Yuval Sharon was recently awarded a MacArthur Fellowship “genius grant” for his mobile opera Hopscotch, performed in 2015 in Los Angeles. But before Sharon’s car opera was even conceived, the Iranian environmental performance Unpermitted Whispers (Najvāhāy-e Biejāzeh) awed its passengers/spectators by taking them on a journey through the streets of downtown Tehran. The Iranian female director Azadeh Ganjeh created Unpermitted Whispers in 2010 for the Shakespeare Creative Workshops section of the 13th International Student Theatre Festival and won the top award for her unique and audacious approach in shifting the borders of theatrical space and intimacy. [1] She revived the show in December 2013 for twenty nights. Each evening, from 4 p.m. to 11 p.m., the group gave four performances of approximately 50 minutes each.

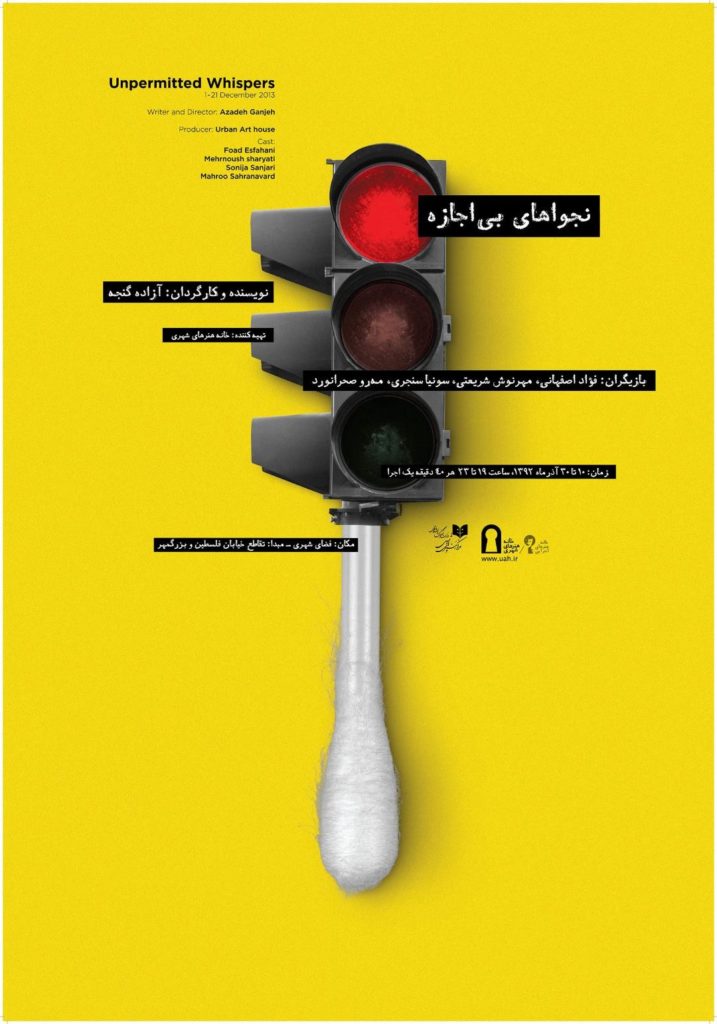

designed by Pedram Harbi, Harbi Studio

The play is performed in a taxi that is carpooling a driver/actor, an actress, and three passengers/spectators who are simultaneously waiting and are waited on by the performance crew in a nearby café. An usher guides the three spectators to an intersection, where a Peugeot taxi awaits them. The trip begins right after the spectators/passengers hop into the taxi and the first actress squeezes herself into the back seat. The taxi takes its passengers throughout a fixed route, covering about 10 kilometers of an area surrounding two major universities, the University of Tehran and Amirkabir University of Technology, located on Enghelāb (Revolution) street. Enghelāb Square and Street and the two universities have been the focal point of numerous political demonstrations and student protests throughout the last century. On its return, the taxi discharges the spectators somewhere close to the starting point. On each leg of the trip, three actors alternately enter and exit the taxi and share their stories with the spectators/passengers, and in the intervals between, the driver recounts his own memories and stories of nearby places and their events.

Two other cars accompany the main taxi, one that circulates throughout the streets to transfer the actresses, and one that is driven by the director as an escort vehicle. The cast included Mehrnoush Shari’ati, Morvareed Kheradmand, Mohammad Ebraahim Azizi, Sonia Sanjari, and Mahroo Sahrānavard; and Foa’ād Esfahāni was the directing consultant and driver in the later performances. Ganjeh’s main motivation for creating the very first Iranian (world?) mobile theatre stemmed from three questions: How can theatre connect citizens with their city? How can the creative team of a theatrical performance empower their spectators to respond actively to the unpredictability of the world around them? and How contemporary is Shakespeare for Iranian life? [2]

