Ballroom culture is quietly flourishing in China’s cities, creating a safe space for young LGBT people to explore their identities.

SHANGHAI — When he’s hanging around campus, Zhao Zixun often blends into the background. A pimply 19-year-old with a neat buzz cut, he usually dresses simply in baggy pants and tattered sneakers.

But on a Saturday night in early December, Zhao transforms into an exuberant, stiletto-heeled diva.

The student has entered Millennium Storm — one of the Chinese mainland’s first voguing balls, hosted in a packed two-story venue in downtown Shanghai.

The ballroom scene — a subculture where performers compete in extravagant dancing, lip-synching, and modeling contests — is quietly starting to take off in China’s major cities, creating a space for LGBT millennials like Zhao to cut loose and explore their identities safe from the prying eyes of more conservative friends, relatives, and classmates.

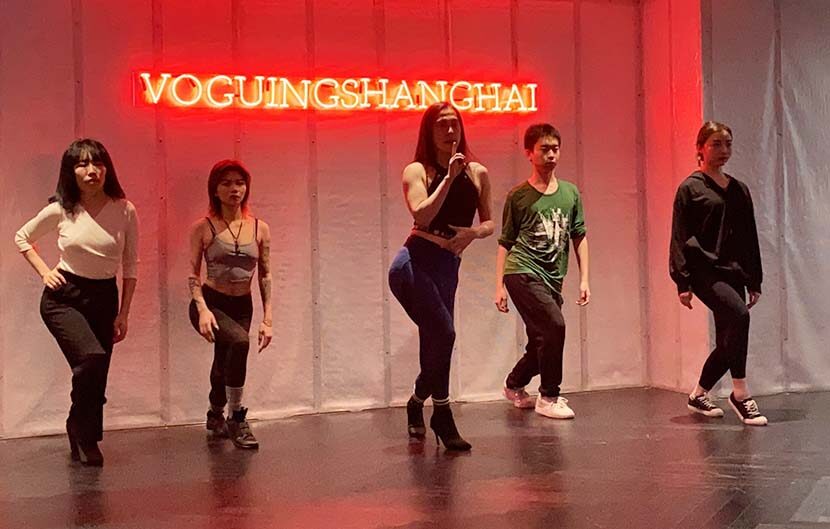

Contestants perform at the Millennium Storm voguing ball in Shanghai, Dec. 5, 2020. Wang Xuandi for Sixth Tone

The Shanghai contest has attracted an eclectic mix of entrants — from elegant drag queens in body-hugging qipao dresses, to stout men in fishnet stockings. They shake and flex on the brightly lit runway, competing for the crowd’s approval.

Zhao, who’s wearing a black jacket and pants with matching heels, initially worries his outfit is too plain. But when it’s his turn to head onstage, he draws waves of cheers from the several hundred spectators, who respond to the contrast between his immature looks and dashing poses.

This is Zhao’s first time performing at a ball, and the normally shy and withdrawn sophomore is in his element. As he performs, he moves in an improvised duet with the emcee freestyling over the pounding house beat. After some flowy, sensuous movements, Zhao stalks the stage, kicking his feet up high, then slowly dips toward the ground as if he’s melting.

“I just feel at ease with these voguers,” Zhao tells Sixth Tone after the show. “I no longer need to emulate masculinity as I often do when I’m outside. I don’t need to put on a disguise.”

Originally from the central Henan province, Zhao grew up in a conservative family. Though he identifies as gay, he has yet to come out to his parents or his friends at college. He keeps his high-heeled shoes hidden in his closet in the student dorm.

But Zhao has found freedom in the secret classes he has been taking this year at Voguing Shanghai — one of a small, but growing number of Chinese studios teaching the highly stylized house dance known as voguing.

Voguing first emerged among New York’s Black and Latino communities in the second half of the 20th century, gaining mainstream exposure thanks to Madonna’s 1990 hit song “Vogue” and the documentary “Paris Is Burning,” released the same year.

From the beginning, the subculture played an important role in American LGBT communities, with voguers forming “houses” that functioned as de facto families for the group. Leaders of the houses would be referred to as “father” and “mother” and would provide shelter and guidance to their “children” — often LGBT youth who had been abandoned by their families due to their sexual identities.

Voguing culture has since gone global, but it only gained traction on the Chinese mainland after 2014, when Irina Bashuk — a member of the legendary House of Milan — fled to China from her native Ukraine, which was then descending into conflict.

At first, Bashuk struggled to get Chinese dance studios interested in voguing, but by 2016 she was teaching regular classes in Shanghai, attracting a group of loyal followers who would go on to form the backbone of the city’s ballroom scene.

“Regardless of our differences in language, mentality, and lives in general, people’s lives change when they start voguing,” Bashuk tells Sixth Tone.

In 2018, Bashuk founded China’s first voguing house: the Kiki House of Kawakubo in Shanghai. She left China shortly after, but the country’s subculture has continued to grow in her absence.

