Virginia Woolf’s reputation has closely followed British cultural trends: in the interwar years she was a beacon of modernism, austere and difficult; by the 1970s a feminist icon; in the 1990s a cultural and social snob who disparaged servants and the poor; and today a symbol of the history of woke. Her most politically charged book is not Mrs Dalloway, with its picture of upper-class London life, but Orlando: A Biography, her 1928 fantasy epic about gender fluidity. This filmed record—streamed online on 22 April—of the stage adaptation, written by Alice Birch and directed by Katie Mitchell for Berlin’s Schaubühne, is a contemporary exploration of identity and desire.

Orlando is born into the Elizabethan era. As a rich nobleman he becomes a teen favourite of the aged Queen Bess. Writing poetry in his spare time, he falls in love with Sasha, a Russian princess, and has his work mocked by the critic Robert Greene, then, the best part of a century later, in the bewigged Restoration era, he visits Constantinople and, in a transformation scene, becomes a she. For the next 250 years or so, Lady Orlando holds court in London, and enjoys love affairs with people of both sexes, while embracing once again the literary life. She finally marries Marmaduke Bonthrop Shelmerdine, a gender ambiguous sea captain.

The original book was inspired by Woolf’s love affair with Vita Sackville-West. As Jeanette Winterson says, “What Vita and Virginia did or didn’t do in bed is much less important than the effect of Vita on Virginia’s imagination.” Clearly Woolf’s sense of fantasy was set free by this experience and her novel is deliciously written, partly magic realist, partly seriously poetic. Mitchell sees it as the “first English language trans novel” and this adaptation is both faithful to the original’s flights of exalted writing and rather disappointing in its staging.

As usual with this director, Mitchell creates a live film event out of her staging, with actors and crew creating scenes on the ground which are then projected onto a big screen high above the action. The screen allows wonderful close-ups of the actors, in this case mainly Jenny König in the title role, with the other performers barely getting a look in. The projected scenes are intercut with some pre-filmed outdoor episodes. This method is more or less the same as many of Mitchell’s previous shows, pioneered by her brilliant version of Woolf’s The Waves in 2006, and it effectively illustrates how reality, and in this case gender identity, is constructed. We literally see it being made and re-made in front of our eyes.

The problem, however, is that this is all there is. On the plus side, Birch’s edited distillation of the novel preserves some of Woolf’s vigorous dialogue and several of her flights of imaginative description, with their inspired cascades of animal metaphors and musings on melancholy, literary creativity and the inevitability of death. On the minus side, despite the frantic efforts of the cast, the show’s projected images are usually banal and visually uninteresting. Close ups of the piece’s narrator, situated in a glass box on the top right of the stage, are an example of this mundanity: basically, this is just a projection of a woman talking into a microphone.

Mitchell’s trademark use of deliberate anachronism, scattering cars, air planes, anti-Brexit demos, modern underwear and tampons across the centuries—with Greene appearing as contemporary hipster—adds little to the either visual or cerebral delight, and tends to distract from the occasional powerful image: projections of a dead dog and a doe giving birth are powerfully metaphorical. Likewise, there are some moments when the poetic beating wings of desire or rushing waters of heightened emotions come across perfectly. Sadly, the orgy scenes and shagging are stilted and unerotic.

This is a shame because the essence of Woolf’s views about gender fluidity remain markedly relevant. Orlando effectively explores our anxieties not only about our gender identity, how we feel in our bodies, but also our feelings about the Other. What does it feel like to be a member of the opposite sex? And how would it be to experience both a male and female body? How fluid is desire? Gender, of course, is a performance, and this is the strongest aspect of Birch and Mitchell’s version. Here we see not only abstract ideas, but can experience the sensations of desire, disgust and disillusion.

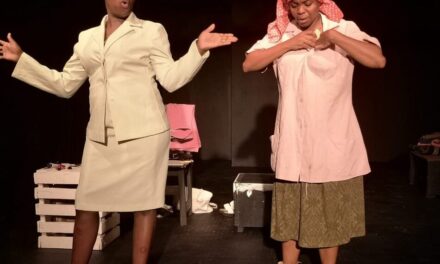

The queer sensibility of the story is shouldered both by König, who is marvelously expressive in her startled looks which alternate with world weariness and quizzical gestures (in her close ups, she gives a knowing look to elicit audience complicity), and by the rest of the underused cast, who cross dress and strip off with amusing alacrity. On Alex Eales’s set, the richness of the text is supplemented by extravagant costumes. As filmed by Carsten Woike, however, the experience is quite frustrating: much of the delicate lighting disappears and the action is sometimes lost in gloom.

But that’s the thing about filmed theatre: it too often fails to capture the thrill of being at a performance, and this is certainly true here: the spoken words are much more interesting than the visual images. One longs in vain for a stronger editorial hand. It is also disappointing that the Schaubühne has not exactly been generous in its decision to stream Orlando for one evening only—compare the practice of London theatres which make shows available for weeks rather than hours. Finally, the saddest aspect of this Orlando is that while Woolf’s original proved its radical point by being innovative in form and content, Mitchell’s version offers nothing new. In fact, all that she proves is that woke is the new conformity — and surely the conventional is always stifling.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.