The first notes of Simon McBurney’s production of Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute) which opened on May 19th at The Metropolitan Opera begin before the house lights have gone down. We watch as visual artist Blake Habermann rhythmically writes the name of the show and act on a blackboard which is projected in real time onto a scrim across the stage. Tamino (Lawrence Brownlee), and the Three Women stumble through the audience and past the orchestra before reaching the stage. The pit, helmed by Nathalie Stutzman has been raised so the musicians are in full view and closer to the action. “Pay attention!” everything seems to shout. Despite the mystical and somewhat convoluted plot (which includes snake slaying, freemasonry rituals, and of course enchanted instruments) this show will not be a departure from our world into another. Rather we should understand the world on stage as an extension of our own. This is our world but better, a world striving for “beauty and wisdom”.

Flautist Seth Morris and bird puppeteers in Die Zauberflöte at The Metropolitan Opera PC: Karen Almond

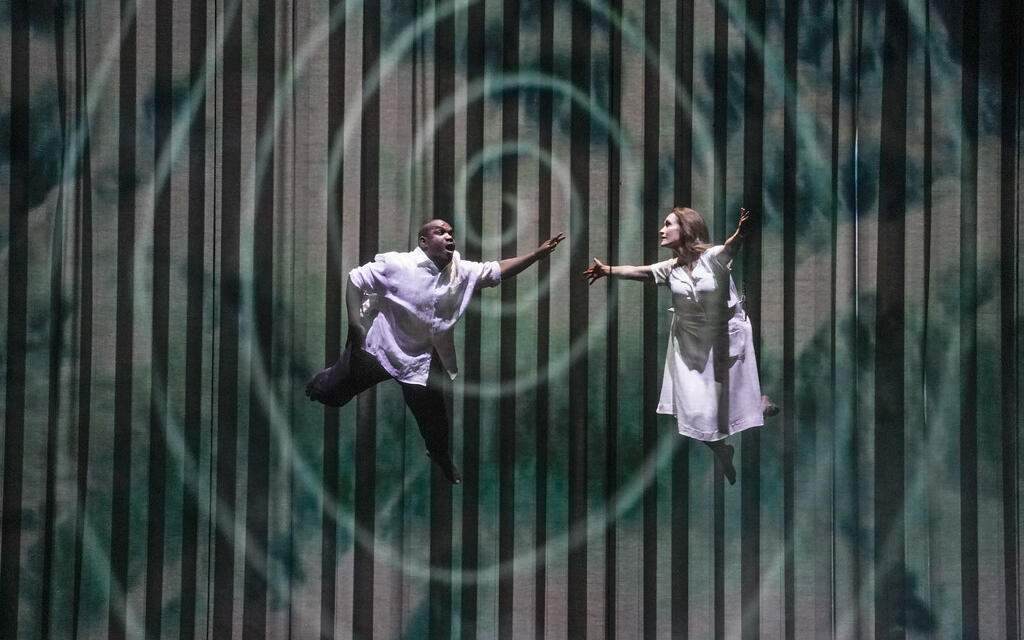

In contrast to the dazzlingly bright puppetry of Julie Taymor’s production (which will remain in The Met’s holiday season next year) the charm of McBurney’s Zauberflöte comes from finding magic in everyday things. Pieces of paper are magic! In the hands of talented puppeteers and occasionally members of the orchestra, they become Papageno’s birds. A shelf of books is magic! Habermann arranges the tomes to become Sarastro’s temple of wisdom. Even a bottle of urine is magic, but I won’t spoil that one! Michael Levine’s set is visually simple, consisting mainly of a single platform that transforms from a book, to a wall, to hill and more through shifts in height and tilt. Likewise Nicky Gillibrand’s costumes are unassumingly pedestrian, bordering on drab. The exception being the colorful garb of Papageno (Thomas Oliemans) and his papa-paramore (Ashley Emerson).

Already enthralled with the meanings and whimsy afforded to the mundane, I was curious when the Met’s go to Queen of the Night, Kathryn Lewek, arrived onstage with a cane. I grew a bit nervous when, at the end of her first aria, O Zittre Nicht Mein Lieber Sohn, she sat down in a wheelchair and was met with scattered laughter. After a bit of research I learned that the wheelchair has been a part of the production since it was developed in 2012 for the Dutch National Opera. McBurney spoke about the choice in an article for The Guardian a year later saying, “She says she’s losing her power. But then she goes on to sing one of the most demanding arias in opera. So if we’re to treat what she says seriously, the question becomes how do we physically show her growing powerlessness? I thought the wheelchair would do that. By the end of the opera, she can hardly move.”

