Since Argentinian physical theater troupe Fuerza Bruta burst onto the scene in Buenos Aires in 2005, some 5 million people in more than 30 countries have experienced its high-energy, postmodern productions, which are often tailored to wherever they’re staged.

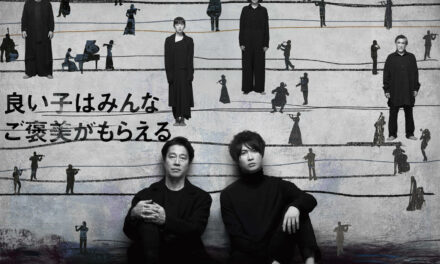

This time, the stage is Tokyo’s Stellar Ball theater, which is next to Shinagawa Station. And audiences there — who are better described as “spectators” — are being treated to the world-premiere run of Fuerza Bruta Wa! Wonder Japan Experience.

Although the show has been fashioned for today’s Japan, creative director Diqui James says its inspiration goes way back.

So, once inside the 800-capacity venue, people are led into one of several “tents” in which images of Japan are projected. There aren’t any reserved seats, and almost anything goes during the 70-minute spectacular to come — apart from flash photography.

The show then kicks off into an unstoppable barrage of lights, music, and action. As the tents are whisked up and away and everyone’s free to chat or dance or cheer as they like, drum rhythms fill the air and acts perform one after another, starting with platoons of performers in casual kimonos swinging from wires overhead. Meanwhile, a samurai in armor is sprinting to stay on a conveyor belt, smashing his way through walls as they move toward him one after another.

On the stage, you’ll see people walking up waterfalls and actors dressed as Japanese dolls who turn round and round on plinths before being propelled on rails so they’re hanging upside-down from above.

And that’s not all there is to marvel at before a massive clear-plastic sheet the size of the venue’s floor descends full of water and four women dive in and swim around. The pool comes so low to the ground at points, spectators may feel like they can almost reach out and touch the mermaid-like aquanauts above their heads.

In fact, many of these stunts have appeared in previous Fuerza Bruta productions — including the only other Tokyo show that ran for seven weeks in 2014, when the man on that conveyor was dressed as an office worker, not as a fearsome warrior.

What really sets apart this iteration is the way it’s modeled from start to finish to be a Japan-concept experience in terms of the sets, costumes, music and also the cast, of whom half were chosen locally by audition.

Instead of the previous time’s Latin American carnival music, for instance, “Wa!” rocks to originaL Japanese matsuri (festival) music played on traditional taikō drums, a zither-like koto, bells and a yokobue flute — all thanks to Gaby Kerpel, the company’s long-standing musical director.

Most crucially, the whole visual effect relies on Japanese aesthetics — from folk-craft graphics along the lines of the Tokyo Olympics logos to hanging cloths and curtains bearing beautiful designs of ancient family crests, calligraphy, drawings of fish and flowers, as well as kimono-style costumes adorned with ukiyo-e prints, albeit in super-bright colors. And then there are those two huge noh masks, one of a regular woman and the other a female demon, that everyone entering or leaving must pass by.

When I meet Diqui James, who co-founded the troupe along with his compatriot Fabio D’Aquila, there was no mistaking his delight on the day after the first full rehearsal.

“I was very satisfied with things yesterday,” he says, “so now we are changing lots of things to make it even better — some of the scenes, the lighting and the music.

“It’s very exciting and it’s the part of my job I like best because now the whole toy that I’ve imagined for such a long time has been built.”

Then, recounting how he arrived at his full-on approach to theater — about which he’s on record saying, “I don’t want audiences to commit any intellectual acts such as understanding the story” — the 52-year-old creator details how he quit an acting course at university in Buenos Aires when he was 19 because he realized what he wanted to do was different from conventional theater.

“Back then in 1984, there was a feeling of liberation as the country returned to democracy after the military coup in 1976. There were lots of new painters, dancers, musicians, and dramatists like me in that period we called ‘spring,’ and we all collaborated together,” he recalls.

“So when we started with nonverbal street theater, it was like an explosion of creativity — and I believe the spirit of what we are doing now is related to those joyful times when we were breaking out of the past.”

James formed a company called De La Guarda in the mid-1990s and was invited to take it to arts festivals all over Europe. In 2003, he even brought a show titled Villa Villa to Tokyo. Despite that success, though, he decided it was time for a rethink — so he wound up De La Guarda and formed Fuerza Bruta, whose name translates as “brute force.”

“We always wanted to make theater for everybody, not for elite circles,” he says. “For example, in my country, not many people could afford theater tickets. That’s why I wanted to make theater that anyone could enjoy and understand. Consequently, we’ve always tried to create works in a universal language.”

Finally, he explains, “the other big event” in his performance-arts life besides Argentina’s liberation from dictatorship was his “mind-blowing cultural experience in Japan.”

“Since my first visit with Villa Villa, I’ve loved this country so much even though I couldn’t read any signs and it took so long to make myself understood,” he says. “For me, it was such an emotional experience to see the audiences become instantly attached to the show. At that moment, I discovered we are basically all the same as human beings even though we have different cultural backgrounds. That was, and remains, a big thing for me.”

Long before then, however, the director-creator says he already had a special feeling for Japan.

“This has always been my dream country because, when I was 7, my grandparents came here and afterward they talked nonstop about how different and beautiful it was. Then when I was 18 I saw Akira Kurosawa’s 1985 film masterpiece, Ran. I loved it, and next I got into butoh dance a lot,” he says. “Then 12 years ago, when a Japanese producer from Amuse suggested I should make a special Fuerza Bruta production for people here, I leaped at the chance — and Wa! is the result.”

So it’s thanks to Kurosawa, and those globe-trotting grandparents, that we can enjoy this brand new nonverbal extravaganza fueled by its creator’s feelings and fantasies — and how timely it is along with other “universal” shows launched here recently catering to the growing number of overseas tourists, as well as fun-loving locals.

Finally, as our meeting signs off, I ask James if he has any advice for young Japanese artists dreaming of a career like his that has taken him from the streets of Buenos Aires to staging one of his shows more than 3,000 times in New York.

“Just do what you want to do,” he replies. “Do it with anything you have — and go for it!”

Fuerza Bruta Wa! — Wonder Japan Experience is at Stellar Ball Shinagawa through Dec. 10 (¥7,600 in advance, with VIP options costing extra). For more information, call 0570-550-799, or visit www.fbw.jp or www.kyodotokyo.com/fbw.

This article was initially posted on TheJapanTimes.com Reposted with permission. For original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Nobuko Tanaka.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.