In the midst of the vibrant Dallas theatre scene, there lies a company of prize-winning political prowess, one whose make-up may surprise you: Cry Havoc, a theatre company founded in 2014 to create a space for teenage artists to create and explore new work. Yes, you read that correctly. This company of actors is composed entirely of teenagers, devising provocative new works of political resonance: in the past few years, they’ve tackled immigration (2019’s Crossing the Line), the #MeToo movement (2019’s Sex Ed), gun control (2018’s Babel), and many more. They’ve earned a name for themselves—both the young company and the guiding artistic team alike—by producing astounding shows of political resonance.

However, it didn’t start out that way. “It was originally about performing things that were a little bit edgier than Annie or Shrek: the Musical,” founder and artistic director Mara Richards Bim tells me. “It was really about wreaking havoc on the youth theatre landscape here in Dallas and beyond.” It was a place for young artists to cry havoc and let slip the dogs of war (or art, as it were). Its Julius Caesar namesake proved to be more applicable and appropriate than ever in the summer of 2016.

“We sort of stumbled into it,” Bim says, recalling the first decidedly political show crafted by her crew. That summer, police brutality had entered into the media anew, and Dallas had experienced its own tragedy in the killing of several policemen. “This was a long summer…there were obviously things and emotions that came up, and so we decided to create a show that dealt with that in our city.”

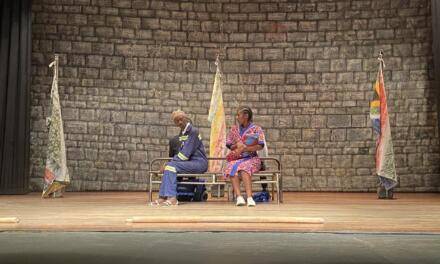

Cry Havoc’s team and its teenagers looked at how shows surrounding traumatic events had been devised in the past, drawing inspiration from shows like Tectonic Theatre Company’s The Laramie Project. Ultimately, they “decided to bring people in and do interviews, and stage those interviews,” Bim says. “We did that, and had no idea how resonant that would be.” Cry Havoc’s small space could seat 65; by the end of the show’s run (entitled Shots Fired), nearly 120 showed up each night, buying tickets to stand in the aisles and watch. Cry Havoc had found a niche, producing at least one new work of political resonance each year.

“It was very much just being here and looking for a way to process it,” Bim continues, speaking of the domino effect of Shots Fired: those interviews spoke not only of race but of guns, leading to Babel; when speaking to migrant families for Crossing the Line, the artists ran into issues of climate change, leading to a show on ecological disaster and climate justice. “Conversations we’re having lead to other conversations,” continues Bim, adding, “So not everything we do is political, but the ones that are—and there’s usually one a year that is—they just evolve from conversations.”

Cry Havoc Theater Company’s “Shots Fired,” 2017. PC: Kendalyn Aldridge.

The way these shows are crafted is just as impressive. Though the artistic team organizes, guides, and facilitates, the teenage artists are entrusted with an awesome amount. For verbatim shows (in which interviews are staged directly from transcripts), it is the teens themselves conducting interviews. “We try to get people from across the political spectrum to interview,” Bim explains, “so, for example, Crossing the Line, which was about child separations at the border: in the months before the students started, I and the co-director met with folks like the ACLU of Texas, who could connect us with people who could help us line up interviews. Then the kids are trained in how to conduct interviews…the interviews happen, we get them all transcribed, and then it’s piecing together a puzzle.” While Bim and the remainder of the artistic team are highly involved with the concocting and cohesion of scripts and story, the teens are involved every step of the way.

Cry Havoc does not simply do verbatim shows, of course. Their most recent—Committed: Mad Women of the Asylum, addressing the institutionalization of women in the late 19th century—was an immersive play, crafted from source material and improvisation. “It’s called process drama,” Bim tells me. “It’s improvisation, but the facilitator really facilitates the direction that it goes in. It’s a thing that’s done with young children often…but we did it over spring break with the teenagers. In the process, you develop this whole world, and characters, and storylines. So we did that, and we audio-recorded all the improvisations; there were some writing components to it, too: they would write letters or journal entries, things like that. Then I went away, took all of that, and pieced together a story. Then we come together and perform it.” Even in this performative realm, the teens are heavily involved in the creation from start to finish, their ideas, devisings, and findings contributing to the cohesion.

It is a remarkable thing to witness, in a world that so often tells young people not to speak on such matters. When asked why it is so imperative to respect, honor, and amplify the voices of young people, Bim responds, “I think they are very quickly going to be out in the real world, so it’s not only about amplifying their voices, it’s also about engaging them in conversations about real topics before they’re out in the real world as adults. [Through the creation of the shows,] they become really knowledgeable about a particular topic in a way that most adults are not. They go out into the world and they can share informed opinions, whatever those opinions are. And, because they are going to be voting and leaders soon, I think it’s important that we hear what they have to say. Adults have not done a very good job of creating a safe, healthy world, and sometimes we can take notes from those younger than us.” Clearly, Cry Havoc has done just that, holding a space for young artists to grow both under artistic guidance and in knowledge and empathy.

It is worth pointing out, as well, that Cry Havoc does not entrust young minds with these tasks and their inevitable growth lightly. Encouraging that aforementioned safe, healthy world, the artistic team takes precautions to care for their young company. “We learned along the way about what it means to listen to stories of trauma,” says Bim. For instance, when they “went to the border, we worked with a therapist before we went, and then after we returned, to help process those emotions.” The teens of Cry Havoc are not only trained in interviews and devising: they’re also provided with coping mechanisms, care, and emotional processing.

In addition, the company is paid. “It’s a way for us to show that we value them as artists and it also professionalizes the experience for them,” Bim explains. In a society that so often devalues the arts and the artists within them, it is a powerful step in the right direction.

This work has earned Cry Havoc a name for itself. They’ve received multiple grants and awards from Dallas-area supporters; they’ve been covered by their local NPR radio station; they’ve been in to meet several Senators during the creation of their shows. Their desire and ability to tell the story from all sides, their commitment to untold, evocative tales, their deft devising skill, and the sheer wonderment and power of young adults crafting it all makes Cry Havoc a compulsively watchable theatre.

More than that, though, as Bim says with a smile, “[The teens] are a little more fearless…much more open to both the process and to being vulnerable as both actors and creators onstage. So it’s a lot of fun.”

To learn more about Cry Havoc Theater Company and keep in the loop on their upcoming works, visit cryhavoctheater.org.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Rhiannon Ling.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.