Choreographer and dancer Daniel Linehan places dancers in a hyper-structured environment. In this way, his performances investigate how society conditions us and puts our bodies and psyches under pressure. His most recent work, Flood, takes a step beyond the establishment of this condition and for the first time short-circuits this structure.

Kristof: Several of your works involve a combination of restriction of the dancers’ movements by a choreographic system and playfulness or humor. In Flood, this creates an interesting tension as well, as the dancers repeat a movement sequence, with each repetition announced by timer-like beeps, each time becoming shorter and shorter, forcing the dancers to select from the material and move faster and faster, which then again becomes “fun.”

Daniel: “It’s true that in each of my pieces I often start from a certain restriction or limitation. This also relates to the title of the book I made in 2012, A No Can Make Space: the idea of creating a perimeter or framework that I’m working inside of. It actually enables me to know what to do and in a way to find the freedom within that frame or to discover what are the boundaries and where can I push them. For each piece, I develop a system of rules and sometimes challenge those rules, but nevertheless, start from this system. The same goes for the concepts or ideas I work with: I always try to be rigorous with them; in that sense, they are also some kind of restriction. I think that the playfulness resembles how in games and sports there are also rules and restrictions, but the point is to play inside of these. So that’s kind of how I treat choreography as well. Not always, but often creating different situations that are game-like where the dancers have a number of rules, leaving an area of uncertainty as well.”

“I was influenced, although I only read it a couple of years ago, by the Dutch culture historian Johan Huizinga’s book Homo Ludens. When I read it, I realized that it related to the work I was doing. The way he describes a man as a playing animal was really interesting. For him, a play is not necessarily about frivolousness but it is often taken quite seriously. Huizinga describes different aspects of human culture as all deriving from play, like the judicial system or war. The play is something separated from the normal everyday life where a different set of rules apply. Also, the arts and performance are kind of like a separate sphere.”

This connection between play and law feels rather unexpected. You could also say that when it becomes law, play starts to have an impact on the world outside of this separate sphere and becomes a matter of power. Other thinkers consider play to be the opposite play of structure, breaking instead of developing them. During your performances, is there still a game-quality going on? Is it all scored, or is there still a game being played?

“When it comes to this, I think my work has evolved over time. I somehow become more open to game-like structures during the performance itself. For instance, in Gaze is Gap is a Ghost (2012) in which the dancers have to relate to video images and The Karaoke Dialogues (2014) where projected text forms the structuring element, I encouraged the dancers to be very playful inside of it, but the piece and its timing are very set. Whereas in dbddbb (2015) and Flood there is also set material but there are also moments, sequences of the performance where the dancers have to make choices inside the piece. For instance, in Flood, they start out with a rigid choreography – although some of it is open in terms of the exact form – but as it goes into the repetitive cycles and the time reduces, they each night find their own way of how to reduce that material and they then have to stick to it throughout the performance. In dbddbb, there are also moments in which we all know the same text but it is not set who is going to say which line next so we have to listen to each other very carefully. There is something set, but the group has to figure out how to make that set thing work without it being written beforehand who does what.”

“It is not necessarily legible to the audience to see what is the game and what it set and maybe this is something I want to work on. But for the moment I use it more like a performative state. The dancers are in a state of alertness because they have to make decisions in the moment. I’m not sure if the audience can read which aspects are improvised or which aspects are being played.”

Perhaps as a spectator, you don’t see how the game works internally, but in Flood, there are some “rules” being communicated, such as the beeps indicating time structure. In the Karaoke Dialogues the screens that generate pressure on the dancers’ movements. In that sense, you can also discern a kind of “machine,” a structure in which the dancers move.

“That’s true. In Not About Everything, a solo from 2007 in which I continuously spin around, there is the audio recording of the text I have to stay in time which, just like the texts on the screen in the Karaoke Dialogues, or the video recordings in Gaze is a Gap is a Ghost. In these works where everything is kind of written, you can see the game of having to recreate the writing and you see where the dancers fail or where we purposefully make a décalage between the performance and the recording.”

