As a young French director visiting New York with his theater troupe, Paul Desveaux hardly expected to fall in love with an American painter’s work one afternoon on a trip to a museum. Even more remote was the possibility that in 20 years, he would return to New York to direct his own production about that same artist. Yet further from his mind was the idea that this original French theater piece would be presented in English, and brought to life in part thanks to the French Embassy.

But this is precisely what transpired.

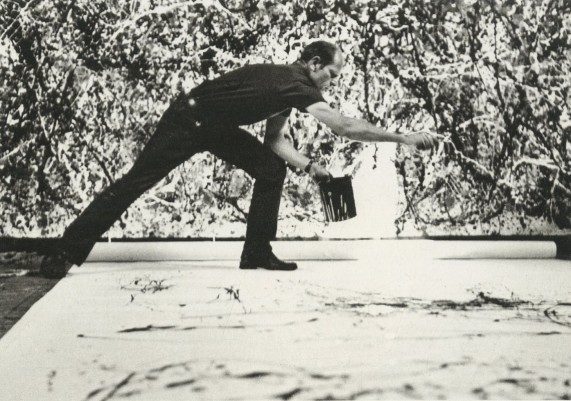

The year is 1998, and Desveaux has just experienced a coup de foudre for Jackson Pollock’s paintings. The place is the Museum of Modern Art—the first retrospective in New York since the one mounted by MoMA in 1967—and Desveaux’s eyes are stretched open wide, drinking in Pollock’s immense compositions, vibrating colors, and chaotic drips.

©Oeuvre Magazine

The year is 2008, and Desveaux commissions a script from Fabrice Melquiot, the oft-awarded playwright, poet, novelist, and director who had already had two of his plays presented in the U.S.—in San Francisco and Chicago. Melquiot’s musical phrases and colorful imagery seem well-suited to a story on Pollock and Krasner. And who better than Melquiot—who Desveaux proclaims to be un écrivain-voyageur—a writer-traveler—to author this French ode to a slice of America?

Together, Desveaux and Melquiot agree that their production must work towards redeeming Krasner’s largely forgotten career as an artist and set out to reveal the challenges she faced in the male-dominated art milieu.

Once the duo has agreed upon a text, the French production embarks on a successful tour of France. Next, Desveaux sends a statement of intent to the Cultural Services of the French Embassy in New York, expressing his desire to have the play adapted in English for an American audience. “Nicole Birmann-Bloom and Rima Abdul-Malak responded within 48 hours,” reports Desveaux today.

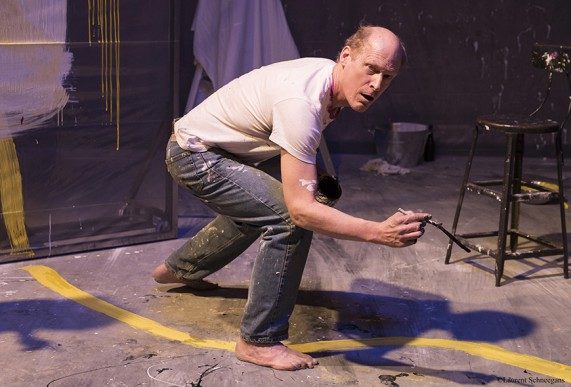

©Laurent Schneegans

The play’s translation is then entrusted to Miriam Heard and Kenneth Casler. The French and English languages—with all of their phonetic differences—phrasing, nasality, elision—read differently on stage. In the words of Desveaux himself, “[…] American English […] is more physical, maybe more carnal.” To his delight, the two actors playing Krasner and Pollock in the 2018 edition—Birgit Huppuch and Jim Fletcher—internalized the intended rhythm immediately. And this rhythm is buoyed by Vincent Artaud’s original music—a mix of Bebop and Hard Bop—composed especially for the play.

A live reading of the English version of the play at 972 Fifth Avenue, the Cultural Services’ headquarters, takes place, in December 2015. This is followed by a reading at Abrons Art Center, which immediately gives the show a green light.

What came out of this international collaboration was a “tactile, kinetic, carnal” production—“a surreal sparring match steeped in alcohol and dripping with paint.” Pollock is portrayed as “alcoholic, brilliant, violent” and Krasner is “creatively ambitious” and “nurtures his tattered psyche” (The New York Times). Acclaimed for its acting, translation, and stage direction, the play was praised by French and American press alike.

