Shooting to stardom with their 2007 Edinburgh Fringe debut Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea, the British company 1927 have traveled via the international theatre and European opera circuit to finally reach the main theatre program of the Edinburgh International Festival 2019.

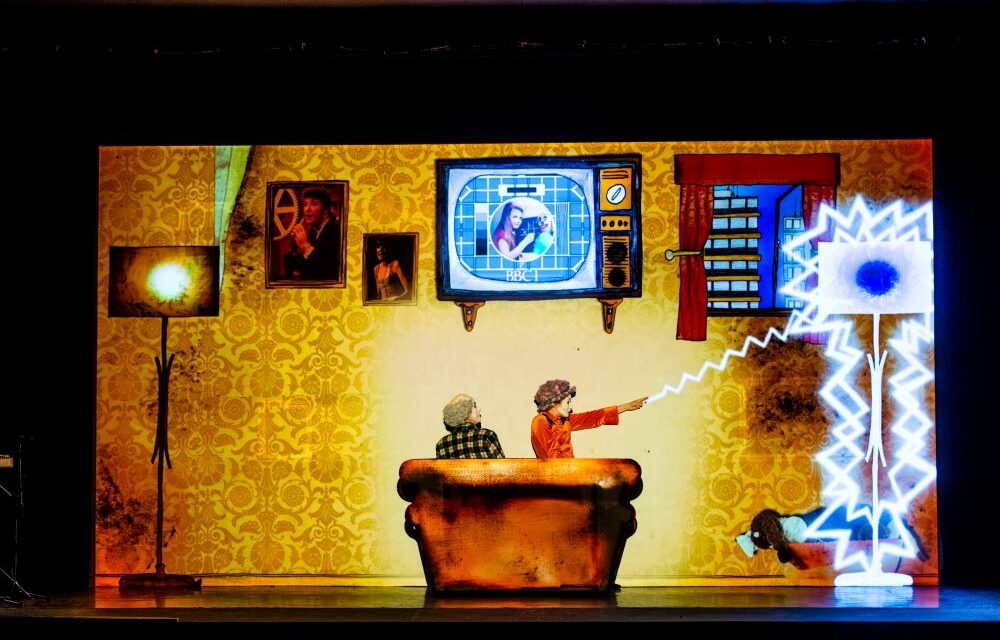

They chanced upon their unique style – a cross between silent cinema, cabaret, storytelling, and animated film – through a melding together of the respective talents and interests of animator/designer Paul Barritt, writer/ director Suzanne Andrade, performer Esme Appleton, and composer Lilian Henley.

There is something both remotely familiar and refreshing in this theatrical mixture that is best experienced directly. Their new show, Roots, premiering in Edinburgh, comes from the British Library’s collection of international folk tales known as the Aarne Index. However, inspired by Angela Carter and Italo Calvino-style interventions, writer/director Suzanne Andrade recorded the tales in her own words, sometimes riffing off the title or the stories’ short summaries. Rather than filtering the choices of stories through any pre-conceived thematic criteria, it was the impulse decisions and narrative taste buds of the other company members that determined which of the tales would get into the show and which would be left out. As a result, the only discernible thread holding these ‘folk jokes, anecdotes and stories from a simpler time’ together is their apparent absurdity (as well as possibly a community spirit engendered by the show). This is not an obviously political work by any means, but there is one passing invocation of the President of America in it and the director’s note itself does reference Brexit as an underlying motif in the show’s conception. Incidentally, and probably unintended by the company, the bleak black humor of their show is at times quietly reminiscent of the stories of Daniil Kharms, a Soviet avant-garde author whose work also managed to seemingly apolitically distill the absurdity of an unbearable political situation.

Hence, we get stories of greedy and bloodthirsty parents and children and a fat cat eating everything in sight starting from porridge and her mistress via school children, the devil, the god, the CEOs of multinational corporations and the universe itself. The most famous story – and the centerpiece of the show’s lucky dozen – is The Patient Griselda, a tale of female humiliation and limitless endurance immortalized by Chaucer, but featured here as ‘written, directed, based on the original idea of, and starring the King’. Often it is this sort of subtlety of the tone in which the story is rendered that helps to convey the intended take on it and forms the consistency of 1927’s style. Interestingly, it is the company members’ friends and family whose voices are recorded reading the stories and woven into the show’s soundscape. Its other highly significant element is Lilian Henley’s musical score, performed live here on a variety of hand-held instruments, which on this occasion replace the company’s trademark piano accompaniment.

The second half of the show is slower and, as most stories go, somewhat soporific in its effect. But the company are most probably aware of this. Half-way through their penultimate story, The Magic Bird, the amateur narrators they have co-opted for the show also get to voice their opinion of the company’s work – ‘I thought it was a bit long’ they quip about a previous show but exactly in sync with the general feeling in the auditorium at that point. And we all laugh in welcome relief at the absurdity of that moment too.

At the end of the day, the show as a whole is carefully thought through in its many facets, including the significance of the title itself, drawn from the concluding tale about the impossibility of escape from our own heritage.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Duška Radosavljević.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.