February 15, 2019, Café Markov, Tehran, Iran

Sāmān Arasṭoo is an Iranian actor and theatre director, born in 1967 in the city of Shahrud, Iran. He is the founder of the Āvā -ye Dīvānegān Theatre Group (آوای دیوانگان), which translates as Music of the Crazed. He has battled with gender issues his entire life and experienced a forced marriage in 1991, which soon ended in divorce. In 2008, Arasṭoo underwent sex reassignment, which shifted his approach to theatre, as he began to focus more on the awareness of gender issues onstage, especially with regard to the LGBTQ community. Arasṭoo’s purpose became to guide transsexuals and to provide a space of acceptance. In early 2015, he established “transsexual workshops” or “self-awareness workshops”, which offered a platform to explore not only one’s sexuality but also one’s individuality and innate nature. His most recent performance is entitled “Kālbodshekāfī”, or Autopsy, and was performed in the Sayeh Black Box Theatre, in Tehran’s City Theatre, from January 9 to February 7, 2019. This performance not only served as an educational resource for those audience members unaware of the LGBTQ community but also successfully explored gender and identity issues. I had a short chat with Sāmān Arasṭoo at Markov Café in Tehran, about his general work objective and his most recent play, Autopsy. Autopsy is a scriptless play, performed with the mere use of white cloth as a shroud, a belt used for a few scenes that demonstrated violence, and a red lipstick that the actors would ask random audience members to put on for them. Apart from the mentioned items, there were no additional props or scenery designs. The performance aimed to draw more attention to words than to visual stimulation. The content of the play would change nightly, as the actors performed solely on improvisation. Actors would emerge from their shrouds (white cloths covering their bodies) and, upon completing their improvised dialogues, would submerge back into their dark and isolated space. Arasṭoo discreetly provided direction as to when the actors should commence and end their dialogues. Apart from the director, Sāmān Arasṭoo, himself, Autopsy starred Nādīā Bāvand , Hedīeh Khānīān, Hamīdreżā Sangīān, Mānā Sharīfīān, Sīmā Shokrī, Māhī ‘Aẓīmī, Morteżā Alīdādī, Meysam Ghanīzādeh, Hamīdreżā Ghobādī, and Amīrmo’ayad Bāvand.

Farinaz Kavianifar: Let us begin with the general manner of your productions: please elaborate on your establishment of the Āvā -ye Dīvānegān (Music of the Crazed) Theatre Group, in 1987.

Sāmān Arasṭoo: Cell Number 18 was my first work. The group was initially called Chakāvak (Lark), which I then renamed Āvā -ye Dīvānegān (Music of the Crazed). In the early years, we worked on Euripides’ Medea and Sophocles’ Antigone but without the use of texts. I’m not a believer in using texts in theatre. I chose Greek texts because I believe that Greek ideologies transcend their inscribed dates and that such works can be universally applicable. I searched in the works of Sophocles, Euripides, and later Lorca for deep societal issues that one faces globally. I became more active in the 1990s and 2000s, before my sex-change operation, in which I worked on a few of Esma’īl Hemmatī’s plays. There was a play called Four Hands which was classified as children’s literature and was not a particularly great work. Everyone asked why I selected this piece for performance, but I believe that one needs to have the skills of making lemonade out of sour lemons! I revised the text and turned it into a dark play for a mature audience. I had three editions to this play, one which was performed for children, one for young people, and one for adults.

Āvā -ye Dīvānegān (Music of the Crazed) has also worked with scripted texts, but ones that, as a director, retouched and revealed the societal elements that were my primary desire of focus. For instance, the original playwright of the production would often come to my performances and would feel a difference in the work. although no particular dialogues were missing. It’s not a director’s job to merely work on a text from a to z, as this is neither original nor is it creative.

F. Kavianifar: How have your initial goals and intents for Āvā -ye Dīvānegān (Music of the Crazed) changed and shifted over the years?

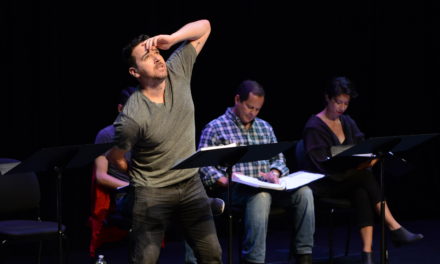

Autopsy. Nādīā Bāvand pulls out of her shroud (of identity), running towards the audience to express her frustrations and concerns. Photo by Babak Haghi.

S. Arasṭoo: I began my hormone therapy in 2006 and worked on two plays at that same time. One work was a traditional Iranian piece, The Wedding of Malāyer’s Ruler with Shāh Parīyān’s Daughter, in which I dressed all the female actors in men’s attire. It was the only performance in the ongoing years of the Fadjrheatre Festival whose viewing was restricted to women only; men weren’t allowed to attend this performance. I began protesting and gained a lot of media coverage until I was finally granted a public showing in the Sangelaj Theatre, a location reserved for traditional and ritualistic plays.

