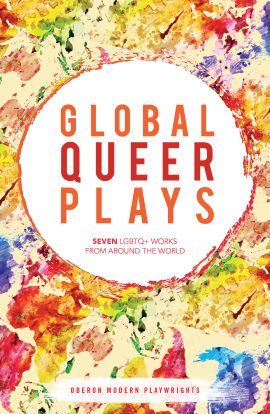

Global Queer Plays, published December 10, is a unique anthology bringing together stories of queer life from international playwrights. These seven plays showcase the dazzling multiplicity of queer narratives across the globe: the absurd, the challenging, and the joyful. Here, Jeremy Tiang, the translator of Taste Of Love, and Danish Sheikh, writer of Contempt, talk us through the process of working on their plays, what it was like to watch the Arcola Queer Collective staged readings, and more.

Jeremy Tiang

Jeremy, how did you come to translate Zhan Jie’s play?

I find a lot of the work I translate through recommendations—particularly with plays, which are often unpublished. I’d just translated Wei Yu-Chia’s A Fable For Now (which has since had readings at PEN World Voices in New York and Yellow Earth/Rich Mix in London), and I asked her if she could suggest some other Taiwanese work I should take a look at. She sent me Zhan Jie’s play, and I loved it.

Danish, could you talk about the origins of the play you wrote?

In 2013, the Supreme Court of India upheld Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, effectively sanctioning the criminalization of the intimate lives of LGBT persons. The judges held that we constituted a minuscule minority and were thus undeserving of constitutional rights. These words stung me at multiple levels: as a practicing human rights lawyer, a member of the litigation team that had fought the case and lost, a vocal queer rights activist, and a gay man.

I knew that the legal battle would proceed and that LGBT Indians would continue to live their lives, but I needed to find a way to transmute the anger I was feeling into something resembling hope. I needed to dissent. I’d done some theatre work before, but never something approaching a full play. It was under the guidance of Neel Chaudhari and the Tadpole Repertory, at a summer workshop on playwrighting in Delhi, that I picked up the skills and confidence to write a piece that I imagined almost as a direct challenge to the law.

Contempt began as a theatrical rendition of the Supreme Court hearings in the 377 case. I then placed excerpts from thousands of pages of Court transcripts alongside the stories of LGBT Indians that did not make it into the courtroom. I hoped to show the ways in which the Court used a distressingly narrow reading of the law and was unable to engage or account for the narratives of queer persons.

What was the reason for you submitting this play to the Arcola Queer Collective’s call-out?

Jeremy: I was very excited to hear of the call-out—I’m queer, and I’m a translator, but how often do I get to be a queer translator?—and knew right away that this script was the one most likely to resonate with a British audience. There’s something about the claustrophobia of the school setting and the challenges of dealing with “difficult” students that I thought felt universal.

Danish: I was interested in seeing how the work would resonate outside the Indian context–and what better place to test this out than the country which gave us the anti-sodomy law to begin with? There’s many points in the play at which the colonial origins of the law are referenced and the idea of imagining it enacted in London of all places was tantalizing. I was also curious to see what somebody outside the Indian context would make of the play in terms of interpreting the text on stage.

What did you think of the experience of seeing the staged readings, and what do you think of the plays being published?

Jeremy: The readings were GREAT. It was a thrill to see Taste Of Love brought to life by a fine cast and director, but more than that, the plays collectively became larger than the sum of their parts. This festival was a powerful statement: look at all the voices being raised around the world, highlighting different challenges in different cultures, but all speaking of our shared humanity.

Danish: It was revelatory. Back when I’d performed the play in India, I’d worked a lot with technical elements–using sound, light, stage design to bring out the text. The Arcola reading took away all the bells and whistles and focused purely on text and performance. I was delighted and moved by many of Tasmine Airey’s directorial choices here: the play seemed to acquire a more raw energy and a heightened sense of pacing.

What was also enjoyable was watching Jeton Neziraj’s absolute romp of a satire, 55 Shades Of Gay, immediately after: the manic levity of his play was a perfect contrast to the weightiness of mine. The fact that the play is seeing the light of day in a published book is huge for me–it’s very difficult to get plays published in India. To then have these plays part of a global conversation in an anthology that includes narratives from places like Taiwan, Jordan, and Argentina is incredible.

Both India and Taiwan have made some significant moves towards legislating for queer rights in recent years (though of course, social attitudes will take longer to shift). How do you think this will affect queer artists and writers, and the work they do, in the future?

Jeremy: I’m hoping this means more queer artists and writers will feel able to come out of the closet, should they want to, which I think can only lead to better art—people being their authentic selves have more energy and clarity for the work. That said, the recent Taiwan local elections were a disappointment on this front, so it’s clear the struggle will continue for some time to come—but at least there are bright spots.

Danish: A lot of the queer theatre in India that I have observed can be read as a dissent to the narrative of criminalization. This isn’t necessarily the creator’s intent of course, but the themes that are tackled often foreground the importance of expressing queer identity in a particular way, and make it central to the narrative. This has been immensely important, of course, given the specific way in which theatre provided a space for conceptions of justice that the law would not allow.

I wonder if with decriminalization and other positive shifts in the law, we might have narratives where queerness is a launching point for asking other questions. This is not to say that queer identity and its expression be rendered irrelevant, but rather that we’re able to look at themes that go beyond accounts such as coming-out, navigating sexual identity, state atrocity, to name some of the common tropes.

What are you working on now?

Jeremy: I’ve translated plays by Chen Si’an and Zhang Zai which are being workshopped at the Royal Court, so I’m part of that development process. I’m also translating a novel by Lo Yi-Chin, Far Away, and—more Taiwanese queerness! — slowly working my way through a collection of gay short stories by Hsu Yu-Chen, Purple Blossoms. Plus some writing of my own, but I’m superstitious and won’t talk about that till it’s done.

Danish: I’m writing a direct follow up to Contempt, this one taking off from the Supreme Court’s recent landmark decision decriminalizing queer intimacy. Going with my response to the previous question, I’m trying to explore themes that are distinct from those in Contempt. The central idea in Love And Reparation (which is what the play is provisionally titled) revolves around how we construct narratives, in law and love, and difficulty of actually holding on to that kind of structured narrative as we live our lives, whether it comes to questions of legal change or how we think about love.

Are there any works by queer writers or artists that you’ve seen or read recently that you’ve loved?

Jeremy: I just saw Slave Play by Jeremy O. Harris, directed by Robert O’Hara, and it was one of the most intriguing pieces I’ve experienced in a while. It begins, provocatively, by looking at slavery through the lens of S&M, then layers on the other ways in which race and sex can intersect. There was a lightness to the play that I appreciated–it asked important questions, but never allowed itself to get bogged down by their seriousness.

Danish: So many! I’ve greatly enjoyed going through the other plays in the Global Queer Voices anthology. I recently came across the play Gross Indecency: The Three Trials Of Oscar Wilde by Moses Kaufman which powerfully weaves together material from a range of historical sources to give us an insightful take on the events leading up to, and including Wilde’s incarceration.

Back home in Delhi I greatly enjoyed Gentlemen’s Club by the Patchworks Ensemble which looks at the stories of a set of drag kings switching between electrifying performances and fantastically written dialogue. Anirudh Nair and his company The Guild of the Goat, (who I subsequently collaborated with on Contempt during its most recent run in Delhi), gave us Sonnets c. 2017, a contemporary take on Shakespeare’s sonnets that plays fast and loose with questions of gender and sexuality, while also doing very interesting experiments with form.

This article appeared in Oberon Books on December 5, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Oberon Books .

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.