The recent release of the musical Hamilton by the Disney+ channel on July 3 received favorable reviews across Canada and the United States.

Critics have lauded the musical for its innovative mash-up of “hip hop, jazz, blues, rap, R&B, and Broadway” and for how the show jubilantly demonstrates hip hop’s entwinement with American traditional ideals of self-invention and freedom.

The musical has also been praised for casting mostly “Black and brown faces” in roles of the American Founding Fathers, a move that underscored how political ideals in the United States belong to and are creatively advanced by all Americans.

What is especially interesting in the summer of 2020 is that Hamilton was presented at a time of intense political divisiveness and protest in the U.S. The streaming of Hamilton also gained dramatic significance in the context of the recent Black Lives Matter protests in face of racist police violence.

Many have interpreted the July 3 release, one day before American Independence Day, as intended to remind patriotic Americans of their ability to unite and work towards a fairer government and society.

Puzzled historians

Ever since the musical was originally staged in 2015, many professional historians were surprised that a musical about statesman and Founding Father Alexander Hamilton, mostly known for having his portrait on the 10-dollar bill, would be such a commercial and critical success.

Given Hamilton’s interest in challenging traditional narratives, demonstrated both by show’s largely Black and racialized cast and brilliant appropriation of diverse musical and theatrical traditions, some historians of the American Revolution have been puzzled that the show didn’t explicitly address how the white historical figures were connected to the history of slavery and anti-Black racism.

Although the show’s creator and star Lin-Manuel Miranda portrayed Hamilton as a man dedicated to the abolition of slavery, historians like Annette Gordon-Reed have argued that Hamilton was only moderately concerned about eradicating the institution of slavery in the U.S.

For Hamilton, ensuring the survival of the U.S. as a nation-state trumped any other concerns, including slavery. This meant making awkward compromises with the Southern slave-holding states.

Indigenous Peoples and Lands

Neither the musical nor most historians have addressed how Hamilton’s political ideas affected Indigenous Peoples. Hamilton was not as directly involved in diplomatic negotiations with Indigenous nations, unlike President George Washington.

However, Indigenous Peoples cannot be separated from the story of the founding of the U.S. This claim is most recently put forth in a study suggesting Indigenous history is central to all U.S. history. This is particularly true for the first decade following the end of the American War of Independence.

After Britain had surrendered its claims to North America, with the exception of Canada, to the U.S. in 1783, a number of powerful Indigenous nations still occupied lands west of the Appalachians. These nations included the Cherokees and the Creeks in the Southeast as well as a confederacy of nations consisting of Shawnees, Wyandots, Lenapes (Delawares), Ojibwes, Ottawas, and others in the Ohio region, known as the “United Indian Nations.”

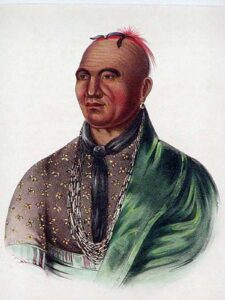

1830s lithograph of Mohawk leader Joseph Brant, based on the last 1806 based on oil portrait by Ezra Ames. (Wikimedia Commons)

Joseph Brant (Thayendanegea), the Mohawk leader who had been closely aligned with Britain since before the American Revolution, was one of the initiators of the United Indian Nations in September 1783. There was a constant fear among U.S. politicians that these Indigenous nations would align with Britain and Spain against the United States.

Federal Military Force

As historians Gregory Lablavsky and Jeffrey Ostler have shown, Hamilton advocated for a federal military force that would be able to confront “the savage tribes on our Western frontier [who] ought to be regarded as our natural enemies” during the constitutional ratification debate in 1788.

According to Hamilton, the Indigenous nations in the west would support the Spanish in Florida and the British in the Great Lakes region “because they have most to fear from us and most to hope from them.”

In Hamilton’s opinion, a strong national army was necessary to deal with the European and Indigenous threats to the new nation. Once the U.S. Constitution was ratified in 1788 with its emphasis on a strong central government, Hamilton became the first Secretary of the Treasury in 1789.

Leveraged taxes for genocidal warfare

In that role, Hamilton ensured that the American government had an army at its disposal that could be deployed to wage genocidal warfare against Indigenous nations.

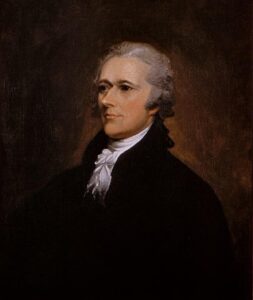

Portrait of Alexander Hamilton portrait, about 1805, by John Trumbull. (Wikimedia: Smithsonian Art Inventory Catalog, IAP 08930129)

In June 1790, Brig.-Gen. Josiah Harmar, the commander in charge of the U.S. military efforts against the United Indian Nations in the Ohio region, received instructions from Secretary of War Henry Knox to go on the offensive, “to extirpate, utterly, if possible, the said Banditti.” This was a demeaning reference to the Indigenous warriors who were defending their lands and families.

The verb extirpate was used in the 18th century as synonymous with exterminate.

Although the Indigenous confederacy was able to hold back the U.S. Army for several years, the American military wore down the confederacy by 1794 by repeatedly destroying Indigenous villages and cornfields. The actions of the army forced Indigenous Peoples to surrender the fertile Ohio Valley to the U.S. in 1795.

Joseph Brant and his followers, mostly Mohawks and other members of the Haudenosaunee or Six Nations confederacy, escaped American expansion by resettling on the Grand River in Upper Canada. However, Brant and the Haudenosaunee soon became embroiled in complex negotiations with British officials over the meaning of the Haldimand Proclamation of October 1784 that originally created the huge tract of land for the Six Nations along the Grand River.

The Shawnees, Wyandots, and Delawares continued to defend their lands against the United States until the end of the War of 1812. After 1815, many members of the United Indian Nations migrated to Missouri and Kansas to escape American expansion. During the 1830s, the remaining Indigenous Peoples in Ohio and Indiana were forcibly removed by the U.S. government to reserves in the Indian Territory (now Oklahoma and Kansas). Their descendants still live there today.

Fateful Consequences

Clearly, Hamilton’s ideas of a federal army and an expanding nation had fateful consequences for the Indigenous Peoples who lived in what is now Ohio and Indiana.

Just like the musical could have dealt more fully with slavery, the inclusion of Indigenous perspectives would have forced audiences to grapple with the implications of Hamilton’s policies.

For all its brilliant creativity, the musical missed out on the unique opportunity to inform the public about the impact of the new American nation upon the Indigenous nations of North America. Perhaps, one day, a new musical will be written about the origins of the U.S. that explicitly incorporates Indigenous perspectives and actors.

This article was originally posted at theconversation.com/ and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Mark Meuwese.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.