BAD co.- is one of the most interesting theatre groups from Croatia. The ensemble, lead by stage director, playwright and choreographer Goran Sergey Pristaš, was formed in the year 2000. The group’s productions, created through improvisation, span theatre, modern dance, and performance art. The core of the group are: Ivana Ivković, Ana Kreitmeyer, Tomislav Medak, Goran Sergej Pristaš, Nikolina Pristaš and Zrinka Užbinec.

As a combination of three choreographers / dancers, two dramaturgs and one philosopher, plus the company production manager, since its beginning (2000), BADco. systematically focuses on the research of protocols of performing, presenting and observing by structuring its projects around diverse formal and perceptual relations and contexts.

In the middle of a rather crowded space, on a stage cut off from the auditorium by the iron curtain. Squeezed in between others at a table, no way to see everything, always having to turn your neck to look at the other full tables, at the door on the opposite side where some kind of film noir action seems to be taking place, or at the small strip in front of a wall, which serves as a wide screen stage for dancing and cursing and projecting. Voices from radios, and voices from performers at the tables, almost whispering as if not to disturb anyone, barely audible across the tables, accompanied by some photocopies, but there is no time to really read or even understand them. Memories are made of this… performance notes, the title of this work by BADco. from 2006, quotes a Dean Martin song, but for the moment it is uncertain if it is not the other way around: We are in the middle of a memory machine – but does it produce memories or is it fuelled by them? What then does it produce? More memories? As with the famous Wunderblock – a waxed blackboard for children to write on, used by Freud as a metaphor for human memory – you can no longer really decipher what is beneath the permanently re-written first layer. But you also cannot ignore it.

Too much

There are at least two kinds of too much. One that annoys by exaggeration, that frustrates because you are never able to cope, that feeds you until you cannot swallow anymore. Too much of ‘anything goes’, too much gluttony and mindless consumption. And there is too much as a thoughtful offer of possibilities. Not just accumulation but too much that offers choices, that empowers, that frees even when it is overwhelming. Too much that opens a field of thinking, associating, experiencing. Too much that takes its opposite seriously. Too much as a gesture of invitation and generosity.

Tasks for guests and hosts

It is this gesture of sometimes overburdening generosity that characterizes many of BADco.’s performances. And even though this attitude can be read as the continuation of a specific modernist theatre tradition aiming to lay out a wide semiotic field by producing an excess of signifiers, this is not the full truth. While the work of their predecessors (most famously the New York neo-avant-garde antagonists the Wooster group and Richard Foreman, or in Europe – even though very different in style – the young Jan Fabre, Heiner Müller or Romeo Castellucci, to name a few) has its roots very much in an urge to liberate theatre from the primacy of text, from limitations by causal, linear narrations, by psychology etc., BADco. takes it for granted that this prominent fight from the 1980s and early 1990s was won long ago. Not only do they use the booty of these struggles in whatever way they need to – they also add to it the attainments of the parallel, often ignored story of the arts and theatre in (South-) East Europe, and especially the former Yugoslavia.

While the often dogmatic, didactical style of new theatre forms of the late twentieth century mostly put the audience in front of the picture as though listening to a sermon, BADco. invites its guests to be so close that they can almost touch them, or even lures them right into the middle of the image. The audience is always an accomplice and part of the game when each performance creates its own strikingly specific and always different situation – to the point of adopting space, dramaturgy, style, so much to the respective tasks, that the individual pieces often seem incomparable with each other. (The dance theorist Bojana Cvejić pointed out that this difficulty of pinpointing one recognizable aesthetic adds to the difficulties of selling the work to the Western theatre and art market). The focus on the ‘how’ of a performance wins over the ‘what.’

Each performance generates its own needs. This way the setting as structure and frame has become one of the core interests of BADco., sometimes even being the main character or topic of a work. By creating space (not only architecturally, but also dramaturgically, and most important: socially) rather than a narration, the collective claims the very centre of what defines theatre more than any other art form (despite all the supposed, so-called relational arts of recent years): Sharing space and (life-)time as a common experience and moment of true co-creation. Even if the audience, as in the choreography FleshDance (2004), is put in a frontal position, it is not kept outside since it is stretched alongside an extremely narrow stage, almost touching the performers, and having to constantly move their heads to follow the dancers, trying to get the full picture – which is always impossible since everybody is left with his own specific perspective. 1 poor and one 0 (2008) is a game with cinematic views, constantly shifting the angles, stepping inside and outside the image while the audience is placed on opposite sides, watching not only the show but also closely watching each other, whereas in League of Time (2009), the spectators mark the outside of a large playing field, feeling much more like watching a game in a gym than a drama in a classical black box.

