As the ethics of punishment are debated in mainstream media, statistics, images and unanswerable questions circulate. Post sentence detention of terrorists and the fate of Indigenous children in detention are just two of the issues Australia is currently grappling with.

When these discussions play out in a theatre, different questions are raised. The Chat, which recently completed its Melbourne season, shows the ways theatre can enrich the discourse around issues relating to the criminal justice system. It focuses on the liminal space of parole, at the edge of freedom and prison, where a prisoner’s connections to society – so brutally damaged during incarceration – can begin to repair. It also exposes participatory theatre as an unruly process, fraught with confusion and contradiction.

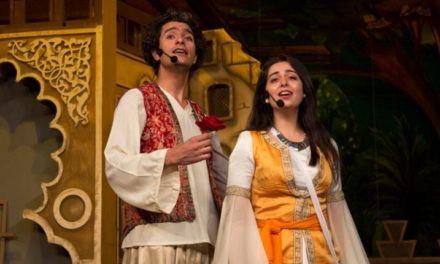

In a courageous act of co-creation, The Chat was devised by artists and former prisoners. The premise of the play is a parole interview in a future system, in 2051. Over the course of the play, the fate of a former prisoner who has breached parole is decided. Each performance features a different cast member in the “hot seat”, drawing from their own trauma of prison and experience of parole.

Their story unravels through an invented process of “transpersonalisation,” in which the roles of parole officer and former prisoner are reversed. The guiding principle of this process, audience members are assured, is “dialogue as the embodiment of love.” The improvisation of the actors in this dialogue is so practised that it does seem to embody love, even as the incredible David Woods, playing the former prisoner, drools on the table as a drug addled, father-to-be who can’t stay in rehab.

The performance I saw featured John Tjepkema, whose stunning tattoos and contagious positivity have made him something of a poster boy for the show. Before it, on the steps of Arts House, John told us that he had been clean 15 years that day and that the trauma of prison still haunts him. But The Chat isn’t just about the stories of these men and their participation in theatre. It is about us, and our participation in the justice system.

Arthur Bolkas and David Woods in The Chat, in which the fate of a prisoner who has breached parole is decided.

At one end of the stage, raised on a platform and obscured by a screen, three men chatter in a style only possible in a desk job where not all of one’s self is present. These three symbolise authority, laying bare the banalities of office life as they discuss toasties, muffins and sushi rolls amid their critique of Foucault and evaluations of each others’ performances.

In a disturbing fat suit that literally adds weight to his character, the actor and director JR Brennan is pulling the strings here, defending the experiment of transpersonalisation. These three employees are working on our behalf, to conceive, test, and implement a better justice system. And it is no accident that they appear at some moments as vile, power hungry operators, at others as well-meaning, pathetic bureaucrats. Their eccentric commitment compels us to consider our role in this system, and to focus on the differences between those who invent it and those who are bound by it.

Meanwhile the prisoners awkwardly throw their bodies around the stage; dance, destroy their criminal records in a shredder, and reenact their crimes in a kind of trauma treatment. Guided by an earnest Ashley Dyer, armed with white pearls, a soothing voice and a clipboard, they stumble through the step-by-step process of transpersonalisation under the watchful eyes of their two-tiered audience.

Towards the end of the show, audience members are chosen to join the parole board. I sit with strangers, watched by other strangers, and discuss the merits of the performance we have just seen. This scene exposes all the complexities of participation, as consensus unravels onstage. There is no question that John deserves another chance, but when the conditions on his parole emerge from the group, it becomes clear that there is also no “appropriate” response or “correct answer”.

Warm baths and incense; spending time outdoors; a group of women to support him; cooking classes; urine tests – all are suggested by the audience as ways to help John on parole. In their keenness to be kind, people seem to almost forget that John is in the room, that he might not like incense. Those without expertise are making the decisions here about crime and punishment, and about theatre. This is messy and uncomfortable, but it is truly worthwhile.

Because as much as we all want a reliable, fair and consistent justice system, there is nothing easy about judging each other.

![]()

Alexandra Crosby, Lecturer, Interdisciplinary Design Studies, University of Technology Sydney

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Alexandra Crosby.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.