In 1943, Dolia Ribush, a Russian-speaking Latvian theatre director of medium height and considerable charm, made an illegal trip to Sydney from Melbourne — interstate travel at that time, as during Covid-19, being restricted.

Ribush’s aim was to persuade Australia’s leading poet to collaborate on a stage play. His ally in this endeavor was the critic A.A. Phillips, a close friend, and the business manager of his theatre company, the Ribush Players.

The poet in question was Douglas Stewart. In 1942, his verse drama Ned Kelly was broadcast by the ABC as a radio play. Ribush was convinced it could be adapted for the stage.

He won over not only Stewart, but Stewart’s admirer and supporter, the artist Norman Lindsay, who agreed to design the show.

Thus in October 1944, exactly 11 years before Summer of the Seventeenth Doll appeared in the same venue, Ned Kelly opened at the Union Theatre on the campus of the University of Melbourne, in a production that involved some of the country’s most accomplished and self-consciously Australian artists. Phillips, still six years shy of publishing his influential cultural cringe essay, was in the production, taking the part of an anguished preacher, Reverend Gribble.

Although the play’s season was short, it had a profound impact on those who saw it, including a 16-year-old schoolboy named Manning Clark. Twenty years later, the historian wrote to Rosa Ribush, Dolia’s widow, saying

one of my sources of inspiration to write “A History of Australia” was seeing the production of Ned Kelly. It was an event in my life which made me pose the question: why are we as we are? … In moments of despair, and they happen all too often, my mind takes comfort from recalling that night in Melbourne when your husband’s work got me thinking about what Australia stands for.

An Undervalued Play

Ned Kelly is one of the most undervalued plays in the national repertoire. In part, this stems from its seemingly passé look as a verse drama, a genre which enjoyed a modest revival in the 1930s and 1940s. So its radical sensibility is easy to miss.

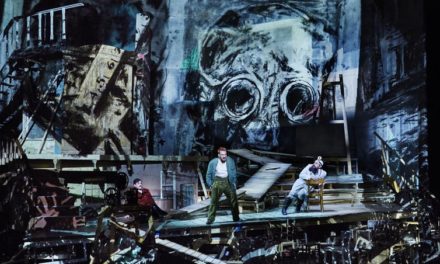

In 1997, I directed Ned Kelly in one of its few professional productions. Spruiking the show to audiences, I heard many times that people “already knew the story.” But when I asked what they knew, they were often at a loss to give even the basic facts. They felt they knew the Kelly story, but they did not.

This combination of belief the past is known, and actual ignorance of it, fuels Australia’s “history wars.” Stewart’s play thus falls into a historical black hole as well as a theatrical one.

A nation dismissive of its past dramatic forms is also dismissive of its past. Reclaiming Ned Kelly is therefore about more than its disinterment from the sarcophagus of neglected plays; it is an act of intellectual recovery whereby Australian history is made available as a dramatic resource, and drama is validated as a mode of historical inquiry.

Grandeur and Violence

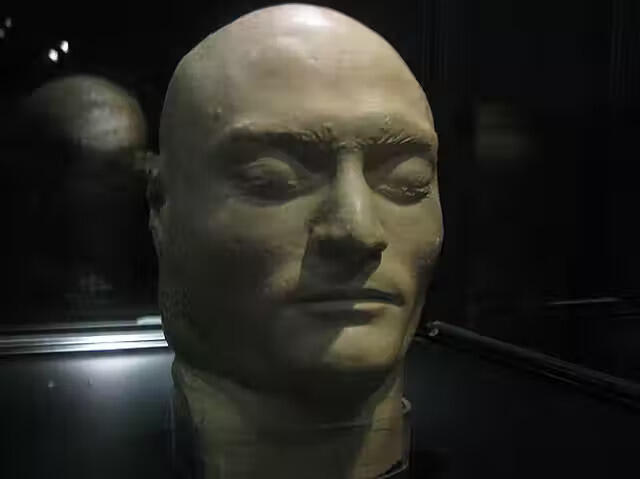

Douglas Stewart (1913-1985). Fryer Library.

Ned Kelly has a feature unusual in drama, but not uncommon in great poetry: the more you read it, the more disturbing it becomes.

Presented in four acts, at a time when three was the norm, the play is epic in scope. Its long speeches vary between descriptions of the vast emptiness of the bush and exhaustive examinations of the morality of the bushranger’s deeds.