After sex-change surgery, I intended to work on bringing awareness to some parts of my life. I began to write, and during that time, I did another showing of the traditional play that was previously performed in the Sangelaj Theatre, and another piece on war, titled Forbidden Territory.

In 2013, I had to re-establish my group once more, as some of the actors were migrating to the West and others were no longer interested in performing in theatre. In 2014, All of You Know Me was performed. It’s quite challenging working with me, as there’s never a set time or date for when a piece will go onstage. A public performance might happen in a year, or it might never be performed at all. Our team does not strive or work to achieve a public showing.

F. Kavianifar: None of your performances are scripted, and the content of the performances are solely based on improvisation. Can you please explain how you prepare actors for the stage?

S. Arasṭoo: I provide challenges for the actors and push them to engage in discussion. I don’t like to say that I employ actors; I employ individuals. Someone who comes on to my stage is a person who has experienced a great amount of upheaval. Our practices are challenging because the actor is forced to confess to his or her most personal and intimate events. Often, the actor breaks out in violence and hysteria. In one rehearsal, we had someone who would punch a hole in the wall because that individual had to confess to things he had never discussed publicly.

One has to dissect oneself because, without that self-dissection, one can’t really explore or get in touch with one’s character onstage.

As for the criteria of employment of actors, I require the individual to be crazy, careless, fearless, soulful, and to encompass trust both in themselves and in the director.

The techniques used onstage are closely interwoven with theatre therapy. The question that gets raised is on the issue of existence. Our practices are extensive and intense, and I work on breaking down the individual. It is that catharsis and ripening that is seen onstage. Since the performances revolve around improvisation, the dialogues are fresh, and the actors do not feel jaded or exhausted after a few showings.

F. Kavianifar: Can you please explain how you utilize theatre as therapy and a medium between the actors and the audience?

Autopsy. In the first act, Sāmān Arasṭoo aggressively pulls on the hair of Morteżā Alīdādī, in order to cause some distress and discomfort for the audience. The rest of the actors stay at rest under their shrouds. Photo by Babak Haghi.

S. Arasṭoo: From the initial moment, we strive to make the audience uncomfortable. They are never left alone; we stage a disturbing scene previous to the commencement of the play, and once they enter the black box theatre, there is no peace or darkness, as the lights are shone straight into their faces. We remove the safe space and put them in the spotlight.

The theatre is therapy. There’s no need for theatre to deliver a specific message. The audience has to reach a point of self-identification with the events occurring onstage. When this happens, they forget that the man onstage is a transsexual because the events that the man is talking about relate closely to their own lives. In Sīmā and Mānā’s scene in Autopsy, a lot of audience members approached me afterward and told me that they related to that particular scene. Theatre allows one to engage in discussion. When you see your own life onstage you became more comfortable discussing it. I work on breaking the taboos of society; it is okay to be shy, embarrassed, or frightened.

F. Kavianifar: How much of your performances can you say is a result of a personal catharsis?

S. Arasṭoo: All of You Know Me is an exact replication of my personal stories apart from one section which is my experience with a friend who had undergone a male-to-female transformation. This performance became educational, and we performed for seventy-two days, operating all on improvisation. In previous years, I had offered “self-awareness” workshops[1] which functioned on the basis of theatre therapy with transgender individuals. These workshops allowed me to ripen my ideas as I noticed the similarities between the different stories. I became even more affirmed in my belief that humans share similarities in all different forms and shapes.

F. Kavianifar: You have undergone sex reassignment and label yourself as transgender, yet it seems that you try to break the structured limitations of gender and identity in your plays. Please elaborate on this topic.

S. Arasṭoo: The world revolves and advances around the concept of contradiction and ambiguity. In fact, it is such contradictions that bring meaning to life. For instance, a rose is not a rose without its thorns. I declare that I’m transgender not only onstage but outside as well. Identity is a gathering of information, a gathering of desires, and one’s innate nature. When I alter my body by means of a sex-change operation, the stored memory or information, the desires, and the innate nature do not extinguish. Thus, I’m not after an identity but in search of matching my physique to it.

In Autopsy, we go ahead and break such boundaries. Let’s have a universal vision and accept individuals just as they are, with all their faults and contradictions. It’s when we accept another’s faults that we can grow in acceptance.

F. Kavianifar: So, Autopsy is, in fact, a lesson of love and acceptance?

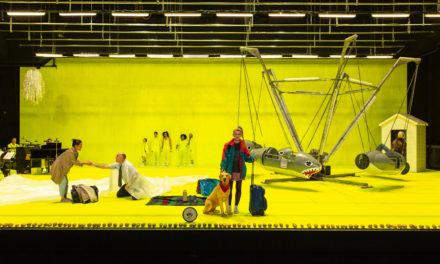

S. Arasṭoo: Definitely. There were seven actors on stage in Autopsy, five of whom were female, but these words of gender are meaningless to me, as I view these actors as separate from their sex. No individual is entirely male or female. The body’s physical composition illustrates one’s sex, but it doesn’t prove one’s gender orientation. I primarily feel responsible for educating a society that lacks knowledge of minorities, such as the LGBTQ community, and secondarily, in breaking the boundaries of identity. When I performed All of You Know Me in 2014, it was the first theatrical work on the LGBTQ community in Iran. It was performed in three different seasons without any private or governmental support or sponsorship, yet it was a hit because people were thirsty for knowledge on the subject. The goal of Autopsy is to show the audience that the actors onstage, regardless of their sexual orientation, are human beings and individuals that we might be speculating about with a subjective and judgmental eye. To give you an example, you might see a bottle as light green, but that same bottle could appear as dark green to another. Art’s purpose is to transcend all forms of limitation and create a universality.

