Laurence Senelick, Fletcher Professor of Drama and Oratory Emeritus, is a theatre historian extraordinaire. He has written numerous books and countless articles on topics ranging from queer culture to the history of directing to Russian and Soviet theatre to theatre and the visual arts, translation, multicultural theatre, and more. After 45 years of teaching at Tufts University, having mentored hundreds of students, Professor Senelick retired earlier this year.

Irina Yakubovskaya: Congratulations on your retirement. How does it feel?

Laurence Senelick: I like the idea of having all my time at my disposal; not having to be in any particular place at any particular hour, not having one’s days broken into small increments is wonderful. There are also, of course, the auxiliary pleasures of not having to grade papers, not having to attend committee meetings. It is basically a sense of freedom.

IY: What upcoming projects are you working on now?

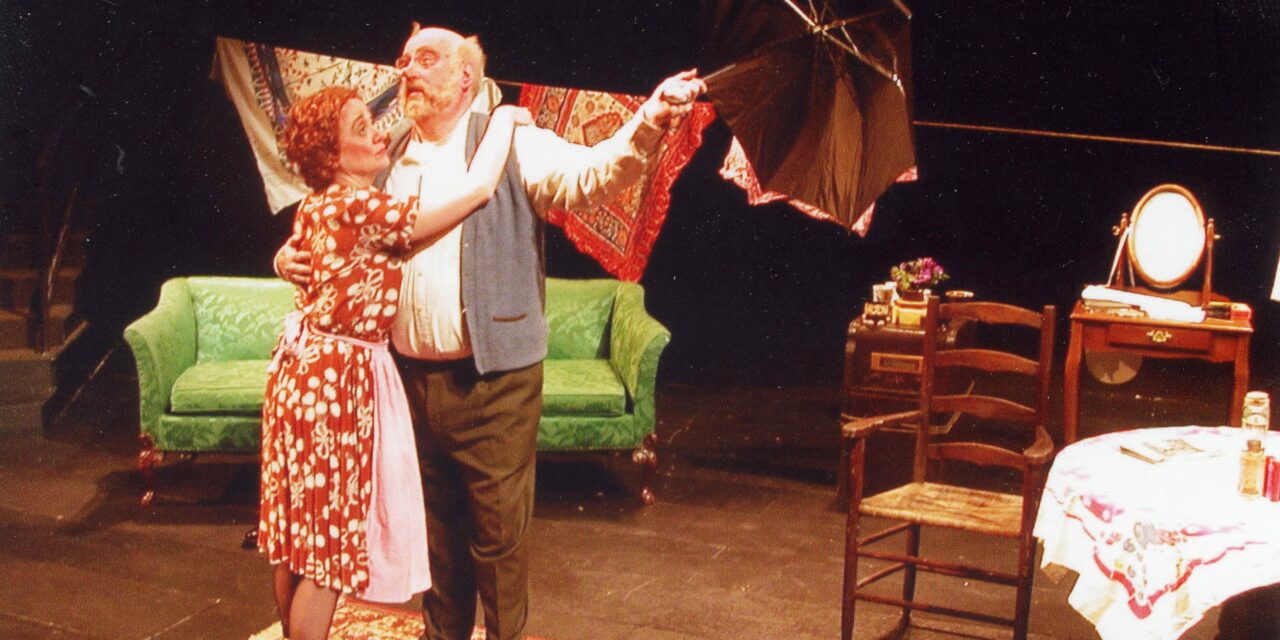

LS: About two years ago I started a major book on theatre and photography in the 19th century. I was working on it every day for a while, and then all of a sudden, I had to stop and write a number of conference papers as well as a piece for an anthology, and I found that I could not get back to the big project. At that point, I thought: do I need another magnum opus? The idea of tackling another massive book was not appealing at that point. So, what I am working on now is a variety of short articles, not necessarily for academic journals. As far as theatre goes, I am still working with Poets Theatre. That’s the point of being retired – I don’t set deadlines, I don’t feel under compulsion. I work on things as and when I feel like it. I’m not eager to take on another big commitment. I’d rather savor my present situation for a while.

IY: I was fortunate to study theatre iconography in your class several years ago. The digital landscape of this world has changed dramatically since then, let alone in comparison with the time when you were a student. How do you think the 21st-century saturation with pictorial materials changed the perception of theatre?

LS: Certainly, in the realm of research, everybody is taking shortcuts. People go to Google first, and that means constant recycling of the same information and misinformation. I am a traditionalist. I love going to the archive to consult the source. I am a great believer in confronting the original document, the original picture, which gets harder the more things become digitized. It’s crucial to any historian to open a window into the past. Handling original materials is much more direct and visceral than dealing with a digitized file. Not to mention the fact that digitized forms are often partial or inaccurate.

In theatre, there is far more use of electronic media on stage. Even when real human beings are performing, if a screen or a projection is on stage it’s going to monopolize the audience’s attention. This has to do with the nature of human perception. A living actor can find it hard to compete with a projected image. Designers are fascinated by technical innovation, so often discount what a live actor can do. Another thing, the audiences have changed. When audiences have grown up in with mediated electronic images, they don’t necessarily expect that they have to respond or give the actors something back. We also see this in classrooms or in lecture halls where the auditors regard a teacher or a presenter as a hologram rather than a fellow-creature, and therefore don’t feel the need to respond in any kind of immediate or easily perceived manner.