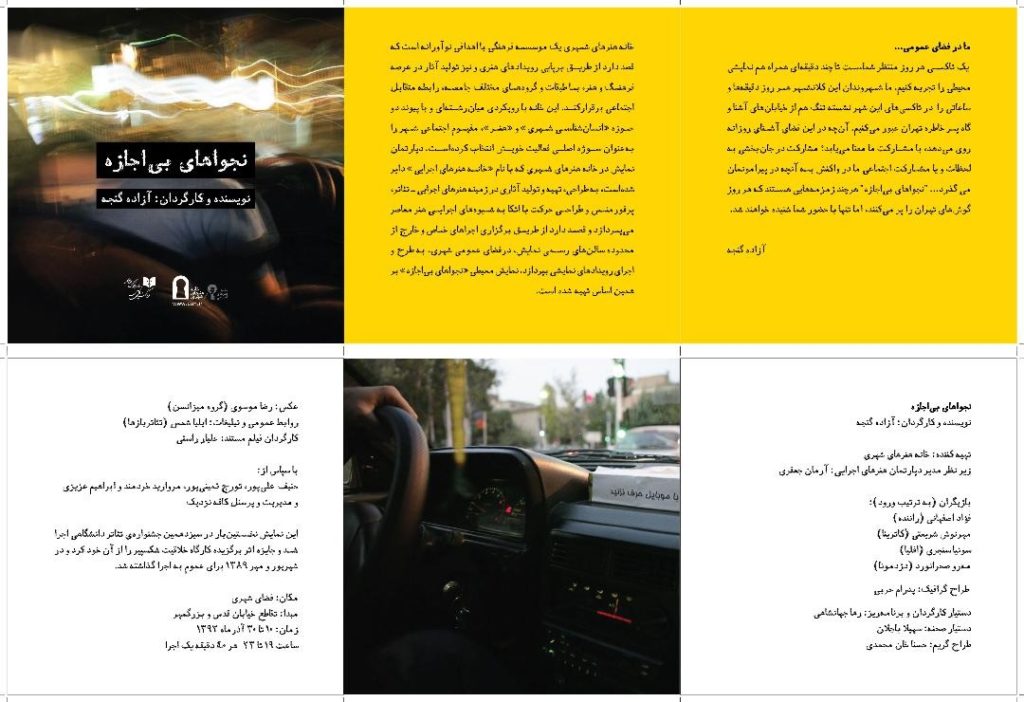

Photo: Hana Havari

The play has three episodes, each dramatizing a slice of a woman’s life, and all revolve around a shared theme (women’s familial and conjugal conflicts,) but, depending on the spectators’ intervention, it is very likely that the chain of events takes new directions. Azadeh told me that she had written three storylines for this episode based on her predictions about the scale and nature of the spectators’ potential interaction with the actress. [3] To characterize these women, Azadeh Ganjeh sought inspiration from three Shakespearean characters: Katherina, Ophelia, and Desdemona, three important but marginalized women. [4] Ganjeh, however, limits her character adaptation to their main human traits and relies more on her spectators’ choices and interactions to forward the plotline. To Ganjeh, contextualizing these three women in a modern time and place is both thought-provoking and refreshing. However, she barely goes further than using these names, and her characters’ personal stories remain only thematically faithful to Shakespeare’s women.

The first episode, which begins with the first actress’s sudden jumping onto the taxi’s back seat, dramatizes Katherina’s series of hasty and agitated phone conversations with her friend and her husband, as she tells various lies to her husband about her whereabouts and situation. For instance, a moment after she has told her friend that she is in a theatre, she tells her husband that she has taken a trip to the city’s holy shrine. The conversations gradually reveal Katherina’s two-faced and defiant personality. It appears that this fully clad woman has indeed a very liberal and transgressive lifestyle which allows her to loosen her hijab and go to the theatre!

Leaving the car, Katherina leaves her cell phone behind and puts the driver in the unwanted position of telling the same lies to Katherina’s husband. After a short while, the driver pulls over to drag Ophelia, his female friend, into the taxi. The second episode begins when the frantic and distressed Ophelia takes her place on the back seat, this time on the right side. The driver later reveals that Ophelia has lost her mind because of losing a friend, Hamlet, here Amir, who is a friend common to both Ophelia and the driver. Ophelia complains about her unsupportive family and describes her unshakeable love for Amir and reveals that he has disappeared during his military service, a claim later denied by the driver since the spectators later come to know that Amir has suspiciously disappeared during a chaotic street protest. The Ophelia episode raises some issues for debate, including the legal process of receiving the corpse, the difficulties of love for an abandoned woman, the political disappearance of students in the street protests, and the veracity of an abandoned woman’s elusive stories. All these topics set the ground for the spectators’ active participation in discussions on some urgent, forbidden topics.

The third episode begins with the appearance of Desdemona in a chador on the sidewalk trying to call a taxi. Carrying a big sack, she prefers to take the front seat, and her story begins after a quick rearrangement that places all the spectators in the back seat. Being a complete stranger in Tehran, Desdemona is anxiously searching for her husband at the hospitals of the city center. In a thick northern accent, she recounts events of domestic violence that have caused her husband’s serious head injury and her own imprisonment. As the taxi stops in front of the hospitals, some spectators/passengers decide to accompany Desdemona in her search at the hospital. The others open up conversations on the issues of domestic violence and the helpless situation of the woman; some student spectators even propose to host her at their dormitory. As this navigation seems to take a long time, the driver asks the spectators to leave the car so that he can help Desdemona find her husband. The performance ends here, leaving the spectators unsure whether they are still in the middle of the performance or not.

