A Foreword by the Editor

Thirty years ago an essay was published in the Canadian journal Theatrum entitled Care To Dance Dramaturge? The Invention Of A New Craft, authored by two dancer-choreographers and a dramaturg: Denise Fujiwara, Tama Soble, and DD Kugler. This pioneering document was one of the first case studies describing the working processes of dance dramaturgy, around the time when this “new craft” was just emerging. (In Europe around the same time, at the beginning of the 1980s, Raimund Hoghe, a dramaturg working with the Pina Bausch–led Tanztheater Wuppertal, was publishing his rehearsal diaries in German.)

Toronto Independent Dance Enterprise (TIDE) was the driving force behind the formation of the role of the dance dramaturg in Canada. The choreographers’ collective included Darcey Callison, Denise Fujiwara, Sallie Lyons, Paula Ravitz, Tom Stroud, Tama Soble, and Allan Risdill, among others. During its eleven years of existence (1978–89), TIDE created thirty-two collaborative choreographies. From time to time the collective invited artists they wanted to work with. One of them was DD Kugler, dramaturg and director, whose work with TIDE in 1986–87 was some of the earliest work by a dramaturg in dance in Canada.

The essay below is a documentation of Kugler’s work with two TIDE dancer-choreographers, Fujiwara and Soble, describing their experiences and articulating their processes.

When reading the recollection of their work together, it is striking how clearly Kugler, Fujiwara, and Soble articulated their new processes when there was hardly any discourse available on this topic or vocabulary for the so-called new dramaturgy to fall back on. (The term new dramaturgy was coined in the early 1990s by Flemish dramaturg and theorist Marianne Van Kerkhoven.)

Kugler came from text-based theatre as a director and dramaturg, “eager to learn from a dancer’s process,” and “curious about the entire evolution of each piece.” He, therefore, approached the “material” (the “dance text,” as he called it) in a similar way to the “material” (text) for script development. Whether he was aware of it or not at the time, Kugler was employing Eugenio Barba’s approach to dramaturgy, who in his 1985 essay, The Nature Of Dramaturgy: Describing Actions At Work, drew similar parallels between the dramaturgy of text and movement, arguing that in both cases it is concerned with the “texture,” that is, the viewing together of the material (“actions”).

When working on this new field of dramaturgy, Kugler converted the tools used in new drama development and reinvented them for the purposes of developing dance pieces. For instance: finding intentions behind even abstract gestures to make them more potent–something one would call “actioning” in text-based theatre. Or: writing a “script” for a dance performance that helps understand the “journey”–thus introducing a notion which will be later described as “soft narrative understanding” by dramaturg Katherine Profeta. With the help of these tools, Kugler then articulated “a through line, a series of emotional and intellectual connections.”

It is also striking that the question they identified as the focus for the work–”What is this gesture/movement/phrase/dance is communicating?”–is the core question of dance dramaturgy ever since.

Although the European roots of dance dramaturgy are well discussed and researched, other artists and thinkers who around the same time were moving in a similar direction are undeservedly overlooked. The thirtieth anniversary of this relevant publication provides a good opportunity to bring this important essay back into our common knowledge and shared understanding of dramaturgy, not only because of its landmark status in the history of dance dramaturgy but also because its valuable contribution to the discourse is still very valid today.

—Katalin Trencsényi

Denise Fujiwara in her work Great Wall, 1988

Photo by Cylla von Tiedemann, courtesy of Dance Collection Danse

In 1987, freelance director and dramaturg DD Kugler worked closely with two Toronto Independent Dance Enterprise (TIDE) choreographers. Artistic Director Denise Fujiwara asked him to assist her with Scratch, a solo about a bag lady for Danceworks 50 (June 1987). Tama Soble and he reworked Bang Bang, a solo dance on the theme of violence, danced by Kim Frank, for TIDE’s choreographic showcase, Making Waves (November 1987). In preparation for TIDE’s formal concert (April 1988), Kugler helped to further develop two works originally presented in Making Waves: Fujiwara’s Great Wall, a solo about personal and aesthetic tensions, and Soble’s Good People, a piece about an aggressive sales relationship, danced by Darcey Callison and Allen Norris. Theatrum asked each of them to describe a process they now call dance dramaturgy.