Another problem is, of course, that theatre now is not something that is easily accessible. People don’t grow up with it, they don’t go to see it as a common occurrence, so it becomes a special event. Ticket prices, certainly for large commercial ventures, are astronomically high. That’s why everything, no matter what, receives a standing ovation. There was a time when a standing ovation was reserved for something really outstanding. I wouldn’t give it to anybody but Maria Callas. But now the audience is not so much applauding the performance as applauding itself. “We had the good taste to show up, to pay for parking and dinner and this expensive seat, and we are damned if we’re not going to act as if this is the best thing since Sarah Bernhardt.” Audiences are not critical anymore. Not only don’t they have the experience to compare and contrast performances (how many Hamlets are they going to see in their lifetimes?), they also have this sense that “This has got to live up to the hype that brought us here in the first place.”

The film has the problem of a different sort of accessibility. When I came to Cambridge in the mid-1960s there were cinemas that simply showed nothing but art films and foreign-language films and movies of the 1930s and ‘40s, and did it on a daily basis. Every Harvard residence, every local church had a film society. You could spend your week seeing old silent movies as well as obscure foreign films. This accessibility is no longer possible. Yes, you can get much of this on disk, but you’re not seeing it on a big screen, where it is supposed to be seen, and you’re not seeing it with an audience. It’s a reduced experience. I can’t believe it when people watch things on their phones. As time goes by, the act of human perception changes. When people grow up with this as the norm they fail to realize that they’re not participating in the way the experience was meant to be perceived.

IY: Did film and television replace live theatre?

LS: it depends on what you mean by replace. Up until the 1920s, the live theatre was the dominant form of public performance, along with opera, ballet, circus, variety. And then movies replaced it as the most popular art form. This didn’t kill off theatre, but it segregated it, made it something a little more remote, special, perhaps more high-brow. This is still the case. The curious recent phenomenon is the addiction to well written and acted television dramas. I would say the contemporary television multi-part drama resembles the feuilleton, the serial novel of the 19th century, which many critics at the time thought was a low-brow or a philistine form of amusement.

IY: Which trends in the study of the performing arts do you find exciting?

LS: I am old enough to have lived through many different waves of dogma. When I was an undergraduate, the New Criticism was the hot thing in literature as was existentialism in philosophy. Since that time, I’ve had to deal with neo-Marxism, structuralism, post-structuralism, the new historicism, neuroscience, and a great many other trends. There were times when everybody who gave a paper had to mention Bakhtin and the carnivalesque. Or Foucault and power. You knew almost from the first paragraph what the conclusion was going to be. And the individual voice was drowned out by a requisite vocabulary. We are going through a period like this now when the totems are race, gender, and ethnicity. Nothing wrong with studying those. I happen to be a pioneer in the field of gender studies in theatre. Nevertheless, it breeds a sameness, the need to present your bona fides by showing that you are ‘woke.’

IY: I hope in the future ‘wokeness’ will be taken for granted.

LS: That’s right. Nowadays we take the ideas of Freud and Marx and even Foucault for granted, they are part of our spice rack. You put a little dash of this and of that, but you don’t make it the major ingredient in the dish. There is one trend I appreciate at the moment: the notion of translocality and global theatre. It gets us moving away from some of our more narrow concerns and allows us to view performance that moves from place to place and is transformed in the process. That excites me partly because in order to study this properly, you need at least a few languages. The provinciality of American theatre scholars, unpracticed in foreign languages, is an old story. Instead of shrinking as the world get smaller, our linguistic imperialism is in fact thriving. I always tell my students to learn foreign languages so it won’t be so easy for authorities to lie to them.

A problem of viewing foreign productions outside their culture is that they are shown out of context. I don’t know how to get around that; not everyone can go and see bunraku in Osaka. But even if you see it in Boston, without the Japanese audience and environment, it is still exciting and stimulating. The recent popularity of simulcast or recorded live performance should not obviate the encounter with the live.

As one studies the globalization of performance, it becomes apparent that it is essentially a capitalist phenomenon. When Peter Brook moved to Paris and formed an international company, his motives were largely aesthetic. Yet something like Cirque du Soleil and its ilks can entail commercialization, commodification and Disneyfication.

IY: You recently presented a paper at a Stanislavsky conference. What are your thoughts on Stanislavsky’s current place in the timeline of acting pedagogy?