Pollock, a tribute to the eponymous artist and his wife, brought to life by two talented actors disguised as “barefoot ghosts” (The New York Times), will continue its tour around the United States. Stay tuned for show dates.

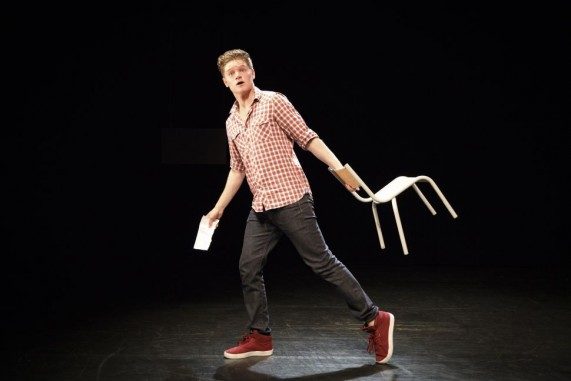

©Laurent Schneegans

For the past several years, the Cultural Services of the French Embassy has focused on exporting the rich French contemporary theater scene to the United States. Unlike plays produced in Anglophone countries, French pieces harbor the unique challenge of their language—a challenge that often hinders a play’s ascension to the international scale.

The work of the Cultural Services in this domain includes two primary objectives: supporting tours of French productions in French with English subtitles, or French plays translated to English—as in the case of Pollock.

It is advantageous to put on a French play in English for an American audience as subtitles are typically an immediate deterrent for theatergoers. This also allows the producers to work with American actors, whose names can pique the interest of audience members and attract viewers who might not otherwise have been drawn to the production. Not to mention that the more languages a play is available in, the bigger its audience becomes.

The motivations for exporting French theater are also in part humane. Viewers get a lens through which to glimpse—maybe even better understand—another culture. And the crew, cast, producers, writers, and director gain an opportunity to create bonds with their counterparts across the Atlantic, while steeped in the whirlwind experience of putting on a play.

©Laurent Schneegans

The Cultural Services accomplishes this second mission through various means, including facilitating the translation of a play, organizing auditions, raising funds, connecting French theater teams to American presenters, organizing the first readings at the Cultural Services, and assisting with the coordination of the whole production process. These efforts are supported by the Cultural Services’ own vitally important partners, including SACD, Institut français, FACE Foundation, and the French Ministry of Culture.

The Cultural Services has thus accelerated the translation and production of five plays over the past three years: Oh Boy! (Olivier Letellier); In The Solitude Of Cotton Fields (Roland Auzet/Bernard-Marie Koltès); Even Knights Get Forgotten (Gustave Akakpo/Matthieu Roy); Dough (David Lescot), and Pollock.

The Molière Award-winning Oh Boy!, about coping with adversity as a child, directed by Olivier Letellier, adapted for the stage by Catherine Verlaguet, translated by Nicholas Elliot, and performed by Matthew Brown, is based on a book by Marie-Aude Murail of the same name. Thanks in part to the Cultural Services’ involvement, it premiered in January 2017 at the Duke Studio on 42nd Street, presented by The New Victory Theater.

And Bernard-Marie Koltès’ classic In The Solitude Of The Cotton Fields, a play that follows a late-night negotiation between a client and dealer, while addressing themes of power, violence and humanity, premiered at New York University’s Sense Of Sound symposium, with Oceana James and Tory Vazquez, thanks to support from to the University and the Skirball Center for Performing Arts. It was recently re-staged for the all-night marathon of philosophy talks, music, film screenings, and performance art, A Night Of Philosophy And Ideas with Oceana James and Dee Beasnael.

©Oh Boy!

More plays are being prepared for the American stage still. The Girl, The Devil And The Windmill, based on Brothers Grimm’s tale and directed by former Festival d’Avignon director, Olivier Py; To The Heart, by Linda Lê, directed and choreographed by Thierry Thieu Niang; Silence and Fear, by David Geselson; and Art du Theatre by Pascal Rambert, and Snow, a theatrical adaptation of Orhan Pamuk’s novel of the same name by Blandine Savetier and Waddah Saab.

This article originally appeared in French Culture and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by French Culture .

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.