Under a busy flyover where the Island Eastern Corridor becomes Chai Wan Road sits an unassuming shopping arcade. A mezzanine corridor strewn with paper lanterns, plastic flowers and a wild array of funeral offerings leads to a venerable paper crafts workshop, Hung C Lau (雄獅樓), where a large paper car leans haphazardly against a wall and paper servants stand guard at the door. Amidst this mélange, we find Anita Jack and Dan Beck of the Golden Dragon Museum in the small city of Bendigo, Australia.

Since the museum’s last visit to Hong Kong, Sun Loong made his final solo appearance at Bendigo’s 2018 Easter parade. This marks the end of an era and paves the way for Dai Gum Loong’s arrival. Anticipation for the new dragon has already begun to build. Bendigonians are anxious to see how Dai Gum Loong might manifest at next year’s parade, where he will be awakened, blessed, and lead to his new museum home in a dual procession with his predecessor.

After their January visit, Jack and her team narrowed down their short list to three dragon makers: Master Kenneth Mo, Master Hui Ka-hung and Master Ringo Leung. It came down to a head-to-head race between Hui and Leung; each was loaned a precious dragon scale and given the task of creating a silk and paper variant based on it. Each master’s scale was judged on artistic merit and workmanship. “Both were good quality and very similar to what we currently have on our dragons,” beams Jack. Both masters were flown to Bendigo and given the rare privilege of handling the city’s two imperial dragons in order to unlock their secrets.

- Master Lo On and his daughter, around 1969, with scales that he made for Sun Loong. Lo On was 39 when he made Sun Loong, the same age as Hui as he begins to create Dai Gum Loong – Photo courtesy of the Golden Dragon Museum

- Lo On shows off some of his creations – Hui Sr. sees a resemblance between his son and Lo On – Photo courtesy of the Golden Dragon Museum

In Shau Kei Wan, the groaning of trams trundling by can be heard just outside as three generations of Hui’s huddle around a folding table with Jack, Beck and their translator, Heidi Yeung, ironing out a draft contract that will seal the agreement. Dan Beck surveys the 300-square-foot workshop.

Beck, a lion dancer since the age of seven, has extensive knowledge of Chinese paper crafts and performing arts. “You can see that he’s planed the inside edges of the cane,” Beck notes, running a finger along the skeletal frame of a lion’s head. “It makes the structure stronger.” These are the kind of details that distinguish master craftsmen from amateurs.

Hui Ka-hung (許嘉雄) grew up in a world of kung fu and the associated arts of lion and dragon dancing. He began taking an interest in the lions’ heads as a child, and by dismantling, re-assembling and repairing them, the young autodidact slowly grew into a craftsman. He created his first lion at just 7 years old. At 13, he began an apprenticeship at a paper crafts shop and has stayed in the same trade ever since.

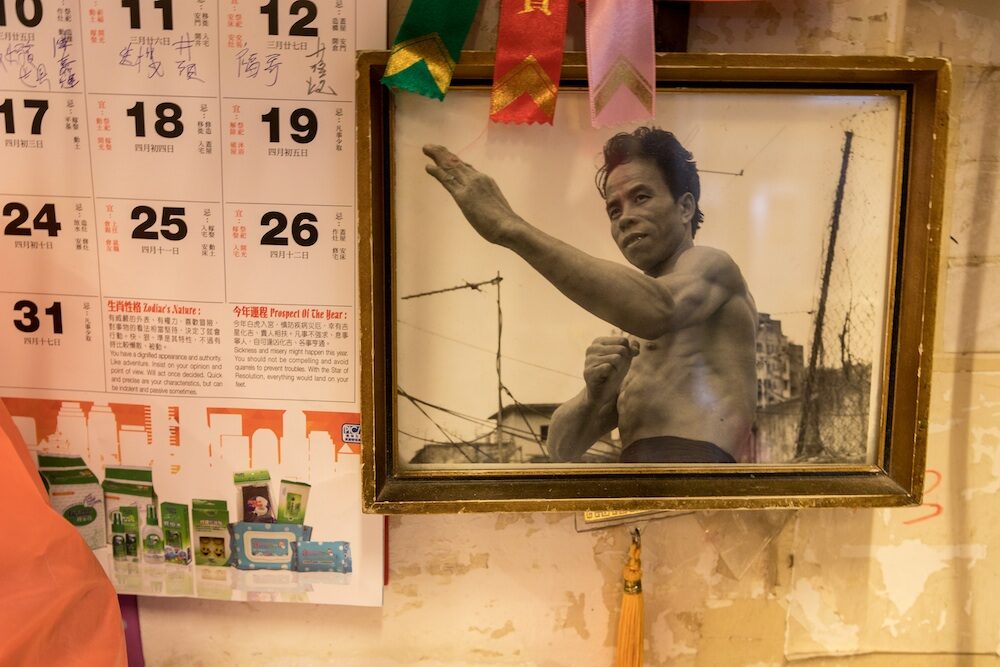

Hui’s father, Hui Cheung-jun (許祥進), sits close by. Photographs of the patriarch as a young man are scattered around the workshop. In them he ripples with lean muscle, performing leaping feats of kung fu. The retired businessman became a paper crafts sifu by learning from his son, rather than the other way round.

“People think it’s funny,” Hui laughs, “because most of the time they assume that the craft is passed down through the generations but I’ve passed it down to my father.”

