Heidi Latsky is a dancer and a choreographer who puts her vision of an inclusive integrated world on display, unapologetically. Her dance company Heidi Latsky Dance has been at the forefront of multidisciplinary inclusive performing arts for years, staging vulnerable, thought-provoking, transformative pieces. One of many projects spearheaded by the company is now a global community-building phenomenon ON DISPLAY GLOBAL – an annual global live installation celebrating representation and inclusion of disabled persons. In conversation with The Theatre Times, Heidi Latsky elaborates and reminisces on some of the most influential moments in her and her company’s history.

Irina Yakubovskaya: Why did you choose dance as the form to explore expanding what inclusion looks like in the world? What prompted you to create your company?

Heidi Latsky: I am in a precarious position. I am a non-disabled leader of a physically integrated company. It is a company of disabled and non-disabled artists. I have a lot of, probably more than most, disabled dancers in my company. and yet, I am the leader. I am the founder of this company, a choreographer, and so I have found it to be like the changing of the guard. It’s hard for me because it could impact my company. I have been evaluating and reevaluating and trying to figure out how do I continue as an artist and make my work accessible and do everything I really believe in in this new climate. One of the things that were naturally happening anyway with all my work was that it was becoming very intersectional and very inclusive. If you look at my D.I.S.P.L.A.Y.E.D. cast, which is the last large piece I created, and the piece I seek to get produced, – of the 17 performers in this project, half of them have disabilities. I also have people of color, people of different ages, gender identity, sexuality, there’s definitely a wide range. Do I cover everything? Absolutely not. For me, even though I am very connected to the disability community and I am an ally, I feel like my work has shifted more inclusive. I don’t pretend that I can include everyone but for me, my vision of the world has always been an inclusive one. When I started to incorporate people with disabilities into my work, especially in a dance medium, it’s so clear when you have bodies on stage that are not conventional. Everyone is different, that’s my vision of the world. I never understood the homogeneous thing. It totally made sense that I ended up in the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane company. The company I was in – I remember, I was so new to dance then, and I was from Montreal and there was this guy in the audience from Montreal and he took a picture and said “you guys look like a circus act” because we were so different. There was a very large guy, very tall, and I was very short, I had a lot of hair. There were so many different people on that stage, we all looked so different. And I loved that company. It was because of that particular company at that moment in my life I started to understand that dance could be sociopolitical. Dance could be so beautiful when you have different people with different life experiences but also ways of moving and the juxtaposition of that started to really intrigue me more and more, and that’s where I’m at right now.

IY: Was there a turning point that inspired you to actively start building an inclusive dance community?

HL: I was introduced to this gorgeous dancer Lisa Bufano. She got a grant to create a solo, but she wasn’t a trained dancer and she was a bilateral amputee. She came to NYC and she was one of the best performers I’d ever worked with. I was in heaven. It was because of her that I was able to see what I wanted my dancers to do which often times it’s trained out of them, which is to be very vulnerable and fierce in your conviction and in your commitment to the task. She was all that. Because of her, I started working more with people with disabilities. Because of her I met many disability activists in the NYC area, they joined the company and we created the piece called GIMP which was very controversial at that time. They were the ones who pushed me to really stay away from any kind of sentimentality. This is why we have a policy of no children participation in ON DISPLAY because children just by being there automatically invoke sentimentality.

IY: How did the project ON DISPLAY come about?

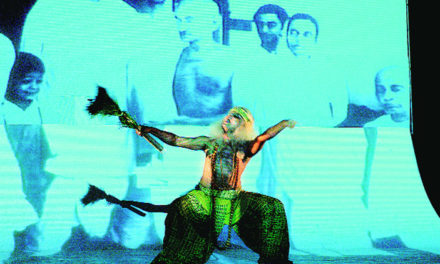

HL: The idea of the sculpture court which comes out of the piece that was commissioned by the mayor’s office for the 25th anniversary of the ADA, and the whole idea was for me to expose the general public to people with disabilities. I remember asking the commissioner if it was okay if I did it in an integrative context. He said, of course, that’s what you do. We created these sculptures in the middle of Times Square where they were really still, and then they would move, but they had agency. Their eyes were open. If I open my eyes and someone is looking at me and I get uncomfortable, I am allowed to close my eyes as a performer and slowly shift my gaze away from that person. Or I can stay looking. It is a very empowering and vulnerable [process] for the performer. We have been doing that since 2015, and it has grown into ON DISPLAY GLOBAL which takes place annually on International Day of Persons with Disabilities established by the UN. We started in 2015 in two sites: in NYC and Hobart Australia. Now we have over eighty sites all over the world. We all do it on December 3rd, and this year we are probably going to do it virtually. We are going to have a big global Zoom event. ON DISPLAY GLOBAL is a labor of love, we don’t charge anyone to do it, it is a collaborative community effort, and we want to keep it growing. One of the things I am trying to do is to explore who the ambassadors are. I would love to have more people with disabilities spearheading these installations. We work with each person on how to produce an event. This project is an antidote to COVID. It is a global movement that brings communities together. Even if we do it on Zoom, we can see everyone being sculptures in their own homes, and the audience is in the mix just like they would be in an installation. It is something that I am committed to. It would be great if it could become an independent project.

