Based on 136 play The Cabal of Hypocrites by Mikhail Bulgakov, with additional texts by Pierre Corneille, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Molière, Jean Racine.

Frank Castorf’s reputation precedes his creations. The director-monumentalism is known for his epic adaptations of the western literary canon and innovations in stage design, specifically the use of film on stage. Die Kabale der Scheinheiligen lives up to its reputation. It presents a full range of Castorf’s directorial palette. Even if the six-hour theatrical marathon might feel a little over-stretched – do we really need a clown routine with a chair for another 20 minutes? – the play is something to be experienced live at least once, and definitely here, at the Avignon Theatre Festival.

The story of this colossal production is based on the life of Jean-Baptiste Poquelin, Molière, his complex relation with King Louis XIV and the Catholic Church, his personal affairs, his theatrical triumphs, and his fall orchestrated by his enemies, all of it as imagined and told by the Russian-Soviet writer, Mikhail Bulgakov.

Bulgakov’s novel is often interpreted as an autobiographical metaphor, the writer’s attempt to explain his relationship with the state, and his life of internal exile, when he lost all means of income, possibilities to work or publish any of his writing. The legend has it: Stalin took a special pleasure in taming the author. By making a personal phone-call to Bulgakov, he promised him freedom of exile – so he would be issued his foreign passport and a visa to finally leave Russia – if the writer behaved. The result was Bulgakov’s attempt to write a dramatic biography of Stalin’s revolutionary career, a still-born play of his literary genius, conceived under the pressure of survival.

All this information, distorted and fragmented, shattered and over-extended by many other inter-textual references, including Racine’s Phaedra and Fassbinder’s Beware of a Holy Whore, among others, make the kaleidoscopic landscape of Castorf’s dramatic narrative, visually reflected in a similarly kaleidoscopic staging.

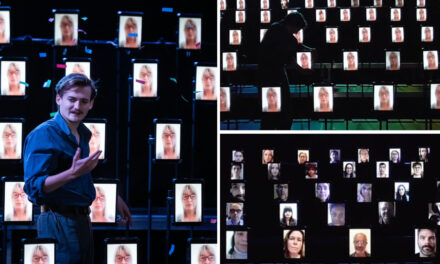

Die Kabale der Scheinheiligen is presented in Avignon’s Parc des expositions, a famous venue in the region where corporate events, inaugurations, theatre and trade shows, artistic and commercial exhibition are organized. This major venue presents a circular arena/exhibition area of 27 500 square meters, all made fully available for Castorf’s enterprise. The audience is located in a frontal arrangement with three different pavilions or stations included in the staging. The movement of the stations is reminiscent of the popular French street theatre just before Molière’s time, its mode of production (the flourishing of small touring companies) and its favorite genres, such as farce and satire, to which Molière was also the rightful heir. Each station presents a different location: the first one is the home of Molière that is also his theatre, a two-story theatrical platform/wagon that transforms into a stage, a bedroom, and a tavern. The second one is the King’s alcove with an enormous bed inside it, which will later turn into the death-bed for Molière himself. The last one is a sitting room, serving as the off-stage place for actors to rest, or for the King’s adversaries to plot against Molière and his company. The rest of this enormous facility takes on many other fictional locales, as envisioned by the director and his designers.

The major device of this staging is the use of a live-camera that follows actors onto off-stage spaces and inside the stations, with the close-ups of their faces projected on a large screen. This famous device – known yet in the traditions of the Czech Laterna magika, with the actors jumping off screens on stage interacting with their own filmed images projected onto the screen – is Castorf’s special signature/style. In Die Kabale der Scheinheiligen the filmed and the enacted scenes are intertwined, which creates an effect of alienation and vertigo. At times, the action fully moves onto the screen: we see actors working in the far-off spaces of this showground and at the same time watch them life-streamed. The effect of temporal simultaneity – another Castorf’s famous device – is produced by our being able to observe the work of the camera-crew, the actors enacting the scene off stage, and its projection streamed centre-stage at the same time. Occasionally, Castorf makes the actors on stage interact with the audience and with other characters/actors projected on screen, all at the same time, as moving through a certain scene, staying in character.

However, what was extremely innovative a decade ago, today reads as a somewhat tired device. Perhaps, if the balance between the video and live acting was made a little more even, which does happen in the second part of this show, the audience would stay as spellbound as it used to be with Castorf’s previous productions.

The acting, however, is simply superb. Switching between German, French, and English, the performers keep their characters intact. A demanding play, with lots of physical comedy, numerous improvisations, character changes, and stage distances the actors must cover in seconds by running across this massive space, all this adds to the complex psychological nuances the performers must play, when it comes to enacting Bulgakov’s intricate characters.

The sense of theatricality – life on stage in the spotlight, under the surveillance of cameras and spectators’ watchful eye – reigns over Die Kabale der Scheinheiligen. Indeed, what else can be there for an artist, whose life and work have become a personal interest of his monarch. The artist and the state is one of the most pertinent themes of Russian literature. In Castorf’s performative reimagining, it comes fully alive through the mastery of dramaturgical deconstruction and through the brilliance of theatrical technology, which brings theatre’s oldest machinery into a creative dialogue with its newest forms. Vive Molière! Vive le Théâtre!

Reposted with permission from CapitalCriticsCircle.com

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Yana Meerzon.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.