Ricardo Bartis (born in Buenos Aires, 1949), one of the major figures of Argentine theatre, took on the challenge of building a living theatre in the devastated cultural center that the dictatorship left. The experienced director created a generation of actors, including some of the best exponents of the current Argentine theatre. He created the Sportivo Teatral, located in the Palermo district. It is a real bastion of a theatre that comprises a sovereign place in its territory and that endures the hardships of consumption, “being categorized as a non-financial production.” In this interview, conducted at the Sportivo itself, Bartis makes reference to the external and own ideas about the director’s work from a critical and direct point of view. He also refers to the actor’s deciding role, the spectators’ place and his latest show, starring a bizarre cast of deceased actors.

La máquina idiota (“The Stupid Machine”) is the latest play directed by Ricardo Bartis, Buenos Aires.

The Director as the Generative Force of Stage Language

To Ricardo Bartis, the role of the director is essential to the process of production and articulation of theatre language. “’I’m not talking about THE director, but of a special one who is willing to create a language . . . from a linkage hypothesis between the strengths of the scene without giving him the possibility to tame them.” One of those central forces is the actor—who, in Bartis’ opinion, is almost like a shaman—then he goes on: “the vacuum is the play that is going to be formed from the scene where the heartbeat of the performance has to spread; it has to be an actor who can adapt quickly, who should be smart and able to follow the language and its complexity (not the play). The actor also strives to deliver a poetic event on stage and to make the audience (who consciously accompany the events) participate in it.”

Bartis also states that “the viewer is used to a comfortable site in a representational kind of theatre. The industrial system itself requires the separation of territories, of a sort of story where the bodies and their drive lose autonomy. A story where you cannot engage in discussion with the production system: I don’t like to watch a play from the 17th row of the official theatre. I like to see the actors’ sweat; I like a kind of theatre that has a more retiring perspective, that it’s addressed to a minority.” However, other theatres are more subject to the straitjacket of the character and to the psychological matter that tries to be as similar as it can to the current model—for which he proposes a new model: The director plays the role of the producer, who reduces the costs of production as window dressers do (you may be truly talented at it and earn a lot of money). Bartis stresses that into that specific model of the theatre world, “actors, acclaimed authors and directors have to pay a toll” because there is no place for aesthetic upheaval. “It’s something similar to manufacturing refrigerators (you’ll need them if you want to cool your champagne).” He finishes off his opinions by describing further experiences: “They’re moving us aside with this ‘post-dramatic’ side of the theatre, legacies from anemic cultures in which it is forbidden to think in a different manner. Our theatre is more vivid and I feel closely connected to the River Plate traditions.”

The Beginnings: Restoration in the Aftermath of Dictatorship

Bartis affirms that the military dictatorship created a void and the absence of linkages; “During the post-dictatorship era, new arenas spawned, bringing about new forms of communication and an innovative practice of stage direction, a different management of light, space, color, and staging devices. It created a vast new form of pedagogy.” Ricardo Bartis himself played a leading role in these changes. His play Postales Argentinas (1989) consolidated said transformation and became an iconic performance of Argentine theatre. Postales paved the way for new aesthetic and ideological possibilities that broke away from the standard guidelines of naturalism and realism, which were deeply rooted in Argentina’s theater scene.

La máquina idiota (“The Stupid Machine”) is the latest play directed by Ricardo Bartis, Buenos Aires.

Stage direction: Duties and Delegation

From his perspective, the delegation of direction duties to other trades implies risks, given that “as part of the creative work it is necessary to apply a horizontal approach in some areas and a vertical one in others.” In every rehearsal, the director

has the ultimate responsibility of bringing out the poetic personality of actors: that’s where new language must be created! If this is not accomplished, there’s no chance for the accrual of stage elements needed to navigate the narrative, which in turn entails underlying narrations and questions to be answered.

I direct all the time, in class, in here . . . whoever directs is the one who sees the space and has ideas, but must at the same time have a system of thought: a theatrical intelligence of sorts; not standard intelligence—otherwise any intelligent person, an intellectual for instance, could do theatre, yielding intricate results as we have seen. Theatre is a complex form of art, highly complex . . . if not it would be an activity for . . . well, it would involve an ingenious, banal way of conceiving direction.

