These past two years have proven how much of a home the theatre is, something many only realized when its physical form was taken from us. The theatre provides community, empathy, a collective experience that makes the universal personal and powerful. This has been a true sentiment since the art of theatre began those many centuries ago: a space for the creation of artistry is also our accepting, educational home. Losing one’s home is painful.

We are not the first to lose our theatre, of course. The threat has loomed many times before. One such threat happened in 1978: as difficult as it is to believe now, Radio City Music Hall was set to be sold and transformed into a mall that year. Protests broke out, a defense for the home they so loved.

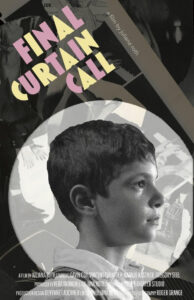

Screenwriter and playwright Juliana Roth’s great-uncle, Ray Bohr, was the organist for Radio City at the time. His story—one of dedication, craft, self-discovery, and friendship among hardship—struck her beginning in 2019. Now, three years later, her film about his life is in post-production, and they’ve nearly reached their financial goal. I was lucky enough to be able to chat with her about Ray’s story, balancing the theatrical and cinematic, and the necessity of telling this story now.

Rhiannon Ling: Firstly, for our international audience who may not know you yet, can you tell me a little about yourself and the kind of art you create?

Juliana Roth: I am a writer, filmmaker, and educator. I work across genres and disciplines: I really just love words and stories, so I’ll work in whatever form feels right for a given piece, but I primarily write literary fiction, screenplay (narrative and episodic), and sometimes poems, plays, and essays. Teaching is a big part of my creative practice and who I am as a creator. I find the classroom is a great space to encourage a diverse set of interests and, hopefully, help others figure out what their story is and what they want to devote more time to, whether that’s writing or something else altogether.

I like learning different forms of storytelling. There’s a set of constraints and freedoms depending on the form you use: with producing a film, you’ll often need a budget and team of people, but for a short story or a poem, that can more or less exist with you alone in a room, and maybe you end up publishing it in a journal or book somewhere, but the process of sharing it with an audience is just a bit different. So, I will try ideas out in different genres to figure out what suits them best.

Sometimes, I act, but I haven’t really done much of that lately. I was in a small play last summer with WCT Theatre, but now I just do things like table readings with friends to keep a toe in.

Ling: Final Curtain Call is based off the life of your great-uncle, organist Ray Bohr, whom you began actively researching in 2019. Can you tell me a little about Ray and his life?

Roth: Ray was the Chief Organist at Radio City Music Hall until 1978, the year the Music Hall was planned to be sold off to become a mini mall and a series of major protests organized by artists across the country broke out to save the theatre. Ray had succeeded Richard Leibert, who’d held the post since the opening of the music hall in 1932, but he also played around Manhattan at other iconic spaces like the Rainbow Room and the Paramount Theater.

Ray started his musical training at five, and, in his teenage years, would play professionally in local theatres and churches, along with working with M.A. Clark and Sons to repair and restore organs. He also served in World War II and played for President Franklin D. Roosevelt at the Iwo Jima memorial. When he came home from the war, he was an organ demonstrator for Wurlitzer until he became an associate organist at the Music Hall in 1947. He came from a large, complex family, and was a gay man during a period in New York where that was not as accepted as it is today, but he was part of a theatre community which was—relatively speaking—a safer space.

Ling: What initially drew you to Ray as a person? What began that process of research and creation?

Ling: What initially drew you to Ray as a person? What began that process of research and creation?

Roth: Looking back, what I think I was doing was creating a myth, or exploring the familiar mythology of “becoming an artist,” through his story. I think I was questioning my own value as an artist and if I could make a life for myself as a writer. I’d just finished my MFA and was unsure of where I wanted to go next. A woman I was housesitting for in 2019 offered me a volunteer gig with a local film nonprofit, which then turned into a freelance job, and then I got another freelance job writing grants for a small theatre company, and then I was eventually hired by a Broadway composer/pianist who I was assisting with his touring Broadway shows until the pandemic hit. I really knew very little about musical theatre and they had to print me a circle of fifths to keep on my desk so I could put together the music books in the proper key. This whole time, I was writing, and the jobs I was finding felt like little breadcrumbs. I’d been interviewing my family about Ray around this time, and it was just like…the pieces came together to allow me to write about a world I previously knew nothing about. I was suddenly immersed in a space with people who really lived and breathed the music of this time, and I was also getting to watch a lot of great movies. So, when we went into lockdown in March 2020, I just wrote as much as I could and started sending drafts to people who knew the world better than me and who I trusted as filmmakers.

