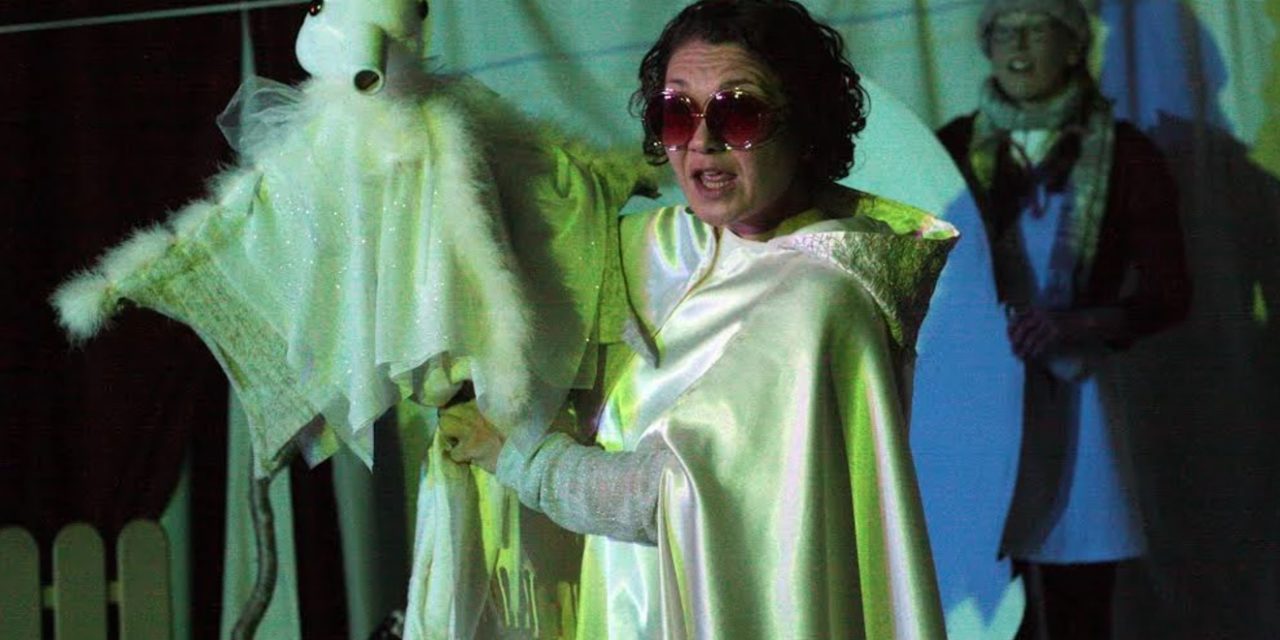

National Eisteddfod. Courtesy of Wales Online.

Summer. If you’re a Briton, it’s the lasting struggle and hope for sunshine. Nonetheless, theatre festivals continue to hit our fields, meadows, cities, towns and beyond. Latitude will grace Henham Park in Suffolk during July. Open-air theatres up and down the country will flood the parks to put on a season of productions. In fact, the UK leads in the long-standing tradition of outdoor productions of Shakespeare’s works. Perhaps more widely-acclaimed is the annual Edinburgh Fringe Festival, which celebrates its 70th anniversary as it prepares for its take-over of the city.

Wales is trimming the grass for its share of festivities too. We embrace all weathers, mostly bad and we’re rolling out the tents and pitching the pavilions this year like every other. A ‘gwyl’ (which in Welsh simply means ‘festival’) is as much a part of our theatre culture as any other country. For this article, I’d like to address two festivals in particular. Purposefully, both are on opposite ends of the timeline. One which has walked, talked and long left the nest and the other still nestled in its mother’s arms, waiting to explore.

The National Eisteddfod of Wales is a celebration in the preservation of the Welsh language through its varied art forms. Although we have a wide selection of Wales’ finest gracing its stages, it’s the competitive elements that make this festival different. Each year, the Eisteddfod (and its sister counterpart the Urdd Eisteddfod (youth)) have thousands competing for its prizes in drama, music, fine art and dance.

Last year, the Eisteddfod visited the town of Abergavenny, a small rural town in the South of Wales. Being so close to my own hometown, I ventured there every day for the seven-day festival to experience what was on offer. I had never anticipated how much theatre thrives in this language. So much so, we can call this our leading theatre festival for the Welsh-language.

This year, new work will be presented by the flagship theatre company of Welsh language Theatr Genedlaethol Cymru (Wales’ Welsh language national theatre) in the form of two productions; Hollti by Manon Wyn Williams, a verbatim piece on the construction of the new Wylfa nuclear power station in 2026. The second, Estron is a new play from the winner of the medal for drama in 2016, Hefin Robinson. Productions such as Robinsons’ ensure the commitment of Theatr Genedlathol Cymru’s commitment to producing and nurturing new writers and their work. The Eisteddfod is a more than ample beginning for a Welsh-language playwright. Elsewhere, across the ‘drama village’, new work will be presented from many of Wales’ theatre companies and institutions including the Sherman Theatre, Dirty Protest, Theatr Bara Caws, Spectacle and Pontio throughout the week, proving that Eisteddfod can bound its theatre’s together in a celebration of the work the Welsh-language feeds us as a nation and beyond.

When will more be introduced? Hopefully, in the next few years, we’ll see a platform for Wales’ first pub theatre The Other Room, or maybe a slot for Theatr Clwyd. There are endless possibilities.

The Eisteddfod thrives on the communion of Welsh-language art coming together. Yet, the Eisteddfod still only attracts a much higher percentage of Welsh-speakers. Many speculations have been discussed on how it may make itself more accessible to a wider public. A threat was made to the funding of the festival following the 2010 pavilion in Ebbw Vale, a small ex-mining town in the South Wales valley, stating that unless the festival modernised its roots it would be in danger of falling behind. Since, the festival has done just that, resulting in a more relaxed and embracing the works of more contemporary themes and ideas in the works it produces through the innovation of modern theatre companies such as the Sherman Theatre (a house for new writing based in Cardiff) and Dirty Protest, who thrive on the development of exciting and fresh new voices in both the Welsh and English language. But, like the ever-changing world, it’s evolving and the Eisteddfod is another cog in the clock that must keep turning.

I’m positive. In fact, I’m excited.

The second festival I’d like to talk about will be a fresh initiative. For the second year running, Cardiff will play host to its very own fringe festival. The aptly named Cardiff Fringe Festival is an exciting new initiative for Wales’ capital city and the first of its kind.

Courtesy of ‘Cardiff Fringe Theatre Festival’

Whilst the programme is still finding its feet, last year’s successes have proved that it’s progressive. This year alone, many of Wales’ aspiring companies are making their way to its stages. Venues such Chapter Arts Centre and The Other Room are offering their names and spaces for work to be produced. With its revealed youthful spirit, the fringe has promised some exciting works across the city. Furthermore, their offerings of various from casting, to writing and director from the likes of Dan Jones (Artistic Director of ‘The Other Room’) and Nicola Reynolds (casting) have proved that not only does the fringe have room for presentation but for the development of artists too. As the years come, I have no doubt that the fringe will stretch over the borders and invite even more companies into our bread of heaven to revel in Wales’ theatrical landscape.

There are legs left to climb the ladder, but we’re all climbing the ladder behind too. The only way to go? Up.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Christopher Harris.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.