There are now three voguing houses on the Chinese mainland, while Voguing Shanghai — a platform for organizing and promoting dance classes and balls — was founded in 2019. The body also opened its own studio in Shanghai’s former French Concession in April.

Like their American forebears, the Chinese houses provide their mostly LGBT members with an important support network. Chinese society has gradually become more tolerant toward sexual minorities over recent years and it has become rarer for families to shun children after they come out, but LGBT people still often find themselves isolated and misunderstood.

“The voguing community is a type of society where people know it’s OK to be themselves,” says Li “Bazi” Yifan, the father of the Kiki House of Kawakubo. “It’s safe for them to show up and be respected.”

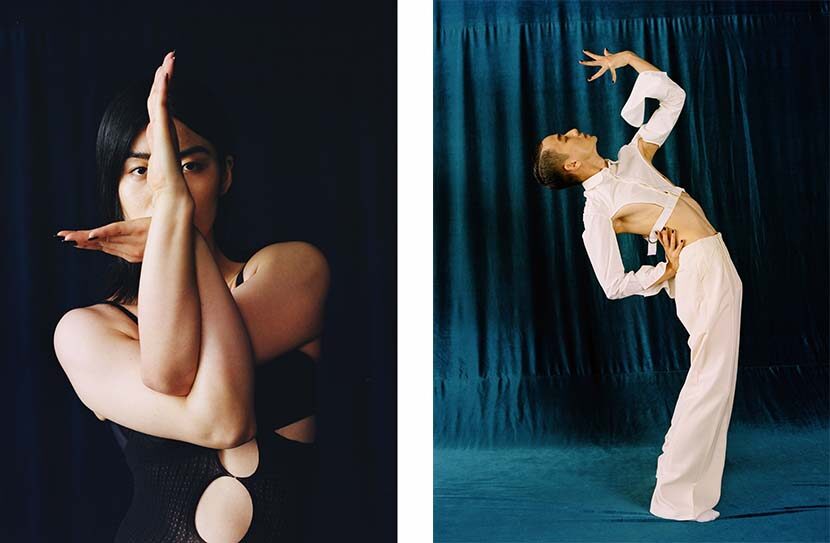

Left: Zhou Xuelian, mother of the Kiki House of Kawakubo; right: Li Yifan, father of the voguing house in Shanghai. Courtesy of Zhou Xuelian and Li Yifan.

One of the first members to join the Kiki House of Kawakubo was Zhang Weijie, who now goes by his stage name of VJ. He tells Sixth Tone that voguing has changed his life.

Like Zhao, the student, Zhang is from a socially conservative family. Growing up in a village in the eastern Zhejiang province, he wasn’t able to grow his hair more than an inch long, otherwise, his father would give him a beating, he says.

Zhang cameChina out as pansexual while he was in high school, but his parents reacted negatively. This experience, combined with his parents’ unhappy marriage, left him with lasting emotional scars. For years, he bounced from job to job, and from city to city, eventually becoming a programmer in the southern city of Zhuhai.

But learning to vogue has helped the 27-year-old find himself. He first joined Bashuk’s classes in 2016, traveling over 1,500 kilometers from China’s southern coast to Shanghai. It was worth the effort: The expressive choreography and dance moves — as well as the community’s kind, positive atmosphere — immediately appealed to him, he says.

“I used to feel like I was floating,” says Zhang. “But now I meet people I know so well, and I know they’ve got my back. I no longer feel lonely.”

Voguing has also helped Zhang finally feel comfortable in his slender, wide-hipped body, he says. He now works as an instructor at Voguing Shanghai, where he prefers to dance in a tight jumpsuit and 9-centimeter heels, to show off his figure.

“VJ has come a long way, from an IT office worker to a beautiful artist, and he’s still continuing the search for his true self,” says Bashuk. “That’s how dance, art, unity can change a person.”

With voguing now well established in China, the movement is working to take the next step: winning mainstream acceptance for the country’s fledgling ballroom scene.

Though LGBT events can run into trouble in China, balls haven’t encountered any problems so far, with Voguing Shanghai careful not to explicitly promote them as for the queer community. The group is helped in this by the fact that balls also attract a large number of cisgender women.

After testing the water with a small event in July, Voguing Shanghai went big with Millennium Storm — the show serving as a coming out party of sorts for the subculture. Entrants competed in six categories: best-dressed spectator, runway, hands vs. arms, butch queen realness, virgin vogue, and vogue OTA (open to all).

Li, the voguing house father, who helped organize both events, says the balls are designed not only to be a celebration for voguing insiders, but also to attract publicity and win new converts. “(In July’s ball,) we set up the runway (contest) mainly to attract people in the fashion industry,” he says.

The voguers are already generating a buzz. Several members of the Kiki House of Kawakubo have been profiled in Chinese media and appeared in advertising campaigns for brands including Nike and Converse.

Voguing’s growing commercialization, however, is generating tension within the movement. Though house members like Zhang are often LGBT millennials from humble backgrounds, many feel voguing in China is becoming increasingly “bougie” as dance classes become a fashionable lifestyle activity.