LS: It is very interesting that most of the members of the Stanislavsky Symposium are acting teachers rather than scholars. They are using Stanislavsky pragmatically, reinterpreting, reshaping him in their own image, in the image of the kinds of students they have. The more they reshape, the farther away they get from the original Stanislavsky’s own ideas. (Admittedly, those were always in flux and difficult to be pinned down.) I sat in on a couple of workshops, and they were more like parlor games for acting students than anything that Stanislavsky would have thought contributed to creating a role. They seem to be forming an all-purpose actor in a vacuum, for these classes rarely ask pupils to address a given part in a script. What Stanislavsky was interested in, once the actor gets beyond a state of relaxation appropriate to creativity, was how to create a role or a moment in a play. He evolved different approaches: early on he wanted the actor to summon up his own emotions, then he wanted the actor to imagine the character’s emotions, and then he moved on to physical action that would presumably promote or stimulate the emotion, but it was always in service of a script.

In the beginning phases of any kind of performance, you have to learn basic skills: voice, body, improvisation, any number of elementary means of stage expression. Once you get beyond the basics, one approach is to interpret a script or scenario, another approach is for the actor to devise the scenario. In both cases, it all comes down to being very specific.

One of the things I used to like about Russian actors was that what they did was always nuanced, focused on the detail that changed from moment to moment. American actors tend to apply an overall wash of emotional color and stick with it. They rarely change or grow over the course of a performance; they may get louder or softer, but that’s not the same thing as being mercurial.

IY: Do you find that the students changed much since you began teaching decades ago?

LS: Yes, and I think it is partly because of what is expected of them. We are now living in an age (and I’ve observed it in this department) of the helicopter professor, like the helicopter parent, who hovers all the time, is always watching out. There is a sense nowadays that undergraduates are so intellectually and emotionally immature that they need to be guarded, taken by the hand and walked through an experience, given trigger warnings. “You may hear something that may scare you, or something you won’t like to hear.” Students need to be mentally adventurous. They must not be protected from any kind of speech. They must not be forewarned that something is going to upset them. They must discover these things for themselves, and come in contact with a wide range of opinions and concepts. Unfortunately, these days students react to this protectionism by mistaking outrage for critical thinking and use indignation as a weapon to occupy the moral high ground.

As to graduate students: When I was coming up, finding a job was not that much easier than it is now, but the situation was not considered. Now because jobs in the humanities are fewer, education is being swapped for “professional development.” Departments are turning into employment agencies. I have a wall full of teaching awards, but I never took a pedagogy course in my life. Everything I learned about teaching I learned by being first a student and then as “on-the-job” training. Because when you’re behind a desk from the age of five, you very rapidly develop a critical sense of who is a good teacher and who is a bad teacher, who is getting through to you and who is turning you off. And if you go into teaching, you have this enormous amount of past experience to draw on. This is something that should happen organically. I think that requiring graduate students to take full-semester pedagogy courses is a waste of time. It could be better spent exploring their discipline, improving their research and writing skills.

I find that more and more students lack cultural background. They may have read some plays but they haven’t developed a writing style by reading great prose, they don’t know poetry, even readily available films – so their range of allusion and reference is a stunt. There’s such a limited knowledge that they bring to their classes. I actually had a graduate student in Theatre Studies who had taken comprehensive exams but had never read Macbeth. The fragmentation of the canon makes it harder to communicate.

Memory is a muscle and it needs to be flexed. I probably sound like the oldest inhabitant but when I was a kid I knew reams of poetry by heart, and lyrics to songs, snatches of speeches and dialogue, stories from mythology and folklore, even complicated shaggy-dog stories. I could recite them, sing them in the shower, relate them in class. Of course, as a child actor, I had to memorize lines. No one bothers to try to memorize anything of substance any more. That’s a real loss.

IY: Speaking of actors: what is your opinion on graduate students pursuing graduate academic degrees when their primary focus had been acting and performance, as opposed to research.

LS: That has changed too. When I first started at Tufts, students who were taking a master’s degree were primarily aiming to be actors and directors. This was before the MFA became common. We also allowed MA students to stage thesis productions. However, once MFAs became available those who aspired to a career in the theatre sought them, and our applicants became more focused on scholarship. However, since I grew up leading a rather schizophrenic life, one foot in academe, one foot on stage, I think it is a great thing when people who come for an academic degree have a background in practical theatre; it’s a step up when they are hired as junior faculty. They can direct, teach acting classes, as well as theatre history. I also think that while they are still in class, it is a great safety valve for them to participate in shows, if they can juggle it all. For many years, we had graduate students perform in faculty productions, and they made the cast a very rich mix. It’s a pity that now they seem to be so overworked and overburdened they don’t have much opportunity to get near a stage, unless they’re assigned to direct, usually to build up their resumés.

IY: What favorite moments from your career as an educator would you be willing to share?

LS: Obviously the happiest moments are when a seminar is going really well or students in a lecture course are very responsive. Specific moments in the classroom are those when I could see an idea taking shape or a mental light bulb turning on. Specific moments in the theatre are those when a cast comes together as an ensemble and an audience unites in laughter or awe. Looking back on a lifetime of teaching, what gratifies me is to see so many of my students carrying on teaching, researching, publishing their own books and articles. And those who aren’t in academia pursuing careers in the performing arts in some other way. Whether or not they’re aware of it, they are carrying and handing on my intellectual DNA, so it’s like watching generations of children and grandchildren succeeding in the world.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Irina Yakubovskaya.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.