Around that time, I brought what I had of the story to Pat Charles at The Writing Pad. He helped me push past the limitations I was putting on myself in wanting to stay so close to history. He, along with my peers in the class, helped me think bigger about the world I was creating. In those sessions together, I allowed myself to weave in other historical figures and situations that, as far as I can tell as a researcher, Ray was not apart of, but through these invented moments and scenarios, I could explore the questions I was most interested in as a storyteller: class, institutional power and labor rights, intergenerational stories and family systems, what happens to artists as their expression becomes capital, and…you know, the joy of complicated romances and friendships, plus all the visual fun you can have when writing and filming a live performance of music or dance.

I see Ray’s life and the world he inhabited as the seed for a larger world of invented characters and conflicts. For that reason, no matter what shape the story eventually takes, it will always be dedicated to him or inspired by him, but I would never want this to be seen as a documentary representation, [though] even documentaries question if you can tell the full story.

Ling: Have you found anything about your great-uncle that surprised you?

Roth: I didn’t know very much about him at all when I started this, so pretty much everything I found out I was surprised by. In particular, I hadn’t known how early he began as a musician or much about his personality. Of course each family member has their own memory of who he was, but in general it sounds like he had a great sense of humor balanced against a real dedication to craft.

I also had some pretty surprising moments during production: the family who now owns the home Ray bought for his family and spent a lot of time in himself throughout his life, they’d met Ray and knew his siblings, and the day we filmed, a neighbor who knew Ray came up to say hello, and more and more I found myself on the path of people who knew him in passing, and that felt a bit like, okay, I’m in the right place, doing the right thing. Maybe it was Ray saying hello.

Ling: You’re telling a story about your family, in a way. Has that offered any new pressures when creating?

Roth: Yes. There are tensions of not wanting to disrespect his memory or anyone’s memory of him while having the creative liberty to invent a fictional character. I don’t want to be seen as an expert on his life or give the impression that what I’m creating is a documentary portrait of someone. I hope that my family will understand this and feel proud of what I make, regardless of how much it reflects the “true Ray.” I also hope that this is something Ray would want and understand as an artist himself, especially someone who was so engaged in theatre and film, very performative spaces. This short film is also being used as a proof-of-concept for an hour-long pilot I wrote. If the pilot is picked up or the project turns into a series, I’ve played with the idea of changing his name to help create more of a distance.

I come to film and writing through the lens of fiction and narrative storytelling. I think of Mark Twain saying, “Never let the truth get in the way of a good story.” That really is how I approach my research process. Unless I’m in the nonfiction genre, I allow myself to invent an exciting plot informed by what I’ve studied, but not totally loyal to it.

I think a lot of memorists and nonfiction storytellers come up against ideas of truth and accuracy. I’ve told my family members what I’m doing and my approach, and allowed them to share with me how they feel and if there are any concerns. When I put out something slightly more personal, I do ask for them to read it over. I also do this as a way for me to just ask myself to look others in the face before sharing something so as not to forget where it comes from, and to see if I still want to after doing so. I think that could be mistaken for people-pleasing or not taking a creative risk, but I think it’s important to make sure you can stand by your decision in the long term. So far, everyone has been supportive, and luckily are fans of the arts, so understand what a creative process is and how what is created is never going to be the full thing.

Ling: Have you found any of yourself in Ray, whether as an artist or as a person?

Roth: I started writing around the same age that he started playing music, in early childhood. I think mostly what I found in Ray’s story was the freedom to own the desire to want to be a professional artist. I was often the youngest person, and usually one of a few women, in a lot of the “professional” artists spaces I found early on, like my MFA program, conferences, etcetera. I felt uncomfortable with taking up space and like I was somehow wrong or greedy for wanting a big life, for telling stories to be my life. In creating Ray’s character, I started to look at myself like…uh, why wouldn’t you want to pursue something you’re really good at and that you feel like you have to do? Who is it serving to shrink yourself?