The director of Sportivo also stated that, besides dealing with artistic concerns, the practice of direction is related to survival; with the way the director adjusts to the sets of rules and precepts associated with prestige that is stipulated by the cultural establishment—which often recurs to non-mainstream circuits for new outlooks to renew its own ideas.”

Towards New Work in Stage Direction

Bartis’ plays always raise great expectations. His next objective of theatrical exploration is violence: “I have some hypotheses on this theme; I have to sit down and analyze them, but I’m a little lazy, lacking will and enthusiasm . . . One must dive into things; there’s a sense of fundamental autonomy derived from movement, but it sometimes loses its strength—not the belief itself as much as the drive that gives momentum, but . . . it will come eventually . . . it will come. As time goes by, I feel more and more detached from words, I only believe in work . . . I think one needs to emphasize the ephemeral nature of theatre because that is where its powerful experience resides.”

The Dead and the Actor

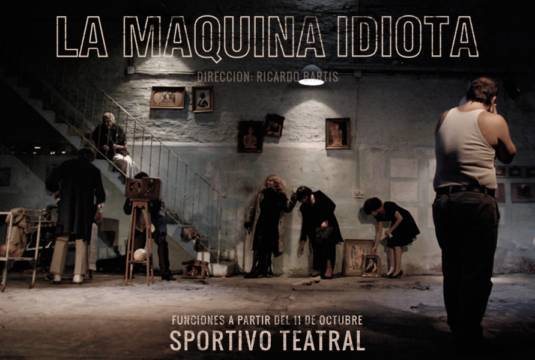

La máquina idiota (“The Stupid Machine”) is the latest play directed by Ricardo Bartis; the action is set in Buenos Aires, at Chacarita cemetery, which is adjacent to the official pantheon of the Argentine Actors Association. According to the play’s program, in that ghostly place growing “as if it were ivy, there has been a mutual society of minor show business personalities. In that place, a repeated and recurrent order directs them. Claims proliferate, and a rough melancholy full of suspicious memories and strained love affairs invades them. However, destiny has called them to stage once again: the union has called for the October celebrations,” and these bizarre actors frombeyond are trying to prepare for that occasion: Hamlet.

For several reasons, the choice of Shakespeare´s greatest work for this fiction essay does not surprise us: Bartis had already staged Hamlet by the early 1990s. He proposes an interesting new recycling of the text by integrating it into a larger project: a parodic and fragmentary insertion of a classic, juxtaposed with local quotes, sayings ,and speeches, some of which are of a mythical political origin and are always downplayed by humor.

Within the framework of La máquina idiota the director asks himself key questions that are of great importance: “Why are the dead and the actor the starting point in Hamlet?” They both are bearers of a truth. According to Bartis, the language of the dead “is the grounding element of politics.” (In the Argentine context, marked by the disappeared people under the military dictatorship, this “language” entails a special fate.) “The actor is and is not at the same time, which is inherent in acting. Hamlet is trapped in his heritage, and that heritage kills, corrupts . . .”

La máquina idiota (“The Stupid Machine”) is the latest play directed by Ricardo Bartis, Buenos Aires.

But what about the common heritage of the Argentine people? What about their myths and origins? “Argentina is always on the fence. We’ll see what happens, maybe we’ll get that fate of glory which has been cut off,” says Bartis. In La máquina idiota, an English character, who is frequently asked about Hamlet’s translation, spits out: “I should have suspected of a nation who sets up as a myth, a goal scored by a hand, and enjoys it!”1

Among his many successes, what the Sportivo’s director has achieved in this latest show is to emphasize the ephemeral nature of theatre plays by using the fact that the play involves its own birth and death. This is an axiom of the theatre that La máquina idiota deepens and repeats by displaying the acting power of the dead, as if it were “a strength that comes and demands.”*

To learn more about Richardo Bartis’La máquina idiota, visit Sportivo Teatral website.

*This interview was translated by Cátedra de Práctica Profesional. Traductorado Público. UMSA, Promoción 2015, Bs. As.

NOTES

- This refers to Maradona’s goal in the 1986 World Cup quarterfinal match against England, scored by the so-called “hand of God.”

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Halima Tahan Ferreyra.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.