Dorothy Parker’s take on suicide is called “Resumé”: it goes, “Razors pain you; Rivers are damp; Acids stain you; And drugs cause cramp. Guns aren’t lawful; Nooses give; Gas smells awful; You might as well live.” Although this seems to cover the terrain, Alice Birch’s powerful new play, Anatomy of a Suicide at The Royal Court Theatre, adds a couple more methods of doing away with yourself, as well as an implicit argument for avoiding the necessity of suicide. And although this drama takes up some 237 pages of published text, director Katie Mitchell proves you can stage it in 120 minutes without a break.

And what an excruciating, yet devastatingly brilliant, two hours they are. The play shows episodes from the life of the women of one family spread over three time periods: one starts in the 1970s, the next in the 1990s and the third in the 2030s. In the opening scene, set in a hospital corridor, Carol tries to explain to her husband John why she tried to kill herself by slitting her wrists. Later, their daughter Anna finds herself in a similar situation to that of her depressed mother, while, in turn, her mixed-race daughter Bonnie also begins the play in a hospital — although, in an example of the piece’s wry humour, she is a nurse rather than a patient. But she has problems of her own.

All three storylines take place simultaneously on stage, which is divided into three spaces. The resulting complex stage picture means that Birch and Mitchell can intensify the experiences of each of the women — Carol, Anna and Bonnie — by showing how they are echoed in the feelings of their bloodline. What comes across most strongly, especially when the women echo each other’s words, is the sense that each of them is a part of a web, a skein of emotions, that invisibly link their life stories. The play presents powerful images of extremes of feeling, amplified by the simultaneity of time, all of them taking place as the normal stream of daily life flows on.

So people meet, they fall in love, they have children. Everything revolves around Carol and John’s house, which Anna — who marries Jamie — inherits. It is this house, so full of memories and marks — a stained floor, a discoloured ceiling, a place full of recollected feeling — that Carol’s granddaughter Bonnie attempts to sell later in the story. At the same time, she is haunted by memories and by the thought that suicide not only runs in the family, but also that misery seems to cling to the fabric of a location, a kind of ghost which leaves its indelible and almost ineffable fingerprints on every wall, banister and door handle. The house is soaked in depression.

In every scene, Birch suggests that happiness is fragile. The question “Are you happy?” recurs constantly throughout the play, with the women articulating, or failing to express, their anger and disappointment at the poverty of life’s rewards. They feel ambivalence about motherhood, and try to assert their independence. When their names are used by men as an instrument of control, the women try in vain to slip free. What’s most shocking is the continued brutality of medical interventions aimed at curing Carol and Anna of depression: the treatment is electroconvulsive therapy. To enhance the story, Birch paints sketchy subjective images of drowning, of burial, of suffocation. The feeling is that these women find living unbearable; they can scarcely breathe.

But although Birch vividly conveys the hyper-sensitivity of her characters, especially her women, and implies that we all find it difficult to understand exactly how others see us, this is not a flawless work. The Pinteresque repetition of some stretches of dialogue feels a bit wearisome, the lack of any explanation for mental distress is frustrating, and the thinness of the plotting can be annoying. The content of many of the conversations lacks ideas that are anything like as compelling as the experiences shown. Some anatomy! Also, the difficulty of writing in the triptych theatre form has sucked mush of the energy out of these exchanges: form triumphs over content. Moreover, there is something despairing in the suggestion that depression can only be cured by self-harm, that it is hereditary, and setting one strand in the future is pointless unless it illuminates the present. Sadly, Birch and Mitchell are better at representing darkness than at throwing light on their subject.

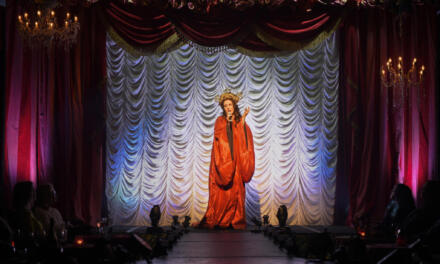

But the aesthetics of Mitchell’s production are outstanding. To call the bare brutalism of Alex Eales’s set, enhanced by James Farncombe’s lighting and Paul Clark’s music, atmospheric is an understatement: it’s a throat-grabbing, freezing world. Each of the women appears in different colours — shades of red for Carol, green and blue for Anna, and white and grey for Bonnie — and costume changes are performed in full view, adding to the feeling of these women’s vulnerability. And Mitchell’s ensemble cast — Hattie Morahan (Carol), Kate O’Flynn (Anna), Adelle Leonce (Bonnie), Paul Hilton (John) and Gershwyn Eustache Jnr (Jamie) — are always convincing, acting with absolute integrity and delivering the syncopated music of Birch’s text faultlessly. Five other actors play the bit parts. The result is an exceptionally strong staging of an innovative piece of new writing.

This article was also published on AleksSierz.co.uk. Reposted with permission. Read the original article here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.