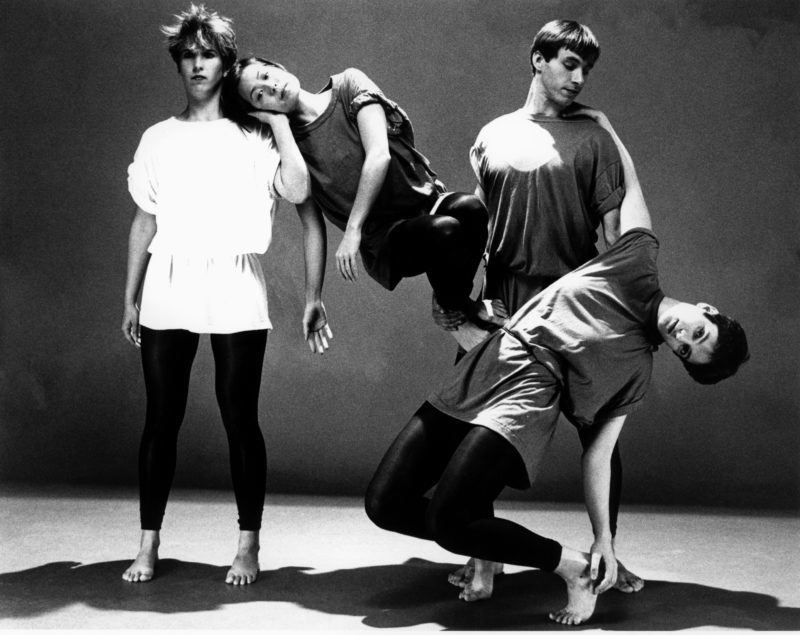

Paula Ravitz, Allan Risdill, Denise Fujiwara and Sallie Lyons in Making Waves, mid-1980s, courtesy of Dance Collection Danse

DENISE FUJIWARA

Denise Fujiwara

photography by Denise Grant

Dance is by nature abstract. Choreographers use as their tools: spatial relationships, gesture, rhythm, muscular tension, and release. Ideas and inspirations may be written down and structured, but in the end, those ideas must always be translated into movement.

Material for a piece of choreography is often born out of a particular state of mind, a stream of consciousness not terribly conducive to memorizing long and complex movement in detail. Movement is ephemeral; it must be captured and saved immediately.

As a solo artist, I found this a difficult aspect of the creative process. Details of the movement slipped away and were gone before I was able to recreate them. This is one of the reasons I wanted to work with a theatre director. I needed someone who could help me “capture” the ephemeral dance, develop the fleeting products of my improvisations, understand, recreate, and use them artfully and effectively in choreography.

When Don Kugler first came in to work with me on Scratch, I showed him a draft of the piece. It was roughly choreographed, partially improvised, and loosely structured. I was finding the subject matter, the plight of a bag lady, extremely difficult to deal with. As choreographer and dancer–the equivalent of playwright, actor, and director–I was having difficulty “seeing” the work. I needed an outside eye, a theatre mentor to help me develop the character, an editor, and a director. I didn’t know what a dramaturg was (and I still don’t), but Don played all those roles for me.

Don helped me to clarify the structure of the piece by asking me to articulate clearly my intentions and throughline. This was difficult. I found myself struggling to verbalize what were previously nonverbal ideas. These ideas were expressed in image, energy, muscle tonus, and motion. I struggled to explain, with some logic, a piece born out of intuition. He zeroed in on the places where I was unclear, and by asking more specific questions, led me to find more clarity. He never imposed his own ideas but facilitated a situation where I could create my own.

Once this was done, he looked at the piece in sections, in phrases, and finally, in the way I performed specific movements. At each of these stages, he looked at the action to see if it supported the throughline. Sometimes we changed the movement or created additional movement to fill holes in the throughline.

At times, the movement was clarified by changing the intention or the thought behind it. Just as there are any number of ways to deliver a line in a play, there are different ways to perform a phrase of movement. As a choreographer, I strive to create works where each movement “speaks” to an audience. Working with Don, I learned to define specific intentions behind movement that appeared too general or too abstract. His skills helped me use the power of the intention behind movement more effectively to help my choreography “speak.”

Throughout the creative process, Don challenged me by asking questions that I attempted to answer through the choreography. He created a supportive environment which allowed ideas to emerge and evolve. He helped me to organize the ideas that came intuitively into the structure of the piece. He was objective when I was subjective, and logical when I was intuitive.

