Pressure on the German theatre and cultural landscape has increased significantly since the right-wing populist Alternative for Germany party won seats in parliament. The institutions have developed ways to deal with right-wing attacks – in part by joining together in solidarity.

A large banner next to the entrance reads, “Wir sind nicht Eure Kulisse” (We are not your backdrop). The theatre has draped the letters spelling out its name, “Volksbühne”, in black along with the legendary robber’s wheel sculpture set designer Bert Neumann installed on the lawn on Rosa Luxemburg Square right in front of the theatre in 1994. Above the entrance, the motto of the solidarity alliance that inspired 240,000 people to take to Berlin’s streets to protest racism in October 2018 glows in red lettering: “Indivisible”.

In staging its building, the Volksbühne is taking a stand against the so-called “hygiene demonstrations” that have sought to stoke the anger of different groups towards the government and the media in Rosa Luxemburg Square since the end of March 2020. What started with just a few protesters convinced a global conspiracy was driving the state response to the corona crisis soon attracted extreme right-wing political forces like Alternative for Germany (AfD) and the National Democratic Party of Germany (NPD), which have been fighting the state since the 2015 refugee crisis.

“We are not your backdrop”: In spring 2020, Berlin’s Volksbühne Theatre covered its sign and the “robber’s wheel” on Rosa Luxemburg Square to distance itself from the corona demonstrations taking place there, which were increasingly taken over by right-wing extremist forces. | Photo: © picture alliance/Christoph Soeder/dpa

Pressure on theatres, opera houses and museums has increased throughout Germany since the right-wing populist AfD party won seats in five state parliaments in 2016 and then in the Bundestag in 2017. The right-wing groups and actors targeting Germany’s artists and cultural institutions are diverse as the means they employ, and a multitude of anonymous hate mails, murder and bomb threats have created a climate of impending and elusive threat to the cultural landscape. Some productions specifically directed against the current shift to the right in society have even fallen victim to violent attacks. In October 2016, Kevin Rittberger’s play Peak White or Wir sinken das Volk (Peak White or We Shall Sink the People) “only” triggered AfD protests in front of the Heidelberg Theater. Shortly afterwards, an explosion took place at the Lokomotiv cultural centre in Chemnitz to stop a theatre project commemorating the murders carried out by far-right terrorist group the National Socialist Underground (NSU) from going forward. Alliance of solidarity and mobile support.

Back in September 2016, Berlin’s Maxim Gorki Theater had already targeted by far right-wing Identarian Movement, which stormed the live broadcast of radioeins and Freitag Salon (Radio One and Friday Salon) talk show in what they referred to as an “aesthetic intervention”. The extremist group’s press release called presenter Jakob Augstein and his guest of the day, Protestant theologian Margot Käßmann, “typical representatives of the left-liberal establishment” and accused them of being “narcissistic advocates of a trend that turned Germans into a minority in their own country.”

Reacting to this violation of the theatre’s much touted function as a safe space, especially for the many people from immigrant backgrounds who work there, Maxim Gorki approached the Mobile Beratung gegen Rechtsextremismus (Mobile Advising Against Far-Right Extremism, MBR) association for coaching and advice. Many theatres have since followed suit. One of the steps MBR suggests is for organizers to prominently display an “anti-racist exclusion clause” reserving their right to deny access to the venue to persons with right-wing extremist views or organizational affiliations. According to the MBR, this allows organizers to legal prosecute anyone violations and also discourages right-wing extremist troublemakers from attending events with public anti-racist exclusion clauses.

In the face of the increasing threat from right-wing forces, the German cultural landscape has come together to form an unprecedented alliance of solidarity: Signed by more than 300 art and cultural institutions, the “Declaration of the Many” was released in Düsseldorf, Hamburg, Dresden and Berlin on symbolic and historically significant November 9, 2018. It refers to Germany’s history in which “art was defamed as degenerate and culture widely misused for propaganda purposes” and signatories commit to “refusing to provide a platform for nationalistic propaganda […].”(Anti-) cultural policy

The AfD frequently uses parliamentary inquiries as an instrument of its cultural policy. In real political terms, the AfD is still largely powerless, but the party has taken to attracting publicity by attacking the financing of individual cultural institutions, probably with the aim of setting itself up as a “movement” or “alternative” in cultural policy debates. In October 2017, for example, in the Committee on Cultural Affairs, the Berlin AfD demanded the 2018/2019 budgets for three large theatres, the Maxim Gorki Theatre, the Deutsches Theater and the Friedrichstadt-Palast, be slashed, a move many called random and unjustified. Shortly before, the Friedrichstadt-Palast theatre’s director Berndt Schmidt had denounced xenophobic AfD voters in an in-house email. While this political battle was raging, hate mails and death threats temporarily shut down the theatre and 1,800 people had to be evacuated following a bomb threat.

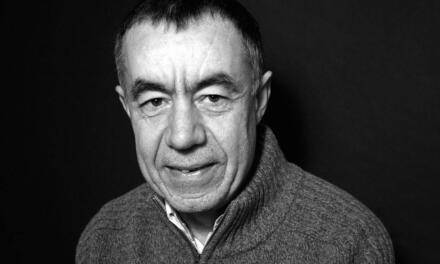

Berndt Schmidt, director at Friedrichstadt-Palast, at the press conference on the “Berlin Declaration of the Many” in 2018. 4,400 German and Austrian cultural institutions have now signed the declaration. | Photo: © picture alliance/Christoph Soeder/dpa

The minutes of the parliamentary committee meetings are all available online and some read like bad satire. The AfD has made repeated attempts to privatise parts of the existing art and cultural landscape citing the usual arguments about economic viability, but frequently attacking cultural institutions that show modern and experimental art or advocate for an open society. This was clearly an element of the row around the European Centre for the Arts in Dresden’s Hellerau the AfD kicked off in June 2019. The party insisted the building should be rented out, claiming the centre brought in too little money to finance the expensive artistic endeavours housed there. This happened one year after the new artistic director Carena Schlewitt took over and announced a new direction. The centre has also been committed to helping refugees for years.

Things had calmed down in the German theatre scene until corona hit. “The theatres and cultural institutions are involved in figuring out how to handle attacks from the right in a self-active, solidarity-based network,” Karoline Zinßer, who heads the Berlin office of “Die vielen e. V.”, explains. “Through the exchange of experience, they have put themselves in an active, formative position, gotten organized and shown solidarity. This makes them less vulnerable.” The number of German and Austrian institutions that have signed the “Declaration of the Many” has risen to 4,400 since the campaign was launched in November 2018.

This article was originally posted on the Goethe Institute on July 15th, 2020 and was reposted with permission. To see the original article click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Anja Quickert.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.