F. Kavianifar: In that case, Autopsy can apply not only to gender issues but also to art.

S. Arasṭoo: Exactly! The poet Forūgh Farokhzād says, “You can’t compose poetry about a starving population when you are enjoying a grand meal at a dinner table.” Art creates humanity—that’s the goal! Our art is shifting towards another dimension, a dimension that’s all about materialism, fame, and red-carpet moments.

F. Kavianifar: Autopsy is an outcry of the stories of the LGBTQ community. What are the criteria for role selection? Do your actors also have to belong to this community to be a part of the performances, or can they be individuals who support your path towards and outlook on theatre?

—Autopsy. An audience member applies lipstick to Hamīdreżā Sangīān. Photo by Babak Haghi.

S. Arasṭoo: A selection of them were from the LGBTQ community, but not all. The actors are usually ones who are involved in the “self-awareness” workshops and who’ve participated in my acting classes. In Autopsy, there were two or three individuals who had just recently joined our group.

F. Kavianifar: Why did you select the title Autopsy?

S. Arasṭoo: It is a workshop for the dissection of the mind and soul, both for the actors and for the audience. We dissect the actors and the audience. Many individuals from the audience would approach me after the show and ask, “who am I?” or inquire whether I had a self-exploration workshop in which they could attend.

F. Kavianifar: Speaking more specifically about Autopsy, you use a short film about a transgender woman who resides in a park. Can you please explain why you chose to use this dialogue in the film and what was the purpose of using a filmed scene in the midst of your unscripted performance?

S. Arasṭoo: The actors appear and disappear in white shrouds onstage. Symbolically, this is trying to illustrate the isolation that these individuals experience in society. They appear, recite their dialogue, and crawl back into their dark and isolated space. The film serves the same principle. These are people who have no space to voice their concerns, and I provided them with that opportunity.

F. Kavianifar: In Autopsy, there is a transsexual man by the name of Mānā who sings onstage. What is the purpose of the employment of singing in this work?

S. Arasṭoo: The songs are from Sīmīn Ghadīrī.[2] These songs are childish, and with that said, they provide you a certain ambiance. There is a mature man who, despite his age, is still trapped in childish behaviors and thoughts. The same transgender and childish man is able to marry up to four wives and does as he wishes, but if his wife decides to divorce him, she will be slandered by society. These are some of the issues we want to bring to the attention of the audience.

F. Kavianifar: Did you face any limitations or difficulty in obtaining a permit for this performance?

S. Arasṭoo: I believe that art with limitations is one that generates creativity. An artist is responsible for crossing the boundaries of censorship and limitations in the best possible fashion without losing that which he wants to voice in his work. The words “bisexual” or “transsexual” are not used in Autopsy, but the provided symbols are enough to deliver the message of the discussion.

F. Kavianifar: What message does Autopsy strive to deliver?

S. Arasṭoo: Learn to unravel yourself; learn to be yourself.

Hamīdreżā Sangīān and Meysam Ghanīzādeh quarrel over their love affair.

Farinaz Kavianifar received her M.A. from the University of Chicago in Middle East Studies (2018) and her B.A. from George Washington University in Middle East Studies and International Relations, and a minor in Religion (2015). Her academic area of research and focus has primarily been on Persian and Arabic literature and Middle East cinema. She has always been interested in the interrelation of art with sociology and anthropology, and, as a result, she has recently immersed herself in the study and research of theatre and performance in Iran. She gave a talk at the University of Chicago’s Persian Circle in 2018, entitled “The Tradition and Music of the Yarsan”, and presented a paper at the International Conference on Arts and Humanities (IAFOR) in 2016 in the U.A.E., entitled “Appropriating Tradition: Female Empowerment through the Embrace and Reinterpretation of Religious Texts and Social Values”.

Notes

[1] Beginning in early 2015, Arasṭoo commenced a free workshop called Self-Awareness designed for transgender people and their family members. In a year’s span the workshop gained more than 150 participants. The workshops were held weekly in five-hour sessions and usually at a rented black box stage. Because of a lack of governmental and nongovernmental support, all costs were paid solely by Arasṭoo. Currently, there aren’t any workshops being held, because of financial and legal restrictions, yet Arasṭoo is still accepting and receiving phone calls to provide “self-awareness” guidance.

[2] Sīmīn Ghadīrī is an Iranian singer most notable for her music and lyrics for children. She has also sung the poems of Farhād Sheybānī, Žilā Mosā’ed, Mohammad Kīānūsh, and Ahmadrezā Ahmadī.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Farinaz Kavianifar.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.