Is this what a dramaturg does? If so, the dramaturg can play a significant role in helping the choreographer to create more potent dance.

TAMA SOBLE

Tama Soble

photography by Brenda Spielmann

As a choreographer interested in communicating emotional and intellectual content, I had begun to feel the limitations of the dance medium. Although my works evolved from a specific theme, and the performer(s) worked accurately from one physical moment to the next, this did not always translate into specific information for the viewer. I wanted to understand how to work from one theatrical moment to the next while maintaining the emotional and visceral impact that dance can generate.

To this end, I asked Don to act as theatre director for two of my works. Before starting each rehearsal process, we met and he asked me to describe the work from beginning to end, in as much detail as possible. The transcript of this discussion became a flexible script. The script was very useful to me. First of all, it was concrete: I could check the constantly shifting landscape of the dance against it, changing the script of the dance where appropriate. Second, it reminded me of the stages within the linear development that I was interested in exploring and the weight that individual sections theoretically might have. This script was drafted, redrafted, and eventually discarded as the dance took on its final shape.

Once I had mapped out a physical sketch of the dance, Don began working with the performers. He would ask what a section of the dance was intended to convey, I would describe my intentions, and he would begin. He worked the performers from one physical moment to the next, suggesting images they might use, moving around them in the space to trigger various responses, and generally helping them to find a specific subtext. I began to understand how to work with an image or idea so that it would go beyond merely motivating a performer, and begin to read to an audience.

It was also important to address the differences in rhythm between dance and theatre. In general, because dance timing deals with continuity of motion, it is quicker than theatrical timing. As Don and I worked with the performers, choices had to be made as to whether the kinetic flow should be slowed or accelerated in order to support the theatrical life of the dance. Choices were made based on each individual situation. For me, the issue of how to blend the rhythmic life of theatrical and kinetic moments remains a complex challenge.

After working with Don on one dance (Bang Bang), the type of preparation that was necessary on my part, in order for him to work efficiently with me and the performers, became evident. I found that it was best for him to come into the studio when my ideas were already fully formed. This enabled him to approach the movement as a concrete and flexible entity, as I imagine he might do with a script.

Realizing the parallel between script and movement, Don suggested that he was working not as a director, but as a dramaturg. This dramaturgical input has helped me to keep the dances alive through an extended run. Understanding each moment in the dance, from both a kinetic and a theatrical point of view, gives the performers landmarks which result in the dance having fluid stability.

Finally, introducing a theatrical perspective into my rehearsal process has allowed me to come a step closer towards my goal of making dances that not only are successful from a choreographic point of view, but that communicate specific emotional and intellectual concepts to an audience.

DD KUGLER

DD Kugler

photography by Greg Ehlers

Denise and Tama approached me for help with the theatricality of their dances. In time, I understood their need for help in a transition from abstract dance toward a more communicative content, but I began completely naïve, eager to learn from a dancer’s process. Looking back, I find it was a very good starting point for any dramaturg.

I was curious about the entire evolution of each piece. I encouraged both choreographers to talk about their source materials and to describe in detail the working units of the dance itself. I listened and took notes. Then we attempted to articulate a throughline, a series of emotional and intellectual connections which accumulates a larger content.

After I observed the dance several times, we met again and I talked through the form of the dance, isolating moments serving the content, and questioning other, apparently unrelated, moments. In this session, I attempted to compare the dance I saw with the dancer’s concept. The discussion identified goals for the dance, and strategies which might best achieve them, helping make an intuitive process more conscious. The choreographer who consciously understands the intuitive emotional and intellectual life of each moment can make more informed movement choices. These choices support, moment to moment, the dancer’s path inside the larger theoretical shape; they also allow the audience to make the journey with them.

As I became confident in my understanding of the aims, the method of working, and the needs of the dancers, I took a more active role in rehearsal. I asked the choreographer detailed questions, trying to understand the energy, shape, focus, and emotional necessity of each movement. Each rehearsal was a reassessment and reaffirmation of our shared understanding about desired content and its most effective form.

The dance “text,” which exists only in the bodies of the dancers, permitted the luxury of instantly evaluating various solutions. It’s a far more immediate process than working with playwrights from one draft to the next. The condensed form of the dances (all under fifteen minutes) made the development process, from conceptual discussion to performance, more apparent. Sharing four complete working relationships in the succession invited reflection on the process itself.