That everybody receives and co-creates his own story is a truism not only in theatre theory since for some years (Meyerhold has already elevated the spectator to the role of ‘fourth creator’) – and still today, most contemporary theatre nonetheless wants to control the experience of their audience to the point of obsession, or to offer fake choices as is often done in so-called participatory theatre. The extent to which BADco. believes in the exact opposite becomes most obvious with Deleted Messages (2004), where the border between public and performers, between real and fictional space (another of BADco.’s leitmotifs), the choreographed and the spontaneous, are blurred to a degree where the show fundamentally risks itself and becomes just as dependent on the behaviour of the audience as on the artists themselves. Performed in a vast, crowded space with only one person per three square meters, constantly moving between an also moving audience, Deleted Messages is generous up to the point of self-abandonment. Where so much responsibility is handed over, choreography can only survive in constant negotiation with rules that are difficult to understand and to follow: It is a risky invitation into an unknown situation. No easier task for the guests as for the hosts.

Theatre was always closely related to the self- and the representation of society, it always mirrored, not only in its content but also in its form, the political structure to which it belonged. The Greek polis gathered in the Dionysus Theatre to negotiate their self-understanding as a community, in the Baroque, the monarch was the focus of stage and audience, and not by chance the awakening of the European middle-class was accompanied by the rise of bourgeois theatre as an aesthetical, but also very concrete, institutional, cultural and political phenomenon. In this context, it is not surprising that BADco.’s work – with, for example, its recent interest in the idea of German Volkstheater of the eighteenth century as a concept for popular, working class theatre – is not only the result of revisiting and self-positioning within an international theatre and art discourses. But that its understanding of space and the relation to the audience also have their very concrete roots in the situation of Croatia in the early twenty-first century, politically as well as aesthetically.

Metaphors for building theatre and society

Following the death of the Croatian president Franjo Tudjman in 1999, many hopeful initiatives started in grass roots politics as well as in the arts. A net of NGOs spread over the capital of Zagreb, but also extended to other former Yugoslavian states: Artists and activists revitalised old connections and new alliances where official relationships were often poisoned to the level of hatred. Suddenly it seemed possible to put an end to the repressive, traumatic atmosphere of the war, and the semi-democracy that followed under Tudjman, with its strong, one-dimensional nationalistic attitude. A young generation of activists, artists and theorists started with enthusiasm and hope to create platforms and networks for production and presentation; for discourse, discussion, and international exchange. Everything was fluid, and the borders between theory and practice, art and activism were not strictly drawn. It was in this atmosphere, as well as the spirit of protest and opposition to the rigid conservative structures and hierarchies of the established theatre and art institutions, that BADco. was founded in 2000 as a collective of quite different characters and specializations.

What started as a single project collaboration between theatre dramaturge Goran Sergej Pristaš, playwright and dramaturge Ivana Sajko (who later left the group), and the choreographers and dancers Pravdan Devlahović and Nikolina Pristaš soon developed into a long-term work and research project. Philosopher and net activist Tomislav Medak then joined the collective, followed by the dancers and choreographers Ana Kreitmeyer and Zrinka Užbinec, the dramaturge Ivana Ivković, and more recently the production manager Lovro Rumiha. Since each project creates its own needs, it also requires specific invitations: Over the years BADco. has included the aesthetics and opinions of such different personalities as the light artist Goran Petercol (2, FleshDance, etc. ), the composer Helge Hinteregger (Man.Chair, FleshDance, etc.), the multi-media artist Slaven Tolj (Changes), the software programmer Daniel Fischer (Deleted Messages etc.), and the architect Tor Lindstrand (Memories are made of this…performance notes) and many others.

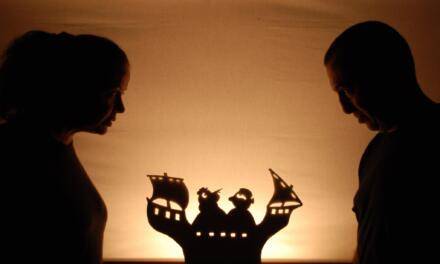

Memories Are Made Of This… (2016) performance notes is a project which, metaphorically speaking, travels within a complex topology of memory. It borrows the name of a popular Dean Martin song whilst exercising F. Scott Fitzgerald’s observation that “the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.” BADco. is approaching the topic of memory via a process intrinsic to it – forgetting – suggesting two possibilities of entering this complex subject matter: to think in terms of vacuity, blankness, deletion, and further on, mental fissures and emotional crack-ups. (Photo credit: http://www.badco.hr/en/work/1/all#!memories)

The performances may well be the most visible markers in the artistic as well as the theoretical development of the group – but importantly their body of work also includes a set of software tools for the analysis and development of dance and movement (Whatever Dance Toolbox, 2008-11), several video works, installations, DVDs, texts by and about BADco., lecture performances, as well as curated events, and laboratories. In the same way that it is impossible to decide whether BADco. is a dance or theatre company, it is similarly difficult to separate their theoretical research from their practical work. Besides the projects and works that are clearly labelled BADco., and their close personal connection with the performing arts magazine Frakcija and the Centre for Drama Art – CDU (both founded by Goran Sergej Pristaš), the group also has a major influence on the Zagreb arts scene via its members as teachers, collaborators in other projects, activists and political lobbyists for culture.