Photo: Reza Mousavi

In a note, Ganjeh writes, “Performing in the crowded streets of Tehran downtown is always full of adventure and unpredictability; it’s sweet but risky. The performing group must be constantly and instantaneously alert and dynamic. This requires the presence of the assistant director and stage assistants to leave the comfort zone of the backstage and get engaged in the scenes. The spectators here are spect-actors; their participation in a taxi-performance invites them to witness and intervene in the social processes occurring around them.” [5]

Performing such an audacious and interventionist mobile play in a carpooling taxi that has been every Tehrani’s lifetime experience has a defamiliarizing effect; it draws its audience to the intimate proximity of not only these three women but also the city itself, on and off the short-trip taxis. As communal sites of witnessing and participating in the heart of the city, taxis in Iran are most often safe spaces for voicing and sharing critical views on socio-political issues. On the other hand, they offer an unsought intimacy to their temporary inhabitants. The taxi is a symbolic microcosm of the city’s macrocosm. The spect-actors of a taxi theatre live and enliven both worlds and experience the liminal and fluid space between taxi and city, private and public, intimacy and strangeness.

Given that this immersive performance has been produced by the Urban Arts House, one primary and well-achieved goal has been to establish a close connection to social spaces and urban environments and to disentangle theatre from its conventional theatrical spaces. Tehran’s traffic rumbles and roars. It devours people’s time and tranquility, as the tired, short-tempered drivers risk their passengers’ safety with their sharp maneuvering and swerving. Despite the rigorous coordination among the cast and crew, the spectators do not expect the performance to begin and end at the pre-set time. The immediacy of this performance is further intensified by the inevitable flexibility of space and time and by the irresistible and exciting intimacy that the taxi commuters share. This degree of fluidity, along with the unpredictability and immediacy that the whole trip offers, is part of spectators’ unique theatrical experience. But the compelling thematic and aesthetic transgression of the show is not limited to these qualities.

Indeed, Ganjeh’s genius artistic choice in constructing a fluid audience framework is in tandem with her tactful interaction with the state’s Committee of Theatre Supervision. The fluidity which has enabled the creative team to open up new horizons of interpretation and interaction with script and performance has, however, been curtailed, albeit temporarily, by the state censorial regulations for issuing licenses for public performances. In a press interview, Ganjeh talks about the perplexity that the supervisory authorities were facing in issuing a license to a performance that lacks a fixed performance space. As such, Azadeh Ganjeh and her Unpermitted Whispers offer a prism of potential for action, interactions, and questions.

As an Iranian immigrant living in Canada, when I heard the news of the 2017 MacArthur genius grant I began asking myself: had Yuval Sharon lived in a “third-world developing” country, would he have even been recognized and praised as he is now by this prestigious and lucrative award? Yuval Sharon’s genius is undeniable, as is Azadeh Ganjeh’s originality; and the fact that Ganjeh’s work is pursuing far more urgent socio-political causes than Sharon’s aesthetic causes perhaps adds to its genuineness. But how can she be equally identified and praised when she and her group are grappling with incessant economic and professional hardship caused by various international sanctions and domestic unsupportive conditions? How can she shine while playing laylay (Iranian hopscotch) on a not very smooth, glossy playground?

Yuval Sharon’s recent mobile pieces, Hopscotch (2015) and Invisible Cities (2013), seem works of genius to the juries of the MacArthur Fellowship; but to me, they resonate with other cases of resemblance that we often find in the artistic works produced in the developed countries that happen to have previous prototypes in the works created originally in the “developing countries,” and happen to be dismissed and are doomed to be downplayed. Such occasions offer me invaluable opportunities for self-reflection: Why I have been so willing to appreciate the aura of originality elsewhere? Or am I downplaying the powerful potentials of our global world for inspirational exchange and hybridity?

designed by Pedram Harbi, Harbi Studio.

To learn more about Unpermitted Whispers, visit

https://www.theguardian.com/world/iran-blog/2013/dec/26/iran-drama-tehran-taxi

https://theatreroomasia.com/tag/unpermitted-whispers/

- As a fervent fan of Boal’sTheatre of the Oppressed, Ganjeh takes much interest in the dramaturgy of forum theatre. She has directed other environmental and site-specific plays too: Return, at the whole building of House of Artists (2013); Phone Booth, at a telephone booth (2006 & 2011),; and Hidden Half, in classes of the departments of music and theatre in the Faculty of Fine Art at the University of Tehran (2009 & 2010).

- AzadehGanjeh, interview with Mohsen Azimi, 5 October 2010, http://www.aftabir.com.

- AzadehGanjeh, interview with the author, 10 November 2017.

- These female names are culled from Shakespeare’sTaming of the Shrew, Hamlet, and Othello,

- AzadehGanjeh, “Note on the Unpermitted Whispers,” Iran Theater Official Website, 11 December 2013, http://theater.ir/fa/37515.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Marjan Moosavi.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.