IY: The concept of being “on display” is often perceived as controversial, as it involves the issues of gaze, objectification, and performativity. How do these projects address the exposure of disability experience and its integration in the global human community?

HL: The first half of D.I.S.P.L.A.Y.E.D.contains descriptions of people in medical [and demographic] categories, for example, male, 29, dark hair. The first half is this robotic voice just stating these characteristics. [As part of the research for the project] a board member went out and watched people on the subway, real people. What you see is this beautiful sculpture court with 17 sculptures who are people, performers, and they are kind of frozen. Then they start the movement and the moment of change when all the dancers start moving more together. The first section of D.I.S.P.L.A.Y.E.D. is this robotic score, and the company breaks out and then reforms. We really get a sense of people in motion, moving through space.

In ON DISPLAY, the performers are live sculptures for the purpose of being seen and witnessed. They are being witnessed in their incredible vulnerability which to me makes them fierce and to me, you put a dancer or anybody and you say ‘you can’t move, you can’t’ speak’ – everybody is going to feel incredibly vulnerable and exposed. Some people in the disability community have said to me that it’s not a good representation of disabled people because they are not dancing. I say it’s an act of endurance and an act of complete focus. It is a great performance exercise for any actor or dancer because you have to be authentic, you have to stick to the task, so it is challenging. It is also beautiful. I am a slash and burn dancer; I love technique. I love watching my dancers move with athleticism, whatever their athleticism is. I was very surprised at how much I love ON DISPLAY, and I realize that I love it only when the performers are so in it that you really see them. That to me is exquisite, interesting, and fascinating. I’ve seen over a hundred installations. Allowing the general public to actually experience disability and difference, while usually, it is not even in their life.

IY: I appreciate you saying that when people are fully immersed in experiencing the performance, they (audience) truly see the performers in an empowered way, as opposed to impersonal art pieces on display. At the end of the day, just with any other public art be that a photograph, a painting, or a performance – you put it out there as an artist and you can’t control what people are going to feel and think. At the end of the day, it is hard for artists to let go and let it live and resonate with others but it’s a risk that must be taken.

HL: It is important that disability is seen in relationship with other communities, not as just one group. It is the disability community interacting with all communities. The power of ON DISPLAY is that it is live, so people are witnessing a real person. I have tried to run my company according to my beliefs in tolerance and acceptance, treating everyone the same.

IY: What moments of your career would you call the most inspiring?

HL: I have had revelatory moments. I have had experiences that have taken me to such a beautiful place. For example, working with Lisa Bufano was one of those major shifts for me. Working with Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane was another major shift for me. I started dancing when I was twenty, and I had a very narrow idea of what dancing was. When I worked with them, I saw how impactful dance could be and how it could be art as opposed to beautiful athletic [practice]. I had moments of watching my dancers, at times or watching my sculpture courts and being completely awestruck by the beauty of the person, not the actual installation. True beauty is in the surrender and it is also in the complete commitment to a task. When I teach students, when I look at ON DISPLAY, when I look at my choreography I always am training and pushing for this commitment to the task. I see how beautiful people are when they do that. It is a major drive for me as an artist. I’ve developed a whole meditative practice to teach people how to do that. It is called MARS – Mindful Activation Release Study. It was developed specifically to teach people in my company, in particular performers with disabilities, because I felt like they had no access to training, and I didn’t think they would necessarily benefit from traditional dance classes. I started thinking about what my company could do together, so I developed this training. I am now focusing on training other teachers on how to teach MARS.

IY: Issues of diversity are more present in the public American mainstream discourse now than they were several years or even months ago. Do you feel like disability is fairly represented in today’s discourse?

HL: While I have seen a shift [over the years], we still have a long way to go. When I first introduced performers with disabilities into my work in 2006, I was trying to get people to come to see my work, and there was no interest. It was categorized as ‘community work’, and I kept saying no [to such categorization]. To categorize it as ‘community work’ meant that they saw my dancers as amateurs. I had to fight this. The work was being downplayed as ‘community work’ because some of my dancers were disabled. There has been a shift [since then], and there are many people who are pushing for this shift to continue, for more leadership. I do think the disability community is still underrepresented.

IY: How did your projects shift in the increasingly more digital and multimedia-oriented world?

HL: Recently my trajectory has shifted toward filmmaking. Films Soliloquy and SOLO FLIGHT really speak to what I am doing now. I am also really interested in Artificial Reality, interactive experiences. I see it as another way of creating more accessible work. That is the focus of our company today.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Irina Yakubovskaya.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.