We considered a variety of titles–theatre coach, assistant director, assistant choreographer, director–for the program credit, but none of them accurately described my role in the process. It came as a surprise to realize I was working in dance as a dramaturg. The choreographer is both playwright and director; movement vocabulary replaces the written text. Dance dramaturgy has helped me better understand the dramaturg’s role in development.

To be simplistic, the creative process has two distinct parts. In the first, the artist releases a private constellation of intuitively associated images, ideas, and emotions. In the second, the artist consciously evaluates and shapes that material. If the conscious framework is imposed on the intuitive process too early, art often lacks depth and complexity; yet without conscious revaluation of the intuitive material, art may be too personal to allow a larger resonance. Every artist somehow merges these two aspects of the creative process; it does not require a dramaturg. At best, the dramaturg facilitates that secondary, conscious creative process by helping to articulate intuitive content, and helping to shape appropriate form.

The dramaturg’s goal is to give artists more conscious control over their intuitive creative process by helping them understand their own vision more fully. Artists are not innately uncritical, but it is difficult to see the whole shape clearly while you are inside it. The dramaturg, standing outside the artist’s intuitive process, supports the artist’s conscious process by asking challenging questions which lead to a clearer understanding of the artistic vision. Oskar Eustis, dramaturg at Washington DC’s Eureka Theatre, identifies a “basic underlying principle that you must challenge everything; that any time you are working on form and content you are constantly trying to re-explore and redefine their relationship to each other in a way that would express them more perfectly, more appropriately, more beautifully, especially for the specific time or place in which you are working.”

This function and method are the same in theatre and in dance. A dramaturg facilitates, through supportive challenge, the fuller realization of the artist’s conscious creative process, questioning to help the artist discover and fulfill the demands of an intuitive

vision.

Denise Fujiwara is a recipient of the Toronto Arts Foundation Award for International Achievement in Dance. EUNOIA, a multimedia work based on Christian Bök’s award-winning book of poetry, premiered at Harbourfront Centre’s World Stage in Toronto, was nominated for three Dora Awards and named one of NOW’s Top 5 Dance Shows of 2014. It continues to tour. Her most recent works include Waiting For Bardo(t) for SiNS Dance and Moving Parts, a work for singing dancers and moving choir for Toronto’s DanceWorks. She teaches Butoh and improvisation in Toronto and abroad. https://www.fujiwaradance.com

DD Kugler is a freelance dramaturg in theatre and dance, and the first Canadian president of Literary Managers and Dramaturgs of the Americas (2000–2002); in 2011, LMDA presented Kugler the Lessing Award for Career Achievement. Kugler taught for twenty years in the Theatre area of the School for Contemporary Arts at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver.

Tama Soble was a professional choreographer and performer for two decades. She has co-owned Esther Myers Yoga Studio in Toronto since 2004, where she teaches adults at all levels of practice, and administers, and is primary faculty in, a 750-hour and a graduate teacher training program. Tama also leads workshops and retreats across Canada, in the US, and Italy. She is co-author of The Power Of Touch: A Guide For Yoga Teachers, available through her website, https://www.estheryoga.com.

Notes:

- Denise Fujiwara, DD Kugler, and Tama Soble, Care To Dance Dramaturge? The Invention Of A New Craft, Theatrum 11 (Fall 1988): 17–20. The editors would also like to acknowledge the work of Sierra Carlson, who digitized the original article for this online edition.

- The original 1988 article used the French spelling, with an “e” ending. Since the role of the dramaturg originated with Lessing (a German author), at TTT we tend to use the German spelling of the word, without the “e;” hence the title of the re-published article reflecting this editorial decision.

- Eugenio Barba, The Nature Of Dramaturgy: Describing Actions At Work, New Theatre Quarterly 1.1 (February 1985): 75–78.

- Profeta, Katherine, Dramaturgy In Motion: At Work On Dance And Movement Performance (Studies in Dance History), University of Wisconsin Press, 2015, p.52.

- Dramaturgy At The Eureka: An Interview With Oskar Eustis By Mark Bly, Theater 17.3 (Summer/Fall 1986): 7–12.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Denise Fujiwara, DD Kugler, and Tama Soble.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.