Photographs of Hui’s father as a young man are scattered around the workshop. In them he ripples with lean muscle, performing leaping feats of martial arts – Photo by Billy Potts

Rounding out the team is 19-year-old Hui Siu-kei (許兆基), Hui’s nephew, who grew up in the shop. Helping out before and after school, the youngest Hui left his studies at 16 and has since devoted all his time to making lions and dragons; he is a master craftsman in his own right. “Compared with me he’s a late starter,” Hui says of his millennial protégé. Even so, Hui junior makes up to 120 lion heads a year, compared to the several dozen a year that his uncle made at the same age. Dai Gum Loong will be the young sifu’s fifth dragon.

“We are very happy doing this with three generations working side by side,” says the elder Hui. “This commission is very important to us because in this life there won’t be a second chance to do anything like this.” The elder Hui feels it is fate that has brought Dai Gum Loong to their doorstep. “Lo On sifu was 39 when he made Sun Loong and [my son] is 39 as he is about to create Dai Gum Loong. He even bears a slight resemblance to Lo On!” he exclaims.

Fate aside, the dragon makers are adamant about one thing. “I just want to say that we’re doing this dragon for the honor and prestige, not the money,” says Hui, rapping a bejeweled finger on the table to emphasize this point. To put this into perspective, Anita Jack draws this analogy: “As an artist [this] is like being asked to paint the Sistine Chapel. You only get one shot.”

The three sifus will work primarily on Dai Gum Loong’s head but there is much else to be done. Dai Gum Loong will likely surpass 120 meters in length and will be covered from head to tail in ornate handmade scales – about 7,000 scales in total. Hui’s entire family will be involved in this huge task. It took Hui one full day to make a single sample scale. He estimates conservatively that the entire family will be able to produce 10 to 20 scales per day, but he believes they will become faster with practice.

These days, Hong Kong dragons and their makers are both endangered species. On visiting the Golden Dragon Museum, Hui was saddened to see that that a foreign land had better preserved his cultural heritage than Hong Kong has. “In the museum, surrounded by all those Chinese artifacts, it felt sublime,” he says. “Hong Kong is so famous for its paper crafts but the government hasn’t done anything to preserve them. On the other hand, private citizens in Australia have amassed this huge and precious collection.”

After lagging behind by 50 years, the dragon maker feels it is high time for the commercially minded, unsentimental government and people of Hong Kong to wake up.

“If we don’t do something our precious artifacts will only exist elsewhere and we will have nothing,” he says.

Otherwise, the paper crafts of Hong Kong are facing many dangers. Not least of these is the dwindling number of craftsmen. By Hui’s count, there are now fewer than 30 sifu capable of creating lions and dragons – and even fewer do it full time. Some of them, such as the venerable Master Au-Yeung of Bo Wah Workshop (寶華), no longer practice their craft commercially.

For his part, Hui does what he can to show Hong Kong and the world the beauty of his art. Aside from collaboration with the government’s Intangible Cultural Heritage Office (ICHO), Hui is the only sifu in Hong Kong who is completely open about his working process.

“Lots of people don’t dare show their process [but] we don’t mind sharing it – we hope to be very transparent so you can see how this is done,” he says.

Hui regularly speaks and carries out demonstrations at universities and schools in order to bring the culture of paper crafts to the attention of a wider audience. On one project with the Hong Kong government, he even agreed to the installation of cameras in his workshop to prove that his work was entirely made in Hong Kong.

“I lasted longer than the camera’s batteries,” Hui laughs. “The cameraman had to come down at 2am to change them.”

He speculates that one reason for the secretive sifu may lie in the fact that they could be outsourcing their work to China. For years now, Hong Kong’s paper artisans have faced stiff competition from the mainland, which takes a different approach to this traditional craft. “In Hong Kong, it is an art but in the mainland, it’s an industry,” he says. Unskilled laborers work on parts in isolation, producing rough chimerical approximations with correspondingly low-price tags.

“They don’t talk about quality, only money. In Hong Kong we do this for the joy of creating something beautiful, not to earn a few thousand more.”

The opening up of China’s markets and the resulting price war has caused the Hong Kong paper crafts industry to collapse. “We used to be able to sell one lion head for HK$15,000, which was amazing for the time because gold was worth $2,000 per ounce. That means a lion was worth about seven or eight ounces of gold,” says Hui. After the mainland opened up, the price for a lion head dropped to HK$200.

A raucous celebration attended by dignitaries from both Hong Kong and Victoria marks the official start of work on Dai Gum Loong – Photo by Billy Potts

The contract between Hui and the Golden Dragon Museum was finally signed on May 30, 2018. Amidst the roar of drums and acrobatic displays of lion dancing, the premier of Victoria, Daniel Andrews, presided over a raucous signing ceremony. The premier and Jack reasserted their firm belief that they had found their man in Hui.

Alongside Hui, other sifu (Master Ringo Leung and Master Yu Ying-Hou), will also have their share of the limelight as they create magnificent qilins and lions to join Dai Gum Loong’s cortege. Master Leung may also have a hand in restoring Sun Loong.

Now the race is on for Hong Kong to create the greatest imperial dragon the world has ever seen. Unlike his predecessors, who only enjoyed the hermetic environs of the Golden Dragon Museum for the latter parts of their lives, Dai Gum Loong will spend his entire life in the museum, making it likely that he may live to parade for the next 100 years and beyond. Hui’s work and therefore the quality of Hong Kong’s craft will be under scrutiny for well over a century.

“You know,” Jack says to Hui, “if you make this [dragon] and it is what we expect, you’ll be the greatest dragon maker in the world. It’s that simple.” Hui is unruffled. This is to be a herculean task, but for the honor of his family and his home city, he is ready to answer the challenge.

This article was written by Billy Potts for Zolima CityMag on June 27, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Billy Potts.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.