During an artist talk just an hour before performing Wot? No Fish!! on Saturday at the Sydney Festival, English writer/actor Danny Braverman observed that as an artist he seeks “to foreground universals in a way that is not clunky.”

One might take from this that the artist’s craft lies in making a space for what is universally significant, through presenting, but not massaging, the details that constitute human life.

In Wot? No Fish!! Braverman is aided by the material with which he works: a selection of around 70 of 3,000-or-so miniature artworks by his shoemaker Uncle Ab Solomons, who drew a picture on the weekly wage packets he gave to his wife, Celie. Ab was obviously guided by the particular: each week’s piece depicts literally or figuratively something of the previous seven days of married life.

Each work is the product of a weekly sabbatical, a moment in which the shoemaker – I found the detail that all the little works had been stored for decades in shoeboxes quite fitting, to say the least – would sit down and concentrate solely on making something beautiful for his wife.

Wot? No Fish!! Sydney Festival

The way Braverman approaches such personal pieces is to draw his audience into the community of his family home. Enacting his earlier claim that theatre can build community, Braverman made the theatre into a kind of living room, offering the audience pieces of gefilte fish, together with their all-important chrein sauce.

Those in the audience who knew this homely delicacy swapped stories and voiced opinions about how they should be prepared. Boiled? Fried? How unthinkable is it for the chrein to contain mayonnaise?

Then, as the smell of fish wafted, Braverman told how he once woke up in hospital after a life-saving operation and knew he must still be alive because of the pungent odor of fish-balls. And the sound of his parents arguing about whether he should commence convalescence with his gefilte boiled or fried.

The performance’s title eventually linked both to what we had all eaten, and what Braverman had smelled, in the context of a picture wherein Uncle Ab and Aunt Celie visit their son Larry in the mental asylum. We already know at this point that Larry suffers from autism and epilepsy – not insanity. The asylum is the only institution that will care for him outside the family home, and the decision to place him there is bitter.

Gefilte fish thus gives a vital key, emphasizing Braverman’s seeming joke earlier that life for the Jewish people is, like chrein, “bittersweet” and “indelible”. Humans are, Braverman observes, caught between generations in something like a double helix, so that past and present constantly intertwine.

Wot? No Fish!! Sydney Festival

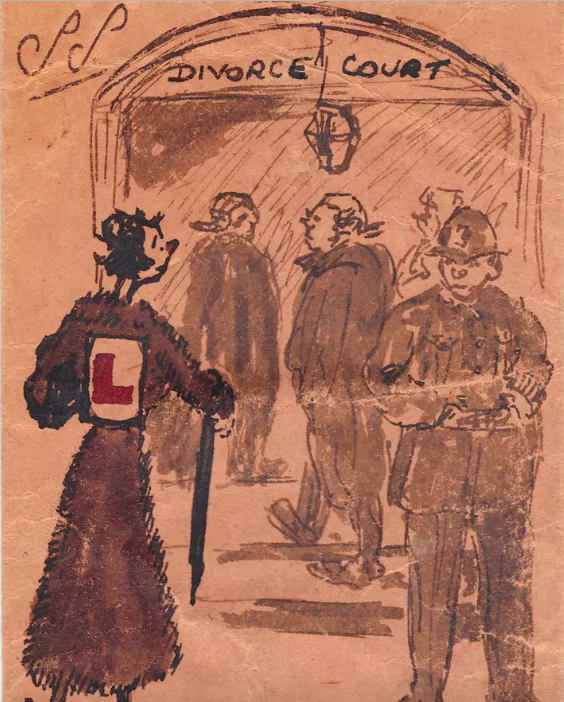

This point is visualized several times during the performance. For most of the time, Braverman sits at a table, where a projector enables us to see what he sees before him on a screen behind him: not only the artworks but also one significant document and an illuminating line-up of photographs toward the end.

In one instance, two pictures form a frame to the left and right of bittersweet artworks center stage. Attention is drawn to a picture of Larry with his parents visiting him in the asylum. “You can go home now,” he says.

Then another replaces this image: Ab and Celie face away from each other, sitting on a bed in the middle of which is a solid brick wall. On the right, we see Larry as a small boy standing on the beach with his aunt Lily (Braverman’s grandmother); on the left as an older man with his father in the rain. The pictures are made just five years apart from each other and we have already seen the brick wall.

The most consistent detail in the pictures is Celie’s red nose. Braverman learned from his mother that on her wedding day Celie awoke with a horrible cold, making her nose red and swollen. In her discomfort and embarrassment, Celie had to be “cajoled” to marry as planned. Braverman surmises that the red nose is always in the pictures because Celie is forever Ab’s bride.

Braverman observed when interviewed that the show is really a dialogue between himself and his dead uncle. Many are the moments when he seems to ask his now absent uncle the meaning of a detail. But the very gaps in his knowledge and in ours become the powerful space in which the significance of these little pieces of art emerges.

Braverman formed a community during his performance, and thus eased the challenge that he presented to us.

We were asked to recognize that the particularities of everyday existence have enduring and universal human significance. And so the universal became foregrounded by the particular. Every detail counts.

This post originally appeared on The Conversation on January 20, 2015, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Renée Köhler Ryan.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.