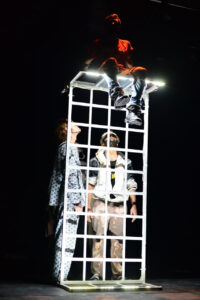

Cellophane– Physical Performance 2013. Photo credit: Mohamad Khayata

NK: But your departure was optional, and you were not obliged?

OH: Yes, it was my own decision because I could no longer practice theater in Syria. At the same time, the idea of “the permanent presence of death around me” became an unbearable stressful psychological factor.

NK: Was Lebanon a new beginning?

OH: A different one, but I was able to continue working as well. I was fortunate to attend distinguished shows of Lebanese artists such Roger Assaf, IssamBou Khaled with Fadi Abi Samra, Zoukak Theater Company, and other independent theatrical entities and artists. What I share with all of them is having a political perspective and an awareness of our community’s problems. At the same time, theaters are independent entities which means they are not monitored or subjected to any sort of accountability, Lebanon is a free cosmopolitan country where embassies are active and efficient and many artists come from abroad. Workshops and diverse artistic activities are held, with the presence of people of different nationalities. Indeed, working in Lebanon has influenced both my personality and artistic experience to a great extent. I founded a theater lab and rented a studio for it that was a dream for me.

NK: There is no doubt that the political structure in Lebanon (which is much different from Syria) must be reflected in the mechanisms of artistic production. This in turn brings difficulties of another kind: What are the main challenges? Do you consider that you were welcomed in Lebanon?

OH: It certainly wasn’t a romantic experience. No one would open their arms and invite you to the stage, my 8 performances in Syria were self-produced, and I am one of the few directors who did not receive a single funded production from any state institution. Currently, I fully rely on fundraising campaigns by some NGOs such as Al Mawred and AFAC.

The challenges are similar to those facing the theatre itself, sustainability is one concern: we get funding for one show, and then we have to wait another two years to get financial aid for an upcoming play. The performance is most likely to turn into a rehearsal.

NK: In addition to the fact that production mechanisms affect the artistic nature and its characteristics of the product

Above Zero Physical Performance, 2014. Photo Credit: Mohamad Khayata.

itself; you are addressing a different audience in this space of diaspora. Have your goals changed? Do you aspire to create a Syrian theatre or just a theatre as art? Is there a difference between the specificity of the artistic elements you’ve been working on and the existing ones in Beirut?

OH: This point has been recently the subject of many discussions among artists. There isn’t a Lebanese theater or a Syrian

theater. I don’t believe in these classifications. I’m just a Syrian director, practicing theatre. But if you mean to ask if the story of my shows tells a Syrian story, it doesn’t. It’s more human than Syrian. It’s true that the performances Above Zero and

Cellophane are apparently related to the uprising in Syria, but they’re also about violence, fear, and death. These questions concern everyone, and this tangible response I receive not only in Lebanon but in the perception of the people in Europe as well.

So, addressing a different audience, out of Syria, did not affect the content and the form. Of course, the specifications of the performance vocabulary have changed in comparison to the past, but they remained subordinate to the nature of the project itself and were not altered according to the different audience or space. I keep my basic goals that anyone is able to understand the language of the show and communicate with it, and by that, I don’t mean the spoken word, but the theatrical language.

NK: If it was possible to work in another place, would you go to?

OH: I got a job opportunity at a theater in Brussels and the Netherlands, and it was my decision to stay in Lebanon. It’s true that the freedom and the production opportunities are wider there, but the theater questions become different then. The meaning and the value of my job is here because what I care most about is reaching out to the audience.

NK: I think we cannot avoid talking about (COVID- 19) as we are all aware of its impact on the performing arts in general and on theater in particular. Are we facing a transformation in theater that will not be lost in the absence of the epidemic?

OH: I do not think so. Theater has lived through many transformations, disasters, and epidemics such as the plague, and it managed to survive since the audience’s relationship with the theater cannot be transformed. But what is dangerous, is that Corona forms a new kind of cultural colonialism, where the powerful countries impose a protocol on the poor ones, while our regimes have benefited from Corona circumstances to pass their political agendas. However, the role of theater or the mechanism of dealing with it, will not change after the pandemic.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Najwa Kondakji.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.