From ancient tattooed skin to dental mouth gags, Unlimited’s latest collaboration with the Wellcome Collection sees Unlimited artists excavating themes of Work and Beauty through medical artifacts in the museum’s extensive collection. Natasha Sutton Williams spoke to the Wellcome Collection’s National Arts partnership manager David Cahill Roots about this research project.

“In its broadest sense, the Wellcome Collection is a free museum and library that aims to challenge how we think and feel about health, and the ways we can do that by bringing together different perspectives through science, medicine, life, and art,” says Cahill Roots. “Our aim is to blend different perspectives and different disciplines. Increasingly, what we’re trying to do is embed inclusion within that and embrace a range of different voices as well.”

This new focus has prompted the Wellcome Collection to invite disabled artists to reinterpret the museum’s extensive medical compendium, letting them loose to discover hidden stories lurking within the depths of the collection and archive. Through their findings, these artists are interrogating how disability is represented in the collection, and whether these stories relate to any of these artists’ personal lived experiences.

Deaf performance artist Chisato Minamimura has a particular interest in the visualisation of sound and music from the Deaf perspective and utilizes tech to share her experience of sensory perception and human encounters.

Using the Wellcome collection, Minamimura is exploring historical and contemporary representations of tattoos in both Western society and East Asian cultures.

“The starting point for my research is a tattoo taken from the Medicine Man gallery. I would like to find out about the history, culture, medical use and background of Irezumi (the Japanese word for tattoo).”

Theatre writer and performer Nye Russell Thompson is looking to bygone dental practices and artifacts to inspire his research.

“The objective from Wellcome to explore beauty inspired me to take stock of my own experiences. My research will look at societal standards of attractiveness through a lens of maxillofacial “differences,” like jaw misalignment, and deconstruct the stigma around them perpetuated through objectifying dental documents.”

Christopher Samuel is a multi-disciplinary artist whose practice is rooted in identity and disability politics. Seeking to cross-examine his personal understanding of identity, through the collection Samuel is “investigating the historical difference and similarities in the challenges faced by disabled people, from the context of my own experience. I will be examining how the material collected in Wellcome Collection does or does not reflect my own lived experience, how my experience is represented in the collection, and how this is mediated over time.”

Racial types and people with physical abnormalities exhibited at S. Watson’s American Museum of Living Curiosities. PC: The Wellcome Collection.

Historically, over the last 70 years, the Wellcome Collection has been viewed as an academic and medical resource. However, in the last 10 years, artists and creatives have adopted this massive archive of unique, bizarre, and extraordinary resources.

“This work fits into the bigger idea of how we support a wider range of folks to access the collection, to interrogate it, and to challenge it,” states Cahill Roots. “It’s an active collection where we’re continuing to collect perspectives on health and what it means to be human right now. This wider range of collaborators helps us as an organization to think about what needs to be displayed in the collection in the future.”

Stemming from this concept to gather new perspectives on the collection, visual artist Kristina Veasey is one of the artists mining the archive for artistic jewels. Her work concentrates on flipping negatives into positives and finding beauty in the mundane. Veasey has experienced the collection as

“a treasure chest full of historic gems, with each item providing a little snapshot of a time past. There’s so much material that a lot of it hasn’t really been given much attention. Exploring the archives is like hunting for clues. Even seemingly mundane items can be revelatory; there are some pretty weird and wonderful things in there.”

Writer and actor Sophie Woolley works across theatre, TV, radio, and literature. Using the archive, Woolley is researching the roles of Deaf women in film and TV. Her research project ‘And What Do You Do?’ asks historical Deaf and disabled people in the collection what they did for work, and whether it is even documented. Wooley states that the archive reveals

“hidden windows into old worlds and opens doorways onto surprising new understandings of why our lives are like they are today. How do the past documentation and work prospects of deaf/disabled people inform today’s culture, in particular television drama?”

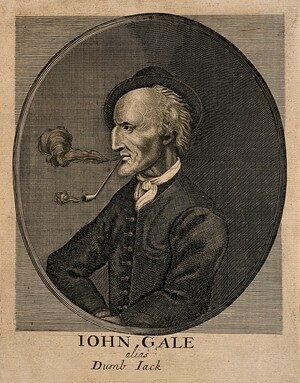

John Gale, known as Dumb Jack, a deaf mute. PC: The Wellcome Collection.

It can be argued that the Wellcome Collection has previously adopted the traditional medical model of disability instead of the more nuanced and modern social model of disability. But things are changing.

“It is apparent through conversations I’ve been having with the artists – which isn’t at all surprising – that there is a pressing question of identity. Where do they see themselves or some aspect of themselves within the collection? In its deepest history, the Wellcome is a kind of medical collection; it takes a certain view of bodies and people as subjects. The question of identity and where is the individual’s voice rather than the medical voice is what we are exploring with the Unlimited artists. Our newest permanent exhibition Being Human really tries to center on the social model of disability, and what that means for our practice as an organization.”

Cahill Roots adds:

“With this latest research project we’ve asked the artists to think about beauty, work, and how we can bring a critical perspective to the historical approaches to collecting within the working collection. There are Wellcome employees who are also thinking about these elements, have done research into the collections, and were able to offer provocations for the artists. These colleagues have been able to check in with the artists to see what they’re thinking, and have been able to reflect and take on board some of the artists’ approaches to those ideas.”

To dig into the depths of the Wellcome Collection for yourself, please see the Wellcome Collection’s website: https://wellcomecollection.org/

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Natasha Sutton Williams.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.