An Interview with Katarina Saric – poet, writer, performer, activist-feminist (Montenegro)

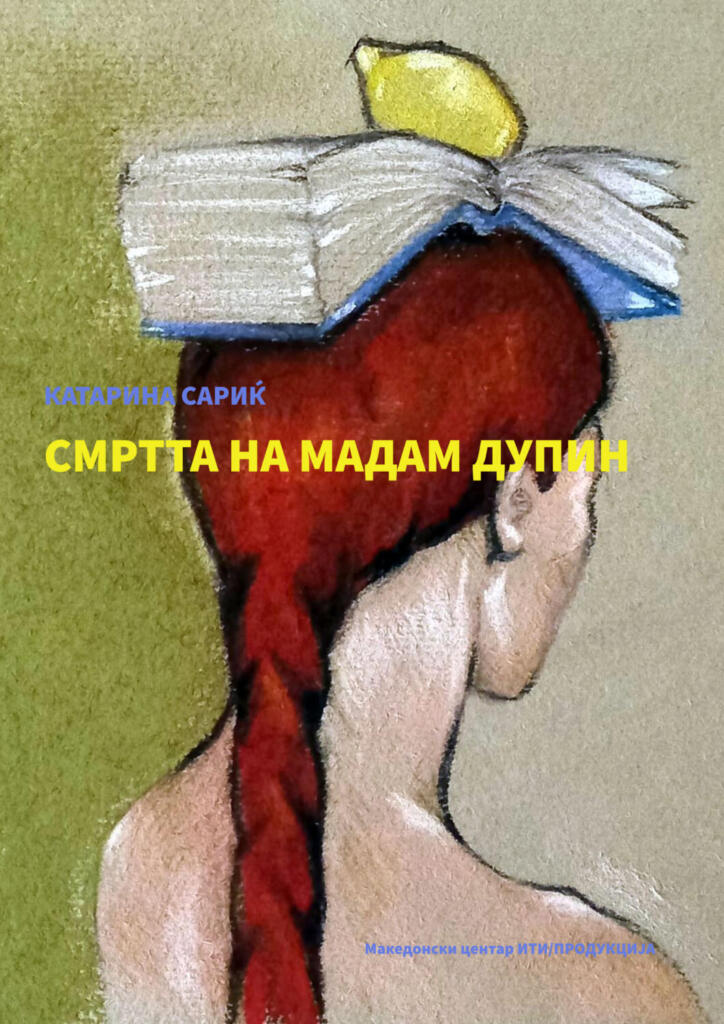

The Death of Madam Dupin

Katarina Saric (1976, Cetinje, Montenegro), is a regionally established poet, essayist, and performer. She creates engaged, feminist prose and poetry. Katarina graduated from the Faculty of Philosophy in Nikšić, in the Department of Philosophy and South Slavic Languages and Literature. She has a Master’s degree from the Faculty of Political Sciences in Podgorica, and from the Department of Social Sciences and Social Work. She is the author of several published poetic and prose works (written from 2011 to 2021), among which are Cacophony (novel); The Death of Madame Dupin (poetry); Globus Hystericus (poetry); My India, OM journey (written novel); Kamiyadai and Kamiseya (poetry); I don’t care about other social diagnoses (poetry); Acute Women’s Week (stories); Amputees (novel); Nadia, slow down, you’ll step on a bird! (novel); Caligat in Sole (philosophically fragmented trilogy); On the other side of the light (novel). Her works have been translated into ten world languages. Katarina is a freelance artist, she lives and creates between Podgorica, Montenegro, and Belgrade, Serbia.

Ivanka Apostolova Baskar: Why the title of the poetry collection The Death of Madame Dupin‘s a kind of paraphrase of the song “Smrt Popa Mila Jovovica / Death of Priest Milo Jovovich” (by text by Boja Djuranović, performed by the anthological Rambo Amadeus) – you did become famous for this intense and top-quality poetry?

