The Edinburgh Festival Fringe has, over the years, developed a reputation as a hotbed for alternative, edgy, and controversial performance. Graham Main’s Blood Orange is no exception. The play is a seething dramatization of the supposed rise of the far right in Scotland. But as someone who has done years of research on the far right in Scotland and beyond, I found Main’s premise flawed.

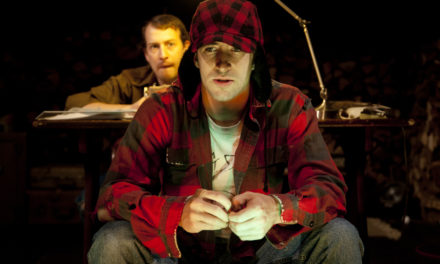

The plot centers on a vengeful, murderous pact between a disillusioned young man and a hardened neo-Nazi, following a chance encounter. The play deals with some important themes in understanding the far right. In particular, it captures the significance of personal experiences, the influence of manipulation, and the desire for belonging that feature in conversion stories.

The play was written after the theatre company, Electric Theatre Workshop, attended a Scottish Defence League (SDL) demonstration in Dumfries in May 2013. The SDL are a far-right street movement, whose agenda centers on challenging what they see as the “Islamification” of Scotland.

Armies of the Far Right?

There were actually only about 50 SDL members in attendance at this demo, accompanied by four times as many anti-racist protesters. But the play paints a picture of many hundreds arriving by the busload from the north, while “an army” is expected from Tyneside. Although a degree of artistic license is permissible, Main’s production vastly inflates the reach of this group in Scotland. The SDL have only ever managed to mobilize 100 to 150 members (and more commonly ten to 20). Compare this to the English Defence League’s (EDL) largest demonstration, which took place in Luton in 2011 and attracted an attendance of 3,000 people.

Historically, the far right has been weak in Scotland. While some may rush to attribute this to Scotland’s purported egalitarianism, the truth is less comforting. A lack of organized far-right activity does not signal the absence of racism, prejudice or bigotry. The Defence League model – which involves recruitment among football casuals – hit a stumbling block in Scotland. Here, sectarian tensions run high between the Catholic-aligned Celtic and Protestant-aligned Rangers football clubs, whose fans account for around half of all Scottish football support.

This division seems unassailable, even with the hysterically touted threat of “Islamification” looming large. As well as sectarian divisions, existing national identities and projects in Scotland tend not to align with the Defence League agenda, which is disposed toward a particularly English form of Britishness. So, contrary to Main’s premise, it seems clear that the SDL began life as a largely spent force, and has rumbled along at a low and angry ebb ever since.

A Lack of Charismatic Leaders

In the play, the character of Mole depicts the strong and charismatic leadership of the SDL – the organization described throughout as a “fascist regime,” while its members are “skinhead Nazi scum”. Anyone who has followed the trajectory of the SDL will spot two major issues with this characterization.

First, a key reason for the failure of the group, relative to their English counterpart, seems to have been the lack of such a figurehead. The EDL’s ex-leader Tommy Robinson was the charismatic founder, leader and official mouthpiece of the organization. It was around him that the EDL rose, and without him that it is now ultimately falling. The SDL, on the other hand, is composed of a self-appointed central committee and a small number of fragmented individuals.

Second, the description of the SDL as fascist or Nazi is, I believe, misguided. While there is a small number of members in the SDL who subscribe to extreme right and fascistic ideologies, the majority of supporters tend to be disillusioned, confused, and inactive. Main’s liberal use of the swastika throughout the play highlights his attempt to compress the SDL into the iconoclastic infamy of National Socialism.

The value of political theatre is clear, and efforts to explore the far-right, and racism more generally, are to be commended. Yet Blood Orange seems to lean toward oversimplification and sensationalism. If the company’s intention is to provoke anti-racist responses, then more power to them. But the extreme and violent neo-fascism portrayed in the play does not typify the SDL or other forms of Scottish racism.

Rather than growing in Scotland, the far right has struggled to get a foothold and remains terminally unstable. Opposing racism in Scotland involves examining and challenging ingrained inequalities and everyday forms of racism, which are not as obvious targets as the tattooed, skin-headed boot boy. Part of the problem is that structural inequality, bigotry, and banal racism aren’t as morbidly exciting to write about as their violent variant. And this is ultimately the rut that Blood Orange seems to fall into.

This post originally appeared on The Conversation on August 14, 2014, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Ruari Shaw Sutherland.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.