Even today, these deeds prompt divided responses. For some Australians, the Kelly gang were cold-hearted killers, who deserved their bloody end. For others, they were victims of the historical injustice inherent in the convict settlement and its legacy of colonial repression and abuse.

The fact that Ned Kelly and his brother Dan were Irish by blood and background is also important, evoking the exploitation of Britain’s first colony, Ireland.

The language of the play is incomparable. Grand and sweeping, rather than stylish and urbane, it eschews realism for a larger poetic effect. Stewart’s rhythms anticipate Patrick White’s in The Ham Funeral (1961), Season at Sarsaparilla (1962), and A Cheery Soul (1963). Like White’s, his view of humanity is discomforting, at times even chilling.

Though little is shown in Ned Kelly and much is said (in keeping with its origins as a radio play), violence drips from every page. This is not the reassuring redemptive violence of melodrama, where villains get their just deserts and heroes walk into an upbeat future. It is an unholy crush of hostility, brutality, and slaughter that covers the action like an ash cloud.

In Stewart’s vision, it is as if violence is stitched into the Australian national character. This is voiced directly by Reverend Gribble in speeches of turbulent, agonized power.

Act One is set in the country town of Jerilderie, where the gang hold up the bank and corral the population in the pub, threatening to shoot the bank manager until the preacher intervenes:

Laugh at me if you like,

That’s better than brooding murder. When you laugh at the bar

It’s hard to imagine those terrible shots in the mountains,

The cries, and the blood on the ground, and on your hand …

In England even the words, the fields, and the rivers,

Like the churches the Normans built, ivy and stone,

Have a sense of grace and order, a long tradition

Of labour and love and patience against the weather.

Australia’s the violent country, the earth itself

Suffers, cries out in anger against the sunlight

From the cracked lips of the plains; and with the land

With the snake that strikes from the dust,

The people suffer and cry their anger and kill.

I have come to understand it in love and pity;

Not horror now; I understand the Kellys.

Like the fall of the House of Atreus in Aeschylus’s Oresteia, the end of the Kelly gang is foretold. A supernal doom haunts the play, not least because Ned and his fellow bushrangers know they are going to die.

This imparts a dense, almost unbearable claustrophobia to the action. Despite the gang roaming over miles of bush, the emotional terrain they occupy is cramped and ever-reducing. As they run out of time, they run out of space. Queensland dangles the promise of escape, but it is an illusion. The gang isn’t going anywhere but the graveyard.

Irony, ambiguity, and amorality create the play’s compelling mood. All the characters, with the exception of Ned Kelly himself, behave in a self-interested way. It is as if moral judgment of the gang’s actions were unimportant, something that changes depending on who is in charge or how many drinks have been downed.

Ned tries to act out of conviction. But he lives in a colonial society with little integrity, so his resolve to be a man of principle leaves him even more isolated than the murders he commits. The play ends with the famous image of Ned Kelly in his armour, fighting the police, an outcast because of his defiant attitude as much as his murderous deeds.

A Fundamental Change in Australian Theatre

1942 was a signal year for Australian drama, and produced an extraordinary flowering of playwrights, including Dymphna Cusack (Morning Sacrifice), George Dann (Fountains Beyond), Max Afford (Lady in Danger), and Douglas Stewart (Ned Kelly). It must therefore take its place as one fundamental change in Australian theatre.

The 1950s, which saw the premiere of Summer of the Seventeenth Doll, is often seen as the watershed decade. Yet the 1940s were decisive, in both enlarging the kinds of drama that playwrights wrote and the capacity of their plays to convey complex philosophical, political, social, and psychological insights.

Not only did Australian drama grow in professional craft, but so did the cultural imagination of the nation it addressed. Significantly, this new growth — Phillips would have said, new maturity — occurred not at a time of collective confidence, but when Australia was at its most vulnerable, troubled, and alone.

That the challenging experience of war should give rise to a consolidation of our national drama is a profound indication that it is more than an exercise in confirmation bias, echoing views and values we already hold. Drama is a powerful engine of collective discovery that, in 1942, achieved new heights of expression, when the country’s circumstances were at their worst.

This is an edited extract from Australia in 50 Plays (Currency Press).

This article was originally posted to The Conversation on March 16, 2022, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Julian Meyrick.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.