The media- and self-reflective attitude of BADco.’s work, with its intensive research into “the protocols of performing, presenting and observing” is also constantly triggered by the social and artistic environment of Zagreb, where structures and relations continue to be undefined and need to be regularly re-negotiated. An environment where nothing is certain, where economics, politics, and aesthetics are ever-changing and the financial situation is precarious not only for artists. More than ten years after the wave of optimism that followed Tudjman’s death, Croatia is still not a member of the European Union and much of the initial spirit of hope has been lost. The independent scenes in Zagreb are characterized by a sense of exhaustion. Many initiatives have ceased to exist or are permanently under threat of closure. The fact that the Soros foundation, which played an influential role in Croatia between 1995 and 2006, has now returned to the country in the form of a ‘crisis fund’ is seen by many, cynically, as a sign that things really are on the edge. While many artists have left or are leaving the country to seek opportunities elsewhere, BADco. has – also through having a network of co-producers outside of the country – become a reliable and constant factor of the artistic scene, regionally as well as in Croatia. Its ability to maintain a group with eight core members distinguishes BADco. at a time when economic factors have produced a flood of solos and duos from most other companies in this scene – not only in South-East Europe.

The performance Spores (2016) departs from the problem of never-ending work of maintenance. We maintain the body, the house, the family and the plants, we maintain friendships, relationships, cleanliness and clothing, we maintain infrastructure, organization, space and technology. (Photo credit http://www.badco.hr/en/work/1/all#!spore)

Back projection of the imagination

From the very beginning, BADco.’s art was based on the belief that artistic work cannot be separated from the means by which it is achieved. Collaboration, and investigating different working methods, are an integral part of the artistic enterprise: How can theatre pretend to fight for a more just society, and at the same time base itself on strong hierarchies and dependencies? How can the production and exchange of artistic knowledge be communicated in ways that are no longer considered the correct means of address even in classrooms? Such works as Deleted Messages are reflections on theatre as much as on society. Whereas in the experimental theatre of the 1980s and 1990s, the notion of audience shifted from spectator to witness (as Tim Etchells, director of the influential British company Forced Entertainment, put it – following Chris Burden – following Brecht), Deleted Messages pushes the relationship even further, handing over much more active responsibility and inviting the audience to take the role of collaborator. Society does not function by watching. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s quote, used in Memories are made of this…performance notes, brings to the fore what is crucial for BADco.’s theatre, but which can just as well be read as a metaphor for the difficulties of a society just learning how to use democracy: “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.“

Already the name is a statement: BADco., being the acronym for Bezimeno Autorsko Društvo (Nameless Association of Authors), believes that the group is more important than the individual artist, and at the same time strongly in the unique authorship of each member. This somewhat paradoxical idea of balance between collective and individualism might also be triggered by particular historic experiences, certainly it deviates from most concepts of contemporary Western collectives, with either their more romantic or more pragmatic approach. BADco. shares its name with a rock band that has existed since the 1970s – and despite the fact that there is no aesthetic connection, there is an affinity with the structural and hierarchical model proposed by the idea of bands in general: shared responsibilities, team spirit, common artistic goals, and the possibility of (at least in early punk) all being on stage despite different abilities and skills: From the outset of BADco.’s work, dramaturges and theorists were included as performers as much as the professional dancers. (The philosopher Tomislav Medak performed as early as 2002 in Diderot’s Nephew). Obvious deficits in body and training are not seen as deficiencies but as strengths, different abilities are not assimilated, they remain visible, and focus attention on something other than virtuosity and technique. Performer presence goes beyond educational professionalism. BADco. proclaims, in its own words, a “collective authorship, where boundaries between the respective competencies of performers, directors, dramaturges become blurred and where performances reflect how the group transforms, in multiple and diverse approaches, the initial artistic concern.“

It is perhaps one of the most beautiful dance duos of recent years when in 1 poor and one 0 the short-statured Tomislav Medak, together with the tall, full bodied dramaturge Ivana Ivković, dance an imaginary contact improvisation à la Steve Paxton that in reality neither of them is able to perform this way: Merely by describing precisely move after move. “I stand up, I stand tall, I offer you two points of support. One on my hand, and one on my thigh” – “I pose for a moment, I can’t decide, uh, well, let’s take the arm…” without ever touching each other. Images produced by our brain, projected back onto our retina. This back projection of the imagination is one of BADco.’s core techniques.

