Some news stories have a very long half-life. Their power to shock does not diminish; they continue to radiate pain. One such is the gang rape and murder that happened in South Delhi in December 2012. Jyoti Singh, a 23-year-old female physiotherapy intern, was horrifically beaten, sexually assaulted and tortured on a bus in which she was traveling with her male friend, Awindra Pratap Pandey. Six men on the bus, including the driver, were responsible for knocking him unconscious and the sexual assaults. Singh died soon after. This incident not only provoked widespread revulsion in India, and the rest of the world, but is also clearly one of the incidents behind Anupama Chandrasekhar’s new play.

Although the playwright has suggested that she was also inspired by Henrik Ibsen’s Ghosts, in which the sexual sins of the fathers infect their sons, her play has much more to do with toxic masculinity in Indian culture than with the adaptation of European classics (it has none of the compact depth of the Ibsen). Set in Chennai, When the Crows Visit is a symbolic family drama that explores the relationship between 48-year-old Hema, a widow, and her son Akshay, who is in his mid-twenties. At the start, Hema is living with Jaya, her aged mother-in-law, who is also looked after by Ragini, a young nurse, and home help. So the play begins as a comedy of manners in which Jaya and Ragini bicker and wrangle in an amusingly familiar way. But soon the mood darkens.

Akshay, who loves computer games and works for his old friend David in a Mumbai company specializing in their creation and development, loses his job after a violent incident, during which he attacks a woman, in the street outside a bar. Provoked partly by the comparative success of Uma, a female work colleague, this outburst leads Akshay to return home to his mother and grandmother. On his return, it emerges that his now-dead father was a serial abuser, violent towards women and that his son has inherited this mindset. Worse, both women were, and still are, in many ways complicit with this violence, making excuses for it, or denying that it is happening.

So the central theme of the drama is toxic masculinity in a severely patriarchal system. Chandrasekhar clearly shows not only how Jaya, representing an older generation, can turn a blind eye to the abusive nature of her son, but also how his long-suffering wife, Hema, can do the same with the young man that is her son — despite her negative experiences with the boy’s father. The playwright is careful to create Hema as an intelligent woman, charming, a touch arrogant and occasionally vulnerable. Yet when it comes to facing the truth about her son, who is likewise not a monster (even though he is capable of behaving like one), Hema is unable to cope.

On top of this picture of contemporary masculinity, red in tooth and claw, in today’s India, Chandrasekhar overlays some material which refers to a more ancient society. In one scene Akshay performs an ancestral purification ritual, in which he connects with his dead forefathers. Similarly, old Jaya is a compulsive storyteller, whose moral fables carry the power of ancient wisdom, often with a satirical twist. But the pervading image is that of the crow, which symbolizes the appearance of the sins of the father and forefathers. By amusing contrast, the play also features examples of birdlife that can only be described as pestiferous.

It has to be said that there is something very disturbing in both the play’s portrayal of male violence and in its apparent acceptance that this is somehow passed down the generations. Although there is a brief suggestion that Akshay is further desensitized by his love of violent video games, this aspect of the story is under-developed. Chandrasekhar never really questions this image of toxicity as a hereditary condition, and the complicity of female victims is not explored much either. Depressingly, while the piece is not exactly a right-wing play, it is certainly politically dubious, to put it mildly.

The main problem with Chandrasekhar’s play is that the text can’t quite decide whether it is a soft social satire or a fierce examination of toxic masculinity. It tries to be both, and that doesn’t really work. There’s an unevenness of tone, in which some characters are comic stereotypes and others have a more serious intent, and you’re never sure how seriously to take the folkloric aspects of the story. The best comic scenes are those between Jaya and Ragini, which achieve a good balance between contemporary attitudes and Hindu myth. But, oddly enough, the text-only really catches fire when Akshay gives voice to his feelings of blatant male aggression: “I felt feral, like I was inhabiting the body of a beast. I felt sleek, and powerful.”

The trouble with strong writing like this is that Akshay’s rediscovery of his inner manhood is not only unchallenged but ends up with him apparently getting away with his crimes. Okay, showing an injustice on stage can be a savage indictment of corruption and of masculinity unleashed in a patriarchal nightmare, but as theatre, it makes for pretty depressing viewing. The violence and vigor of male bravado and misbehavior is never really contested by the other characters of the play, and when Hema’s sister Kavita appears, accusing her sister of complicity in male violence, she soon departs the stage. So this is not really a feminist analysis of patriarchy; it’s more of a ruthless melodrama.

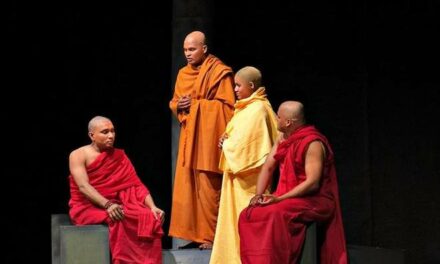

Indhu Rubasingham’s production is likewise too noisy and unsubtle to be enjoyable, changing gear between scenes with too much melodramatic acting, and not enough naturalistic exploration of emotion. Although Richard Kent’s versatile set is a good background for Matt Hutchinson’s shadow crow puppets, which feel underused anyway, the acting is uneven. Ayesha Dharker produces some moments of emotional depth, but both Soni Razdan (Jaya) and Aryana Ramkhalawon (Ragini) are more comic than the material requires. Bally Gill lends Akshay a boyish grim and a troubled brow, but his character has few redeeming features, and the other men, played by Paul G Raymond (David) and Asif Khan (police inspector and neighbor) are either underwritten or too cartoonish. In the end, despite some good passages, this is a confused, confusing and politically reactionary evening.

When the Crows Visit is at the Kiln Theatre until 30 November.

This article was originally posted at http://www.sierz.co.uk and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.