Solomon Mikhoels, one of the founders and greatest stars of the Soviet Yiddish theater, wrote in 1919, “fierce raged the tempest of revolution on the street…and human eyes and overly human thoughts flounced in fear and confusion among the chaos of destruction and haste of new construction…and at this very time, when entire worlds were cracking, dying and being replaced with new worlds, it happened; it may seem something very small [to others], but for us, Jews, it was a great miracle—Jewish theater was born.”

Of the Jewish cultural startups that proliferated in revolutionary Russia, the modest Yiddish Theatrical Studio, held the mythical status of “the first state Jewish theater in the thousand-year history of the people,” as Mikhoels put it. It was founded in January 1919 in Petrograd and would eventually become the State Yiddish Theater, also known by Russian acronym “GOSET.” Mikhoels, then Shlomo Vovsi, a law student at Petrograd University, was a co-founder and one of the Studio’s first students. Its principal founder and teacher was a young director named Aleksei Granovskii, a student of Max Reinhardt, the standard-bearer of modern German and European theater. In January and July 1919, the Studio presented its first works to the public: six one-act plays by Maurice Maeterlinck, Sholem Asch, Granovskii and Vovsi, and the four-act play Uriel Akosta by Karl Gutzkov. The Studio’s manifesto proclaimed the perpetual search for stage innovation to be among its chief objectives.

In 1920, in search of new forms of artistic expression and means of support, Granovskii’s Yiddish Studio moved to Moscow. There it gained a permanent home and became the State Yiddish Theater or GOSET. The theater opened in January 1921 with An Evening of Sholem Aleichem, based on the short stories of the classic Yiddish author. It was directed by Granovskii and designed by the young Marc Chagall. Granovskii also commissioned Chagall to paint the foyer. Thus, Chagall’s Introduction to Jewish Theater, a visual interpretation of Yiddish avant-garde theater, came into being. In Moscow, government-sponsored culture ideologues explained to Granovskii that “a Jew on stage should not be an everyday Jew, but an absolute universal Jew.” Granovskii and his troupe therefore sought to develop the theatrical and artistic aspects of the Jewish character in order to achieve a universal representation of Jewish life on stage. It was then that Shlomo Vovsi, GOSET’s star actor, took the stage name Solomon Mikhoels, and avant-garde Yiddish theater truly came into being.

Marc Chagall “Introduction to the Jewish Theatre,” 1920

The Moscow State Yiddish Theater (MSYT) collection at the Blavatnik Archive Foundation (BAF) is a rich and important resource on the history of the GOSET and Soviet Yiddish culture in general. The collection contains a wealth of material including photographs, drawings and hundreds of documents and books in Russian, Yiddish, Ukrainian, Hebrew, German, and French. They are from the 1900s to the 1970s, with most from GOSET’s golden years in the 1920s-1930s. In scope and significance, the MSYT collection at BAF complements other archival collections of GOSET materials. There are two in Russia (at the Russian State Archives for Literature and Art and the A.A. Bakhrushin State Theatrical Museum in Moscow), and one in Israel (at the Israel Goor Theatre Archives and Museum at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem). Unlike the other collections, the MSYT collection at BAF is fully digitized, cataloged, and accessible online.

GOSET troupe, Moscow, 1929 (MSYT_00564, BAF)

The MSYT collection was formerly the family archive of Iustina Minkova and Solomon (Zalmen) Zil’berblat, Yiddish actors and members of the GOSET troupe. Both Minkova and Zil’berblat were among the first cohort of Soviet Yiddish actors who started their careers in 1919 as students at the Petrograd Yiddish Theatrical Studio, led by Granovskii. Minkova was one of GOSET’s leading actors, playing major roles in the theater’s most successful productions such as Eti Meni in Sholem Aleichem’s 200,000 and Goneril in William Shakespeare’s King Lear. In 1935, she was awarded the prestigious title of Honorary Actor by the Soviet government. Minkova’s husband, Zil’berblat, played mostly supporting roles. His only major role was that of Hershele, the main character in Moisei Gershenzon’s Hershele Ostropoler. Zil’berblat was also active in the actor’s union, performed some administrative tasks in the theater, and organized extracurricular events such as celebrations of important events related to the theater’s history and Yiddish culture. He was also an avid collector of books and documents on GOSET’s history and Yiddish theater in general.