It is a duo that could not have been performed the same way by professional dancers; the inability to actually do the movements that are described produces the very gap that allows different and parallel interpretations to be evoked: It is a touching love story, a story of a carefully balanced relationship, as well as of relationships between human beings in general. And it is a story about the essence of the theatrical contract that has existed in different ways since the beginning of theatre: About the gap between representation, presentation, and reality. And even more: This duo does not only delegate the movement completely to the imagination of the spectator (and by this, again, create a new space and a new interdependence between stage and auditorium); the very concrete descriptions of movements produce a neuronal mirror sensation in the one listening. It makes the audience dance along more than any real dance ever could.

Theatre as invitation

BADco. walks a thin line between clearly acknowledging its heritage (coming from a country in transition that has been socialist for more than forty years, from a region with a rich art history, the importance of which is still not fully recognised in other countries) on the one hand, and a strong connection to particular aesthetical and philosophical discourses originating in Western Europe on the other. Perhaps Yugoslavia’s location as a state between the geopolitical blocs has prepared it a little for this in-between role – but it has its costs. Whereas in most Western countries, BADco.’s work is still labeled ‘Eastern’ (as if it needed protection through classification), in Croatia itself it is viewed with suspicion by many cultural institutions, programmers, and curators.

BADco. has found its own way across the clearly defined borders of conceptual dance, post-dramatic theatre, etc. A way that means it is not always easy to be accepted in the world of festivals and contemporary performing arts venues, where the former West is still the main playing field, the main market. So again and again the group’s experience is that – while in the performing arts scene their work is largely haunted by the image of being too complicated, too hermetic – a rather normal, mainstream-oriented audience, for example at the National Theatre in Georgia, appreciates and reads their work in a very emotional and direct way. So BADco.’s work remains estranged from the theatre market on both sides, while at the same time they draw on Western media culture as well as East European art history: Their first work Man.Chair (2000) re-staged (together with the original author) a piece from 1982 by the performance artist and member of the – at that time – influential neo-avant-garde company Kugla Glumište, Damir Bartol Indoš. League of Time is strongly influenced by Russian Constructivism and in the 20011 Venice Biennale they shared the pavilion with the late Tomislav Gotovac.

Man.Chair (2000) was developed as a work in progress piece presented in a form of public rehearsal with no premiere. The research was based on the repetitive capacity of authentic performance Man-Chair, first time performed in 1982 by Damir Bartol Indoš. (Photo credit http://www.badco.hr/en/work/1/all#!man-chair)

This sense of not really belonging – that BADco. shares with colleagues from other former Yugoslavian states – can be both limiting and liberating. In 2010 series of sessions held in Zagreb on the occasion of BADco.’s tenth anniversary, Bojana Cvejić highlighted a desire shared by many artists in the area: To act as host to others, to invite people into their own situations, to bring guests from abroad or nearby – a desire resulting from a precarious situation that implies always being dependent on others, always being treated as guests. Pursuing this idea, hosting implies a different relationship, a clearly defined space of one’s own, a territory that is unique and different, attractive for others to visit. It frees them from the West’s paternalistic attitudes and historic threats from the East. It defines a field of thinking and acting beyond the given aesthetic and political paths. Whether all the banks are owned by Austrian and Italian companies, all the houses at the sea bought by the English and Americans: There is a territory of art that is not dependent on the European Union, that defines its own borders – a territory to which guests are invited on their own terms. It is for good reason that hospitality is one of the constituting elements of civilization.

This concept of hosting defines both the work and working relationships of BADco. From the outset, it has been used as a strategy for involving people from different contexts, disciplines, and countries in the work. By creating a very specific dramaturgy of generosity within unique performative environments of sharing, that, as well as artistic implications also produce a resistance towards a culture of accounting, consumer-capitalism, neo-liberal evaluation-ideologies or imperialistic development aid, BADco.’s aesthetic generosity avoids a superior attitude towards its guests, because it is equally demanding of both hosts and guests. It is a generosity that does not coddle but rather asks for contributions and active participation. It means: Work. Working together. As an audience, we have to accept the invitation with all its implications. As masters of ceremony BADco. might not be the most casual hosts – but they are definitely concerned with taking their guests more seriously than most other contemporary theatre companies. So either we are willing to grasp whatever we can – or we walk home empty-handed.

This text was originally published in a catalogue accompanying BadCo.’s presence in the Croatian Pavilion at Venice Biennale. Reposted with permission of the author.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Florian Malzacher.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.