You now describe this game as an internally structuring principle, but there are small references to the “external” world in your pieces. Is there a connection with the rules and restrictions in the world outside of the performance? Flood, for instance, is a very timely notion already. But also in Not About Everything and The Karaoke Dialogues you refer to ISIS or “offshore detention camps.”

“It’s easy for me to become very formal, not only in terms of dance, but also when I work with other media, relating text or video to dance. That’s an inclination I have, but I also want the work to be able to connect to something outside of the stage space. So when I mention current events or issues in the news in Not About Everything, it is an opportunity to suddenly be outside of the here and now and to connect to something that’s not only self-referential. In the Karaoke Dialogues I was working with classical texts, some from centuries ago, but I wanted to find ways to make ideas from the texts relevant for today. For example, in the original text from Cervantes, a woman crosses a bridge from one place to another, and she must state where she is going and for what purpose. In today’s context, this still has relevance. It might not be a matter of crossing a bridge, but crossing borders between nations has the potential to become a very absurd situation, in which the authorities do not trust the purpose of the migrants or refugees, and they become permanently stuck in a state of being in-between, unable to go on with their lives and unable to go back.

Language is then not only a means of structuring, a medium the dancers have to relate to, but also a way to connect the choreography to external references?

“Moreover, in dbddbb and Flood, when we weren’t using real text, a dancer vocalizing already creates a meaning. When you add voice to a movement, even in a non-verbal way, you can make it seem more like martial arts or a robot. Vocalizing creates meaning, whether or not it is text. There are little sounds in dbddbb, like the “cling” of metals touching and these then bring materiality in the scenario, even if only for a moment. Similarly, there are mini-situations of a group moving together and vocalizing together and even if you don’t know what they are saying, it resembles a certain situation, like a protest or a folkloric dance.”

In the program leaflet of dbddbb, you said that we might need a new language in order to go to a new phase. After seeing Flood, where you could indeed interpret the sounds and movements of the dancers as those of robots, I wonder whether there is something futuristic of science-fiction-like about your work?

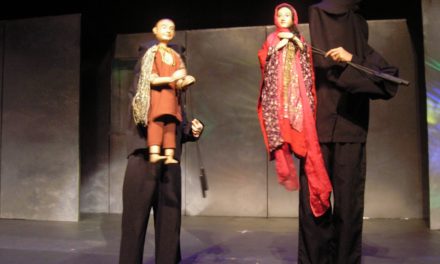

“We wanted to keep this ambiguous and reflect on a larger time frame, not limited to the future. In dbddbb, there is the idea that we are a small tribe or band of people that might come from a distant past, another planet, or a post-catastrophic future after the destruction of all technology. Also in Flood, when we created the vocal sounds, we imagined what humans creating sounds would be like 10,000 years ago or 10,000 years in the future. In the scenography and the costumes this ambiguity returns, as we all work on the same concepts. For example in the costumes of Flood (designed by Frédéric Denis) there are wires coming out, referring perhaps to something more technological, but also this folkloric fabric is being used. The colorful lines of makeup on the dancers’ faces in dbddbb remind of ancient ritual markings and have a futuristic feel as well.”

“I wanted to activate the imagination of the audience in diverse ways, so that at one moment it seems like the performers are speaking to them from the future, and at another moment it seems like the performers are speaking to them from the past. The dancers’ movements and sounds are bizarre and not of the contemporary world, but at the same time there is something familiar about them—one moment in dbddbb looks and sounds like a protest march, another moment looks and sounds like a dance party. I wanted the audience to see the events as not of this time, yet still connected to this time. I’m interested in the thought that we don’t live in a particularly special time in history, but that there are common human experiences that transcend particular historical moments.”