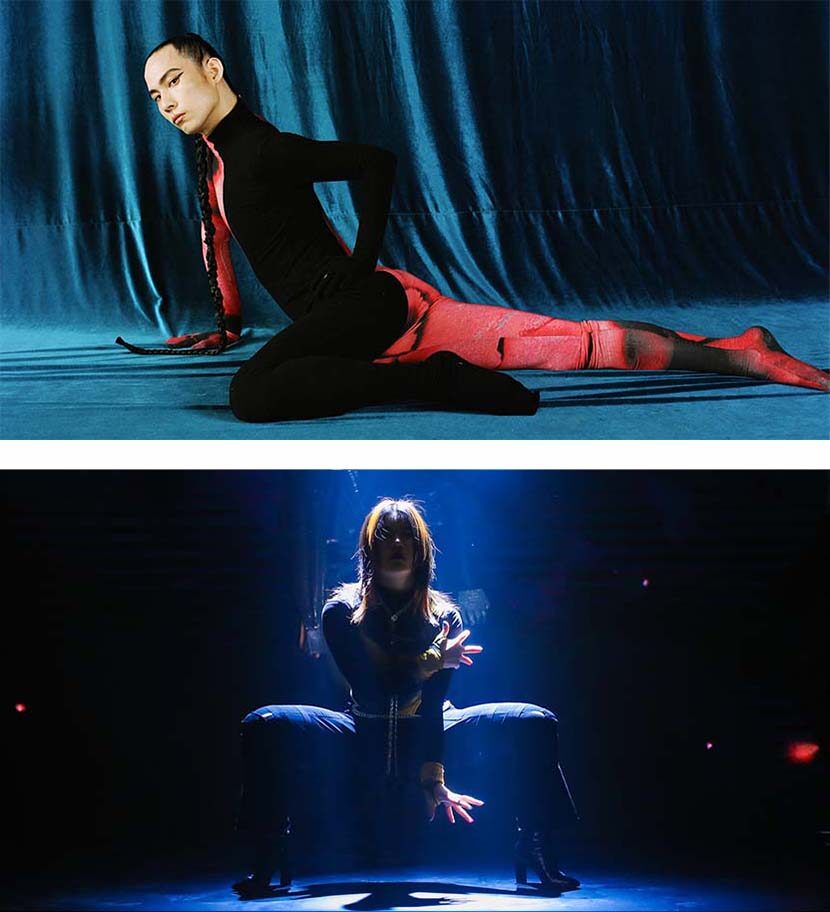

Above: Zhang Weijie, also known as VJ, poses for a photo; below: Zhou Xuelian performs at a voguing event in Shanghai. Courtesy of Zhang Weijie and Zhou Xuelian

Millennium Storm only added to this impression, with some voguers dismissing the ball as “extravagant and pompous,” Li confesses.

“We can attract the attention of investors and the fashion crowd and cooperate with leading brands,” he says. “But at the same time, there’s a feeling that walls have been erected, making it less likely that China’s less privileged sexual minorities will be able to join our community.”

Another source of strain is the fact that — unlike in the U.S. and Europe, where ballroom culture tends to primarily attract trans women and gay men — voguing has become popular among cisgender Chinese women.

In China, where policing of gender identities is pervasive, queer-exclusive spaces are particularly valuable for allowing LGBT people to experiment with their gender performance, according to Tan Chenyu, a doctorate candidate at London’s Royal Central School of Speech and Drama whose research focuses on queer culture in Shanghai.

“For disenfranchised LGBT people, the ability to change yourself by shaping your looks and movements may be one of the few options to assert power,” says Tan.

Yet Zhou Xuelian, the mother of the Kiki House of Kawakubo, is adamant that Chinese women and LGBT groups can coexist harmoniously. “They’re both subject to a lot of repression,” she says. “Voguing allows women to find a release, too.”

Zhou, who is cisgender herself, has personally shown how women can make big contributions to the voguing community. Since signing up for classes with Bashuk in 2016, the 27-year-old has become one of the most prominent voguers in China.

In 2018, she became the first person from the Chinese mainland to join the House of Milan, winning herself the name Shirley Milan. Now, Zhou says the voguing scene’s move into the mainstream is inevitable.

“I’ve always felt that voguing itself shouldn’t be a minority culture,” Zhou says. “There are too many restrictions on women in Chinese society … but voguing encourages them to be themselves and be more confident.”

Zhao, the sophomore, meanwhile, has been energized by performing at his first ball, even though he didn’t make it past the second round this time. He says he’s determined to keep voguing, and hopes he’ll one day be good enough to join the Kiki House of Kawakubo.

For now, though, Zhao says he’s going to keep his high-heeled shoes hidden from his dormmates. “Maybe in the future I’ll gradually come out to them,” he says.

Contributions: Qin Siqi; editor: Dominic Morgan.

This article originally appeared on SixthTone.com on December 17, 2020, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Wang Xuandi and Fan Yiying.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.