Katarina Saric: The death of Madame Dupin is a certain deconstruction of the notion of the death of a bourgeois woman i.e. established conventions that force a woman to take over her spouse’s last name, and very often, with the change of status and new social role, apart of her personality also dies. As for Rambo’s poem, you noticed the similarity very minutely because it also corresponds to the murder of the cult of tradition and personality.

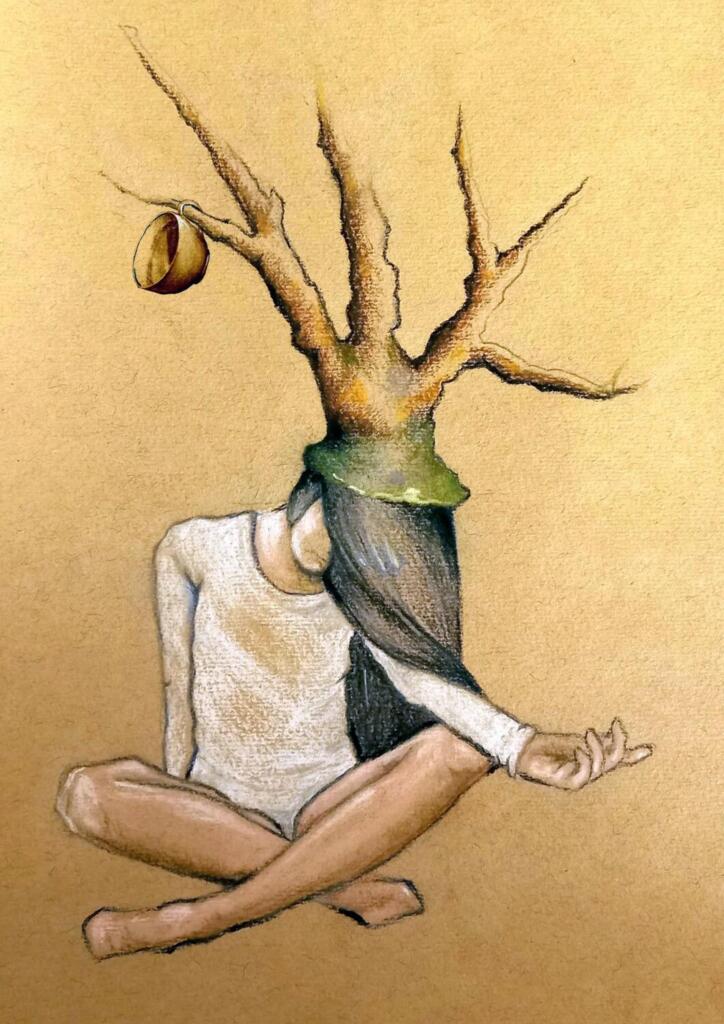

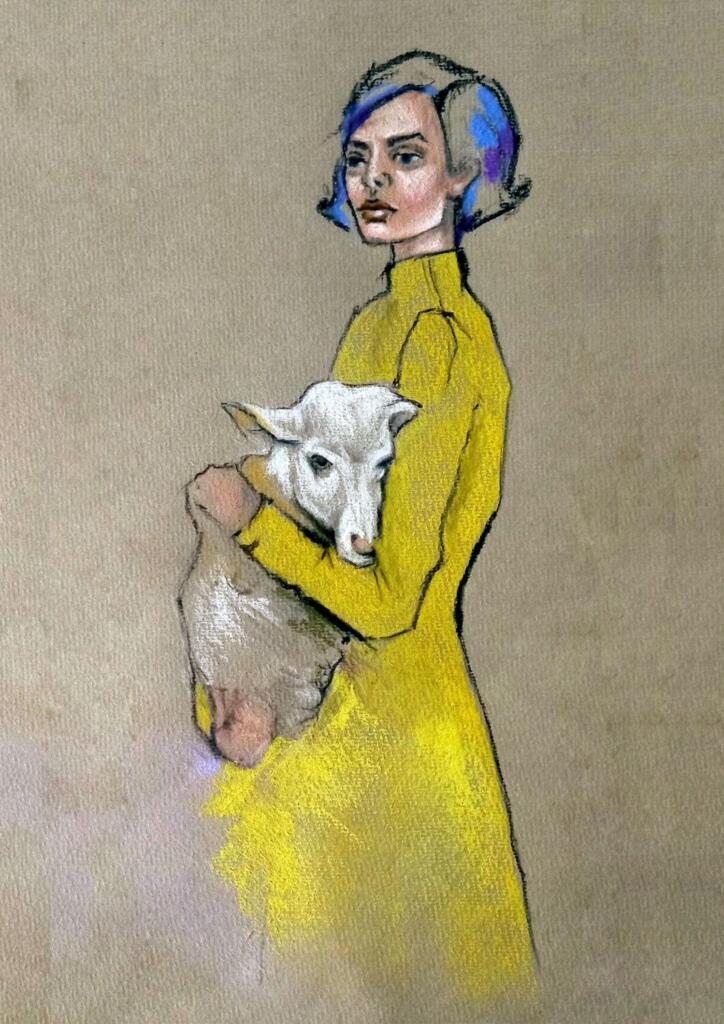

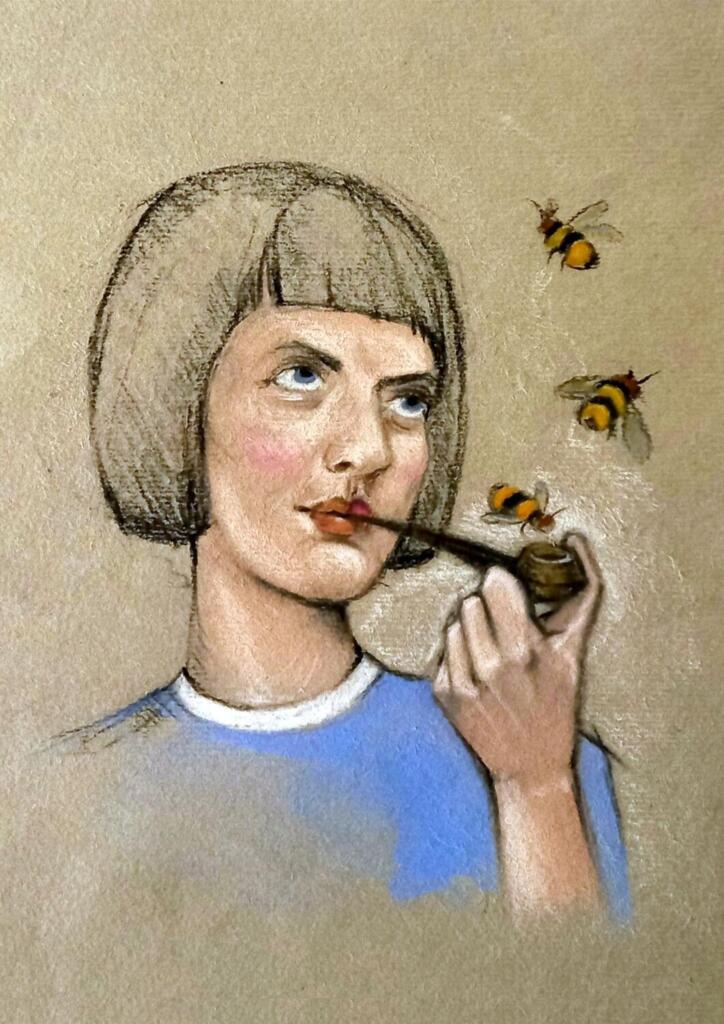

illustration by Ivana Kungulovska

IAB: By the capacity of brutal honesty, unpredictable rich eloquence, precise and deep emotionality in your poetry – you are as precise as a scalpel, knife, and arrow – you strike like a mace – you process all the positions of women in relation to Montenegrin, Balkan, European men – all kinds of men and their inevitable nature and behavior toward women in passion and love?

KS: It is safe to say that I consciously used male weapons in the fight against stereotypes and prejudice about women, primarily due to the fact that the canonical woman in world literature was described by a man. Strindberg’s Miss Juliet, Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, and Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina are just some of the unfortunate characters, stuck in bad marriages that end in madness or suicide. I wanted to find a different solution for a woman.