In Flood there is perhaps a real sense of after-time or post-history when after the increasingly intense repetitions of the movement sequence, a black-out initiates a next part in which the dancers move between curtains hanging center stage and become shadows, walking in a calm pace. But perhaps this moment of “release” is a recurrent element in your work, as Not About Everything has this too.

“I often end my pieces with a quiet reflection, because it is true that they tend to be very busy, or dense, or full. With Not About Everything, I wanted this quiet moment as a moment of reflection, rather than finishing spinning and then bowing, as that would almost too much emphasize the virtuosity. People sometimes have questions about the ending, as they see this as a conceptual break from what seemed to be a whole. In Flood* this section is longer. With this performance, I wanted to work with the idea of appearance and disappearance and also an idea of acceleration and through that acceleration a process of loss. When the dancers re-emerge in a different physical state, we spoke about it as an archeology of what came before, as if a long time had passed. Normally archeology digs through objects, but now we come back to some of the dance movements in a fragmented way. We try to re-find them or reconnect them in different ways.”

“One way of looking at this transition from dense activity to a more contemplative mode, and the moment of disappearance that separates them in Flood, as an ecologically catastrophic event that we are probably already in the midst of. As our lifestyles and our technologies accelerate, we in the meantime ignore the mass extinction that is being caused by this flood of human activity. It has the potential to reach a crisis point where there is a disappearance of human civilization as we have known it. The moment when the dancers re-emerge and conduct their ‘archaeology’ of the past could be seen as a moment a thousand years in the future, trying to make sense of the traces and fragments of our current civilization.”

You already mentioned you combine different media and some of these, such as video or sound recording are “technological.” How do you consider technology as a choreographic element?

“So far, I have been trying to use technology not necessarily in terms of special effects, but more in very simple ways, because in daily life I – we all – also relate to technology all the time. In Zombie Aporia (2011), I strapped an iPod to my head and this iPod was then recording – not a high tech setup at all, I looked rather ridiculous. The audience could see what I was seeing and sometimes the video material, in turn, became a score to move. So I use technology more in a daily or amateurish way to think about how the body nowadays relates to technology. I don’t often see in dance a body encountering technology in such a way and this interests me.”

“Even in the latest pieces, in which I don’t explicitly work with technology, people have commented on a kind of quality of the movement in my work that they perceive as being ‘technological.’ Perhaps this quality is derived from its source of inspiration. In Flood we were working with the movement of vectors: a resistance-less movement from one place to another and that’s also the way technology works nowadays where the internet connects us almost instantaneously. In Zombie Aporia, we were following video images and this created a different quality of movement than when it would have been generated otherwise.”

“The way we deal with technology nowadays is a lot about multitasking and this returns in my work as well. Also in Zombie Aporia, we had to watch the video at the same time as we were singing a song that had nothing to do with it, and these two things have a different rhythm from each other. In some sense it was a way to find out, to push the body, to see what it would be capable of otherwise. Technology then became a tool for the body to produce two rhythms at once: one vocally, one physically. By just giving the body over to automatically imitating what it sees on the video, while we say a memorized text, we somehow managed to use two different halves of the brain. Technology here enabled us to do this. On the other hand, in this moment of the piece when the dancers imitate the video, they could also be seen as unconscious zombies, fixated on the screen and unable to tear their attention away from it. I think many people can relate to this feeling of being seduced and trapped by screens. In the performance, it is a challenge that overwhelms the brain in that moment. This generates a specific way of performing. When the brain is full and busy, you don’t have space to think ‘how should I perform this,’ ‘what is my state,’ you just are in that state. Especially in past performances, I liked to have performative tasks that just fill up the brain so you just have to execute the task. You avoid becoming self-conscious about how you are doing it. It is difficult to say, but there is something about the density of my work that must be typically American. I really enjoy work that is spare, and spacious, but I never end up making work that is like that.”

This article was originally published on E-tcetera. Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kristof van Baarle.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.