Today’s obvious was most likely yesterday’s incredible. This is the conceit at the heart of Dr Semmelweis, a new play written by Stephen Brown with Mark Rylance, which has transferred to London’s Harold Pinter Theatre following a sold-out run at the Bristol Old Vic in early 2022. Based on the biography of its titular figure, this gripping medical drama has a lyrical, tender heart that amplifies its historical tale of a man willing to burn all his bridges in his devotion to science.

Led by Rylance’s towering performance as the Hungarian physician Ignaz Semmelweis, an early pioneer of antiseptic procedures, Tom Morris’s stately production plunges us into a world where scientific truths and long-held beliefs collide with shattering results. Dr Semmelweis opens twelve years after its central events, when Semmelweis has been living in Hungary with his pregnant wife Maria. An unannounced visit from his former colleagues, who implore him to present his theory of “decaying organic matter” at an upcoming conference, triggers an extended series of flashbacks into his days as a junior doctor at the Vienna General Hospital’s obstetrical clinic. It was during this period in the late 1840s that a younger Semmelweis was intrigued by the disparity in the postpartum mortality rates between the doctors’ and midwives’ wards.

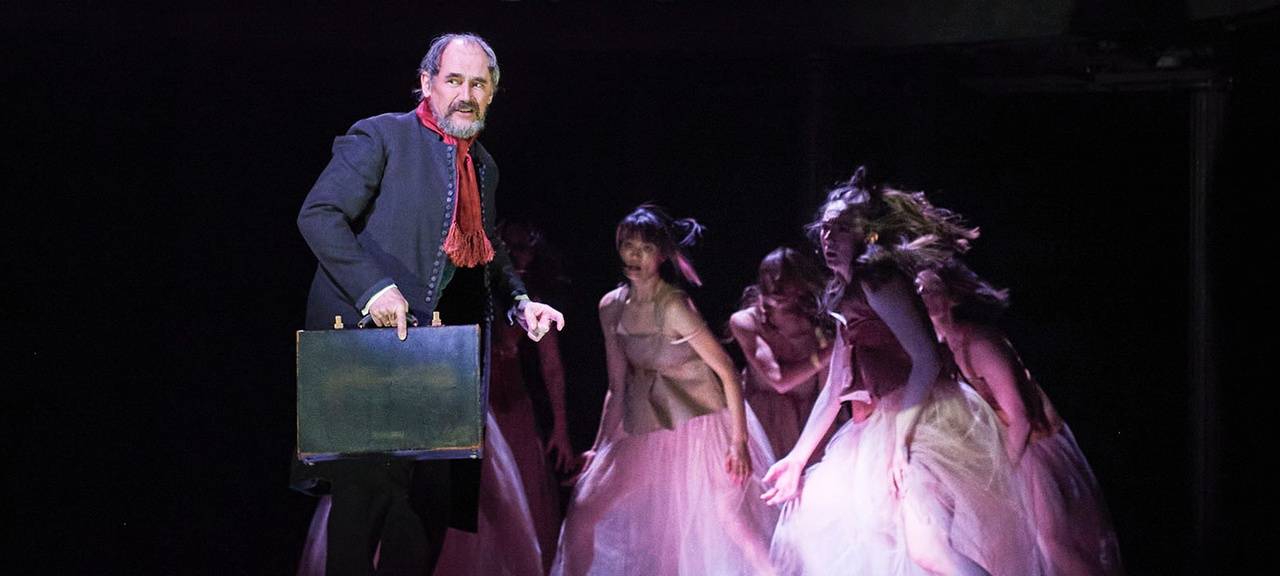

As Semmelweis walks us through his discovery of the life-saving importance of hand disinfection, he reveals the extent to which he is still haunted and hounded by it. Even the telling of the story requires him to commune with the dead: throughout, both Semmelweis’s reconstruction of past events and Maria’s direct address to the audience are permeated by an ensemble of ghostly Mothers, whose balletic movement (choreographed by Antonia Franceschi) provides an expressionistic tenor to the proceedings. These are the spirits of the women Semmelweis failed to save and feels obliged to carry with him. They crowd upon him, fling themselves to the ground, pursue one another in fits of despair.

How Semmelweis goes about shedding light on the cause of “childbed fever” is truly remarkable: he not only also digs into the archival records and analyses the historical numbers, but also conducts a natural experiment by switching the two wards for a time. The thrill of impending discovery is given visual and musical rhythm on stage, as his collaborators Dr Franz Arneth (Ewan Black), Dr Ferdinand von Hebra (Felix Hayes), and Nurse Müller (Pauline McLynn) join Semmelweis in his feverish pursuit of scientific truth. The play’s foregrounding of Müller as an unlikely but essential collaborator, doomed to a tragic end, gains further strength from McLynn’s clear-eyed, grounded performance. Performed lucidly by Amanda Wilkin, Semmelweis’s wife Maria is the constant spectator to his flashbacks, watching the scenes in varying degrees of puzzlement and dismay.

Ti Green’s two-storey set, featuring a revolve and an imposing oculus through which shafts of light pass, variously evokes both the inside of Semmelweis’s mind and the interior of a mid-nineteenth-century hospital. A string ensemble, meanwhile, elegantly underscores the action with music composed by Adrian Sutton: the jarring notes effectively convey Semmelweis’s inner torments over the years. Richard Howell’s lush, often-warm lighting paints Caravaggesque tableaux of psychological intensity and atmospheric hold. Imbued with these elements, the stage gradually turns into a chamber of horrors reflective of Semmelweis’s evolving turmoil.

Along the way, we witness Semmelweis encounter several forms of institutional and bureaucratic resistance, most importantly by the hospital’s senior doctor Johann Klein (Alan Williams). Because the medical community takes offense at Semmelweis’s suggestion that doctors are unwittingly killing their patients by failing to disinfect their hands, they demonize him and disavow his findings. And this comes with a heavy cost: during Semmelweis’s professional exile from Vienna over those twelve years, we find out, almost one thousand postpartum deaths occurred, all of which could have been avoided easily.

Crucially, though, the medical establishment is not the only vituperator in this play: Semmelweis himself increasingly strikes us as an irreverent and irascible figure whose profound attachment to his theory leads him to dismiss anyone standing in his way. Hard as stone, he alienates even his closest supporters in the name of defending his truth. The play’s slightly cumbersome second act portrays the older Semmelweis as an unhinged figure on the verge of insanity. Dr Semmelweis makes a clear effort to counterbalance Semmelweis’s scientific integrity with his darker side as a proud and obstinate man.

Mark Rylance’s performance masterfully captures the inherent complexity of this difficult but ingenious figure: for all his dogged shouting and harsh dismissiveness, it is difficult not to be charmed by his almost child-like dedication to a truth that could save innumerable lives. Rylance embraces the character’s ambivalence with bravura. In this, he is supported by the various achievements of Tom Morris’s staging, which pulls off the arduous task of presenting a scientific drama of ideas with expressionistic flair and choreographic buttressing. The busy traffic on stage rarely feels unwarranted: instead, our movements from crowded scenes of multifarious action to solo moments of reflective stillness are both smooth and illuminating.

This compelling dramatization of Semmelweis’s literal and figurative straightjacketing is multiply resonant for today’s audience. In a world reeling not only from a pandemic, but ever-changing forms of prejudice and precarity, Dr Semmelweis offers a memorable object lesson on the practical complexities of scientific progress and the deathly perils of bureaucratic conservatism. It’s a lesson surely worth engaging with — and learning from.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Mert Dilek.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.