In the 1920s, Minkova, Zil’berblat, Mikhoels, and other members of the troupe led by Granovskii were able to transform the modest Yiddish studio into the famous GOSET, one of the best avant-garde theaters competing with major Moscow troupes. In the 1900s-1920s, Moscow was the epicenter of a worldwide theatrical revolution, where daring productions, innovative drama, and cutting-edge stage designs were created. Directors such as Konstantin Stanislavski, stage designers such as Leon Bakst, and theatrical troupes such as the Moscow Art Theater (MKhAT) led the revolution. In the 1920s, they were joined by a host of talented directors, actors, and theater troupes, including two Jewish theaters: the Hebrew Habima led by Nahum Zemach, and the Yiddish GOSET.

These troupes differed not only in style and repertoire, but also in the way they were run. The famous Soviet actor Igor’ Il’inskii remembered his work at the MKhAT II thus: “Our rehearsals took place in a remarkable atmosphere. Everything, including directing and acting, was done collectively. During my entire career, I’ve never seen such an engaging, friendly, and creative atmosphere…where every individual artist could do whatever he wanted.” But in 1924, when the world-famous director and actor Mikhail Chekhov assumed leadership of the MKhAT II, he insisted that the troupe follow his own vision. Another Russian theatrical revolutionary, Vsevolod Meyerhold, ran the Moscow Theater of the Revolution like a dictator, “overshadowing the actors, [who were] seen as mere instruments for the realization of his interesting ideas,” as his teacher Stanislavski put it.

In spite of their differences, these theater troupes shared artistic principles and creative goals that were in sync with the revolutionary era. Directors and actors often changed troupes following a change in priorities, searching for the best opportunities to realize their creative potential. The young but accomplished director Evgenii Vakhtangov, whose career was launched at MKhAT, went on to work with Habima then founded his own studio. At the MKhAT II, Delo (The Affair) by Aleksandr Sukhovo-Kobylin and other realistic productions directed by Boris Sushkevich shared the stage with symbolist and expressionist performances by other directors.

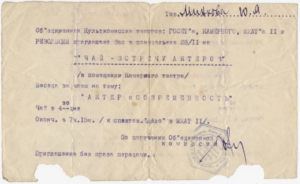

Invitation to the “Actors’ meeting and tea” at the Moscow Kamernyi (Chamber) theater, 1927 (MSYT_00213, BAF)

Directors and actors from different Moscow theaters frequently met informally to discuss theatrical and non-theatrical matters. In November 1927, Minkova was invited to one such meeting. It was a collective discussion on “the actor and modernity,” followed by a tea party at the Moscow Kamernyi (Chamber) Theater. Tea was served at 4:30 pm, and at 7:15 pm the participants were expected to attend the evening performance of Delo (The Affair). The invitation was from the Actors’ Union Cultural Commission of Theaters, including GOSET, Kamernyi Theater, MKhAT II, and the Theater of the Revolution. This shows that in the 1920s, GOSET was part of the Moscow theatrical elite, occupying a prestigious spot among the select few leading theaters.

Iustina Minkova (third from the right) at the “Actors’ meeting and tea” at the Moscow Kamernyi (Chamber) theater, Moscow, 1927 (MSYT_00071, BAF)

In the 1920s, some of these theater troupes represented Soviet revolutionary art abroad. In 1928, Habima and GOSET embarked on tours to Europe, followed by Meyerhold’s troupe in 1930. Aleksandr Tairov’s Kamernyi Theater toured Europe in 1923, 1925, and 1930 with such success that German critics declared it a “symbol of the new Russian art.” Meanwhile, at home in the USSR, the emerging party state was tightening its control over art, and theater in particular. Fearing for their creative freedom and safety, some actors, directors, and entire theater troupes, such as Mikhail Chekhov, Aleksei Granovskii, and Habima, never returned to the USSR.

Those who did return soon found themselves out of sync with the new style of Socialist realism. They were faulted by Soviet critics for the “formalism” of their art, for being insensitive to the “real interests of the toiling masses,” and for not contributing to the building of socialism. As a result, MKhAT II was shut down by the authorities in 1936. In 1949, both GOSET and the Kamernyi Theater were liquidated. Vsevolod Meyerhold was executed in 1940 and Solomon Mikhoels, the head of GOSET since 1929, was assassinated in 1948.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Vassili Schedrin.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.