Never at risk of being run of the mill, Chelfitsch — which took its name from a baby’s pronunciation of the English word “selfish” and usually stylizes itself with a lowercase “c” — is one of Japan’s foremost contemporary theater companies, despite only rarely performing here. Instead, it can mostly be found revealing the real state of today’s Japan to sellout audiences worldwide with a passion unique among its peers.

However, the company’s popularity is such that wherever it performs — from Lebanon to Croatia, the United States, China, Brazil and beyond — the audience usually includes a few itinerant Japanese theatergoers, with lots typically turning up for the world premieres it often stages in Europe.

But without trading in Orientalism, manga or samurai swords, how has Chelfitsch gained such status since its 2004 debut with Five Days in March — about a couple’s five-day sex-fest escape from ugly reality as the Iraq war started in 2003 — at the Kunstenfestivaldesarts in Belgium?

The key to this Tokyo company’s success is likely the top priority its 45-year-old founder, playwright, and director, Toshiki Okada, gives to ensuring everything it presents is a contemporary mirror of our world designed to reach as wide an audience as possible.

Now, at last, Japanese theater lovers without long-haul pocketbooks have a chance to see what all the global stir is about when Chelfitsch’s latest work, Pratthana — A Portrait of Possession, opened on June 27 at Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre as part of the Japan Foundation Asia Center’s Asia in Resonance 2019 event.

The fruit of a three-year collaboration between Okada and Thai author Uthis Haemamool, together with Thai actors and theater staff, this four-hour work, whose title Pratthana (Desire), is based on an autobiographical novel by Haemamool.

Following its world premiere in Bangkok in August 2018, the play wowed audiences and critics at the Centre Pompidou in Paris that December, where it was a headline program in the Japonismes 2018 exposition of Japanese arts and culture that ran for several months in France to mark 160 years of the two countries’ diplomatic relations. And so now, finally, to Ikebukuro.

After opening in 2016 in Bangkok, Pratthana catapults its hero, Khao Sing, to the 1990s when he was an art student at university. It then traces his life back to its starting point via various military regimes, populist and mainly corrupt civilian governments and periods of constitutional democracy, before the May 2014 takeover by a military organization called the National Council for Peace and Order.

Against a backdrop of such dramatically turbulent times in Thailand, the play also traces its protagonist’s frustration, bafflement and anger — and his way of coping through an unrestrained sex life and debates with friends and lovers.

Oddly enough — but perhaps not so considering this is Chelfitsch — although the company has performed in countless countries, Pratthana is Okada’s first-ever co-creation in Asia.

Explaining this, he says,

“We have survived so far thanks to warm financial and artistic support from several European theaters and organizations. However, I never believed that would continue forever because it stemmed from a leaning to cultural diversity over there — and we now see all that’s being shaken.”

Just as clouds began gathering in Europe, though, Okada attended a talk Haemamool gave in Tokyo in 2015 about censorship in Thailand. ” Actually, I wasn’t so interested in Thailand but wanted to know his situation as an artist working under those conditions,” Okada says. “As a fellow artist, I couldn’t treat it as having nothing to do with me.

Then, after he heard that Haemamool was writing a novel about his life titled Silhouette of Desire, the two began to collaborate to dramatize it, with Okada writing the script and directing the resulting play, Pratthana.

“A key thing is that this play is based on a work written by a Thai author for people in Thailand,” Okada says. “Sure, you might say Dostoyevsky was writing for Russian people, but those novels are now our common treasure, and I’m not interested in dramatizing world literature like that. Instead, I want to make theater about localized things that are actually happening now, but which we hardly realize or just pass by in our busy lives.”

In particular, Okada says he is especially interested in creating plays that take audiences outside Japanese society — or those based on that society that he can present to audiences overseas who know little about the reality of contemporary Japan.

Regarding the latter, since 2016 Okada has been commissioned by the state-funded Munich Kammerspiele theater to stage original plays about today’s Japan. Performed in German with German actors, these have proved popular and have drawn high praise.

“I think theater works effectively take and sublimate minor but important topics to a wider, more universal scale of artworks,” Okada says. “So whereas reading is quite a personal method of enjoying a story, once I render the same story into drama and people can see the play together with lots of others, then the communal experience creates a tension in the theater space and produces something magic, I believe.”

As a result, he says that although nothing in Pratthana has fundamentally changed between Bangkok and Paris and Tokyo — “the outcome is always different because the nature of the audience is different.” For instance, in France recent demonstrations by the yellow vest protesters have been big news, while issues from Okinawa to harassment to high heels have been bringing Japanese people out onto the streets.

So what does Okada want to tell audiences in Tokyo through this Thai artist’s story?

I want to show tensions between the state and the people. I think this is a very contemporary global issue.

This play strongly reflects today’s situation in Thailand, and through its episodes we can see problems caused by that tension much more clearly than in a story about Japan or a Western country.

So because Khao Sing has seen such chaos and contradictions up close, audiences can experience that, too. In fact, they could regard this play as a possible future for their own society.

Despite that, Okada is keen to stress how it is not his aim to answer the questions he poses in his play, insisting that is a task for each individual audience member.

“I have always been interested in ‘divided society’; it’s my eternal theme,” Okada says. “However, I’m not saying how we should solve that. I just show the complicated consequences of a divided society as vividly as possible. That’s my work.”

For this production, though, Okada handed the set design, art direction, and choreography to Yuya Tsukahara, leader of the Contact Gonzo performance troupe.

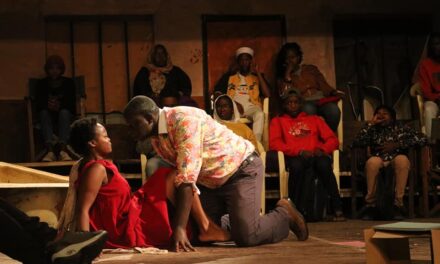

Certainly, the apparently violent movements he introduces at times brilliantly conjure an atmosphere of threat reflecting the social context, while the play’s 11 Thai actors take turns in the part of storyteller, with all of them always on stage along with technical staff such as Tsukahara, the sound designer, lighting designer, and costume designer.

This play presents a rare opportunity to experience the work of one of Japan’s most elusive dramatists without traveling halfway round the world to do so.

Pratthana — A Portrait of Possession ran from June 27 to July 7 at Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre. It was performed in Thai with Japanese and English subtitles. For more information, visit precog-jp.net/tickets or asia2019.jfac.jp/en.

This piece first appeared on The Japan Times and was reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Nobuko Tanaka.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.