Ling: Why did you decide to craft Ray’s story into a film, as opposed to another art form?

Roth: This world is just so cinematic. It was hard not to book multiple days in the theatre and church just to get more and more of that environment on film, but the cost of doing so definitely made us more strategic. I just see this story as images and feel the world is translated through what’s most available through film, largely that I can integrate movement, dance, and music. I also think if this went to series, the world has so many characters potent with their own possibilities, so I can imagine going off and following them for episodes and looking deeply at who makes up this community of performers: all the energy that goes into putting on a show at the music hall, plus everything that happened with the protests. In the pilot, there’s a dance sequence at City Hall that absolutely has to be on film! I can’t imagine it another way at this point.

Ling: Ray’s life is inherently theatrical, being surrounded, as he was, by theatre and cinema. How did you strike that balance between stage and screen?

Roth: In writing the short film version of the story, I narrowed in on just a few of the character’s traumas and how that pain still affected them as an adult. I used these moments as ways to move back and forth in time, so we’re able to be both in the 1920s and the 1970s. As I work with my sound editor, I intend to design the sound to create these motifs even more and to let us enter a bit more into the mind of a musician. There are a few moments of Ray playing throughout different ages in the film, and I incorporate a “final dance” by the end to show his progression as a character, how other performers are now involved, invested, and affected by his music. I didn’t show anything yet of him playing alongside movies, which is part of the history of organists at this time, too, but I do think we made the most of the camera to tell a visually interesting story that plays a lot with composition and light.

Ling: Why is this story important to tell now?

Roth: To me, the tragedy of losing a theatre is the erasure of a space. Not just the performers who were facing the loss of their home, but the managers, the clerks, the delivery people, the concession workers, the janitorial staff…what I mean is that there is more to these communities of artists than the flashy shows. I think artists now understand in a visceral way what it means to be cut off from their medium pretty directly because of how we needed to adjust as a community to take care of each other during the ongoing pandemic. I know so many inventive spaces were created as a result of this change, such as Zoom performances or other ways to continue virtual expression, but I know that the loss of a live audience, and the physicality of a space, all of that really was a huge shock and truly something to grieve. Some artists won’t come back even as it becomes more safe to do so over time.

If you’re someone who values the arts either as a creator or an audience member, I think this story will, or at least I hope this story will, capture the complexity of that loss as well as the resilience and endurance needed to protect your individual expression. I resist the common advice that practicing our art should always feel pleasurable and be easy: that I hope does happen and is important, but sometimes creating forces you up against difficulties, sometimes it’s a struggle, sometimes you get in your own way. I think that reality is just as important to show as the bliss and almost otherworldly experience of being in flow.

Ling: Finally, I’d love to give you an opportunity to plug yourself (as you know I love your work)! Where can we find you and your projects?

Roth: You can find me at www.julianaroth.com, where I have some links to my published work and other projects. I have a web series called The University you can watch here and follow for updates here. That series focuses more on the sense of institutional betrayal many survivors of sexual violence feel, as well as the myths around sexual violence present in many communities. I wrote that one pre-MeToo, so it’s been incredible to see how much the culture is shifting, but also how much we are still learning, too. The project was produced at the University of Michigan, where we are now only understanding the intricacies of a culture that supported over a thousand athletes being abused by Dr. Anderson among continued harassment and assault faced by students. I’m working with an activist to finish a discussion guide for the pilot cut of the series, which includes an unseen ending, and is exclusively available for educational screenings with Films Media Group.

I’m also available as a #PreWGA screenwriter for hire and have a portfolio of projects in development you can read about on my Coverfly profile here. Behind the scenes, I’m sending my books around to publishers and love to collaborate with others, so I’m always looking for a rich story to plug into however I can and to find the team who wants to get there together. Right now, I get to do a lot of that through teaching—guiding students to identify and refine their own stories—and I always hope to do a bit of that wherever I end up. It would be so fun to be in a Writers’ Room telling a collective story with other writers, so that’s always a little bit on my mind, too.

To watch the trailer and support Juliana and Final Curtain Call, please click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Rhiannon Ling.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.