Granted this quote is from 10 years ago and his intentions behind the choice may have changed, but the fact that he said it, and the wheelchair itself, remain. This is an example not only of disability being used as a metaphor (rather than a generative, nuanced experience in its own right), but the most tired, blatantly ableist metaphor available. Without a trace of shame McBurney confidently asserts that disability equals “powerlessness”. Never mind that most wheelchair users associate their chair with more freedom, more strength, and more ability to to participate in the world around them.

Kathryn Lewek and Erin Morley in Die Zauberflöte at The Metropolitan Opera PC: Karen Almond

And then, just to further entrench this insulting narrative, at the end of the show the Queen’s adversary Sarastro (Stephen Milling) makes peace with her and she gets up out of her wheelchair. Plenty of people are ambulatory wheelchair users meaning they sometimes use their chair and sometimes walk with or without a mobility device. What I take issue with is not that she stands up, but that standing up is necessary to her redemption (to the extent that it’s granted). In order to enter Sarastro’s new world of light and reason she must leave her chair behind. At the beginning of the second act, one of the priests of Sarastro’s temple asks Tamino what he seeks and Tamino replies “a better world.” At its core, that’s what Die Zauberflöte is about– the pursuit of a better, more harmonious future. Whether he intended it or not, what McBurney has presented makes it very clear that this “better world” does not include disabled people.

More often than not if disabled people find themselves represented in theater at all it’s as either a victim or a villain, objects of either pity or fear. This iteration of the Queen of the Night is both. Another typical option is the wise, mystical sage, but don’t worry, that trope is also represented in the form of the three guiding spirits (Luka Zylik, Deven Agge, and Julian Knopf ) who are played by children dressed as old men. The gimmick here seems to be how odd and funny it is to see children using canes, as if such a thing could never occur in real life. I find it somewhat depressing that such tired tropes could be reiterated on a stage as large as The Metropolitan Opera, one of the world’s foremost cultural institutions.

The irony is, the production’s innovative approach to technology actually holds a lot of potential for creating fully accessible performances. Finn Ross adds computer-generated projections and we watch artist Blake Habermann write out stage directions and scene titles, why not extend this to projected supertitles? This way the text is not just on a separate, isolated screen, but artistically incorporated into the whole viewing experience. (Artistically projected captions were recently used to great effect in Ryan Haddad’s Dark Disabled Stories at The Public where the size and amount of text often punctuated jokes and arguments.) The sound design by Gareth Fry includes about 100 speakers scattered throughout the house. This creates a playground for live Foley artist Ruth Sullivan who immerses the audience in the sounds of birds, brooks, and thunder. What if these localized speakers were also used to project audio description to a certain floor or section of the theater?

Thomas Oliemans and Ruth Sullivan in Die Zauberflöte at The Metropolitan Opera PC: Karen Almond

If one is really interested in exploring disability in The Magic Flute story there are more interesting places to look than the Queen’s “powerlessness”. If we consider a mobility device not as a symbol of weakness but rather as an object that empowers freedom of movement, might we imagine the enchanted instruments which guide Papageno and Tamino on their journey, namely the magic flute itself, to be such a device? What if Papageno’s bells were attached to wheels that rang out as he rolled himself to true love? What if Tamino’s flute doubled as a cane? I don’t know if any of these ideas are possible or what their full implications would be, all I know is that more creative engagements with disability are not only possible, but necessary.

To his credit, McBurney at least attempts to destabilize the blatant sexism of Emanuel Schikaneder’s libretto. On its surface the text characterizes the feminine as chaotic, overly emotional, and evil and pits it against the supposedly morally superior rationality of man. As McBurney has configured it, the tale is less gender essentialism, and more a quest of young lovers seeking independence from parental figures, struggling with how to trust themselves and each other in a world of moral grays. Erin Morley even manages to get a bit of a quiet strength out of princess Pamina’s somewhat pathetic suicidally lovesick material.

I believe McBurney has virtuous intentions. Reflecting on this year’s production he said, “society should evolve. What kind of society are we moving towards?” and “How do we transform the consciousness of the audience—or the consciousness of society, for that matter?” Of course, I agree. Society should evolve and I believe art can play a powerful role in how we “transform the consciousness of (…) society”. I wish McBurney had taken this responsibility more seriously by not falling back on tired tropes and harmful stereotypes of disability. In this production Zauberflöte’s last number, “Schönheit und Weisheit” (beauty and wisdom) serves as a moment of reconciliation where the Queen is reintegrated into the community by giving up her wheelchair. I, like Tamino, seek a better world. But I, unlike McBurney, hope it is one where the wisdom and beauty of disability leads the way.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Morgan Skolnik.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.