IAB: For me, you are the enfant/femme terrible of contemporary Montenegrin poetry? With you, there is no place for self-censorship, even at the cost of self-destruction? While modern time and space (around us), lavishly censor the art and culture of the strong individual?

KS: Thank you. I believe that the role of women in Montenegrin literature had a great influence on my literature, women in Montenegrin, either in the oral or written epic tradition, who was remembered as a woman from the shadows, the ones on whom the three pillars of the house rest, but who is not allowed to speak honestly in that same house, not to speak first when guests arrive, not to make a decision before the head of the house, a man, who has the upper hand. My literature brings out frustrations into the light of day, idols buried under the doorstep, she speaks loudly and hysterically about things from a tradition, that is kept silent about, and that without self-censorship, so as you have observed to self-destruction from which rebirth follows.

illustration by Ivana Kungulovska

IAB: From the perspective of talent, activism, and feminism, whether at home in Montenegro, does the cultural establishment accept your art? And what are their rules of the game for success and do you enter into their schemes and dilemmas, their “high-end” criteria?

KS: In Montenegro, everything changes long and slowly, my environment is strong and patriarchal, in it, men still rule in the places where decisions are made, whether they are public or intimate spaces. A woman who is strong, endowed with those qualities that are still attributed exclusively to a man’s world, A difficult fight awaits the woman in which she needs to prove that she is worthy or serious enough to enter behind the closed doors of their associations. So she is burdened with a double burden, first, for a woman to prove that she is equal to a man, and only then to realize herself through the primary personality of a woman.

IAB: In your poetry, you systematically poeticize and contextualize the world history of the pioneers of feminism George Sand, Lou Salome, Simone de Beauvoir, Marina Tsvetaeva, Alexandra Kollontai… she antichrists, seducers, provocateurs, intellectuals, monogamists, victims… all kinds of top female voices, but with an attitude of women’s right to equality? Are things changing in Montenegro as well, what is the position of women in your country – against the monotony of the sound of gusla, local chauvinism, the division of the church and the priests, the rocks and the sea, Njegosh and Europe, politics and the mafia?

KS: My poetry is, at the same time, a deconstruction of the epic code, at the heart of which is Njegosh with all the aforementioned motifs, a romantic poet and bishop around whom a national cult of personality was woven because he created it precisely at the time of the formation of the national consciousness of Montenegrins, but also the reconstruction of a new female subject. In Njegosh’s iconic song Gorski Vijenac, there is a verse in which it is said that the daughter-in-law Angelija, as disobedient, must be beaten with a whip because she dared to ask her master (husband) where he was, and he replies that he was there to sow salt and that she must believe him. I think that even in high school, the resistance to a civil marriage was deeply engraved in my consciousness and all the great heroines of her time, starting with George Sand as a pioneer who, paradoxically, fought against the institution of civil marriage and remained remembered only as Chopin’s muse, they offered resistance to traditional, established forms. The revolution is not always conducted in the open field, much more often, it is silent and is conducted daily in small fields, at the family table, in the kitchen, bathroom, and bedroom.

IAB: In the past period, your poetry has been translated into several foreign languages, was published in many relevant international poetry magazines and journals around the world, and you intensively guested at various residencies and in many regional media, what did this intense breakthrough enable you professionally?

illustration by Ivana Kungulovska

KS: Last year alone, I was translated into twenty languages, half of which are Middle or Far Eastern languages which makes me especially happy because there are many women who are still chained and trapped by tradition. The very thought that my voice reaches them, and perhaps eases their thoughts in solitude if not instills the courage to fight for change, it drives me to believe in a greater sense of my creativity beyond mere aesthetics. That socially engaged moment that is present in my literature from the very beginning, and was directed in the direction of changing the collective consciousness, directed first to cause the death of Madame Dupin and then her new birth. My Madam Dupin is scattered all over the world, they are also a Montenegrin woman with a scarf who hoeing the garden, and an Arab woman covering her face with a scarf, just like a French woman who casually wraps a scarf around her head when driving along the Riviera in a convertible car.

IAB: The Death of Madame Dupin is visual and amenable to film and theater adaptations, in the meantime you yourself give the best stage performance of your poetry- better than an actress. Tell us something about the performativity of your poetry?

KS: The performances that were born from my poetry were created quite spontaneously. When the book came out, I was invited several times to public readings in libraries that imply traditional sitting at a table, not to say seriously, at one of these readings, I started to suffocate, I literally ran out of air in a sitting position. I got up and started rampaging through the audience, oscillating in pitch, screaming or crying. Then I realized that I had to express my poetry in a different way, not that I would intentionally violate the rules of academic tradition, but to survive it. And that’s when my performance was born, which includes movement and a scene. Now I do promotions exclusively in spaces that can enable me to do so.

IAB: Is Belgrade still the key city of the ex-Yugoslav space in which the artist should test and affirm his/her/it art? So that s/he/it can then assert her/himself/itself at home and break through the world with her/his/its artifacts? And if so, then why is it still so?

KS: Belgrade, like the New York of the Balkans, is our art center where artists gather with the hope that they will succeed in building their careers. But on the other hand, that attitude is rather overestimated because Belgrade is precisely the seat of corruption, rigged contests, pre-awarded prizes, etc. I believe that it is much easier to let the work live in a small environment that is not burdened with success at all costs, and if it’s about originality and quality, it will find its way, both to readers and to critical acclaim.

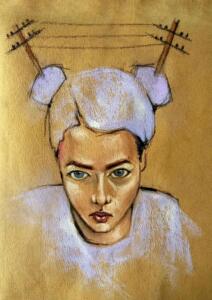

IAB: For the Macedonian translation of The Death of Madame Dupin (translator Dragana Evtimova), fine arts artist Ivana Kungulovska made 10 theater illustrations inspired by the atmosphere and content of the poetry collection. How do you experience these visual reflections, and how do they communicate with you?

KS: Visuals made by a great artist surprised me with the power that depicts my written word and changed the perspective from which I was creating. It is an extraordinary feeling to see your work come to life in a different medium than the one in which it was originally created and I am very grateful to Ivana, who infused a completely different life into the colors of Madame Dupin in her many social roles, frustrations, disappointed expectations, deaths, and rebirths. The eclectic mixture of art always contributes to the richness of presenting one and the same work, and that’s how you get his different perspectives and the bigger picture, which is very important for understanding and the interpretation of contemporary art, which today often falls into mannerism.

illustration by Ivana Kungulovska

IAB: Katerina, is this a world that is sinking into corruption, crime, Nazi-fascism, gender mishmash fictions, global instability, dark trans-humanism, men in crisis – is this kind of world afraid of energetic, talented, educated, emancipated, full-blooded women with visions, ethics, and responsibility?

KS: Fear of women did, in the first place, give birth to the world we live in today. In the same context of fear, I also place mother nature, which in most world religions is feminine. When Orestes killed Clytemnestra, Oedipus raped his mother and Agamemnon ordered Iphigenia’s sacrificed as the first-born daughter for the success of the war in Troy, when Jason stole Medea’s Golden Fleece and a man stuck the first pickaxe to explore the bowels of mother earth for ores, fear was also born of women, mothers, and daughters from the awareness of their original strength that had to be tamed. Today, we are more aware than ever, when Mother Nature strikes back at us due to the disturbed balance. The woman is her extended arm.

IAB: Is the Balkan the sub-Saharan Africa of Europe in life and poetry, in art and culture?

KS: The Balkan is exactly that, still an underexplored area that is soaked with traces of different colonization, the part of Europe that is the oldest, her knot and navel which is the scene of conflict, the gate of the West and the East, of bloody wars and silk roads, and who is still treated like a Montenegrin, Balkan woman, she must first prove to that same cradle of hers that she is worthy enough to enter behind its closed doors.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Ivanka Apostolova Baskar.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.