Get inside a woman’s head and, by understanding her, unravel the mystery of how the world works. Theodoros Terzopoulos, whose play Nora (Attis Theatre) opened the MITEM festival as part of this year’s Theatre Olympics in Hungary and which has resonated around the world, proved once again to be a master of this art. This first note of the program, entitled Nora, seems to set the tone for the festival’s forthcoming program. In it one hears a sharp cry of pain, one sees the beauty of despair, one senses the energy of time playing with man and man subjugating time in the proposed circumstances of the theatre. It’s a very striking note of the program, the sound of which will not be easily drowned out. But despite the word Olympics – there is no spirit of competition or rivalry here. On the contrary, the program is not divided, but unites the masters of theatre in a single impulse to make a statement in the deafening agony of the present day.

This is not Ibsen’s Nora, but Nora by Theodoros Terzopoulos. The Norwegian playwright’s groundbreaking play is here stripped down to an “unlove triangle” composed of Nora (Sophia Hill), her husband Helmer (Antonis Myriagkos) and her creditor Krogstad (Tasos Dimas). The text is abridged but expanded, stripped of superfluous material and filled with personality, the text has been stripped of its textual feel and the feminist agenda that has stuck firmly to the piece, about a woman who decides to leave her husband and children to sail off on her own in search of herself, has been removed. Most productions heroized Nora or painted an image of the victim, while claiming to put the heroine – a collective image of women – first. Theodoros Terzopoulos did not argue or argue with a string of previous versions of this play. This director-author, who has subordinated the huge antique drama to his directorial gift, has not needed to prove anything to anyone for a long time. The author, who has subordinated his gift of directing to the immense amount of ancient drama, no longer has any need to prove anything. There are only two colors – black and white – but this doesn’t limit the spectator’s perception of the performance; on the contrary, it extends the palette. It is a laconic, lapidary (as if carved in stone) canvas, which, with the director’s sharp thought and look, mercilessly cuts an uncomfortable truth about the nature and causes of human passions and actions, about theatrical lies and the theatrical truth of relationships, about the hidden and obvious, the dawn and dusk within us all. Theodoros Terzopoulos does not spare the spectator or his actors, nor does he spare the text. Thus the play, short in time, turns out to be both an intoxicating and extremely painful experience, which everyone will wish to live through.

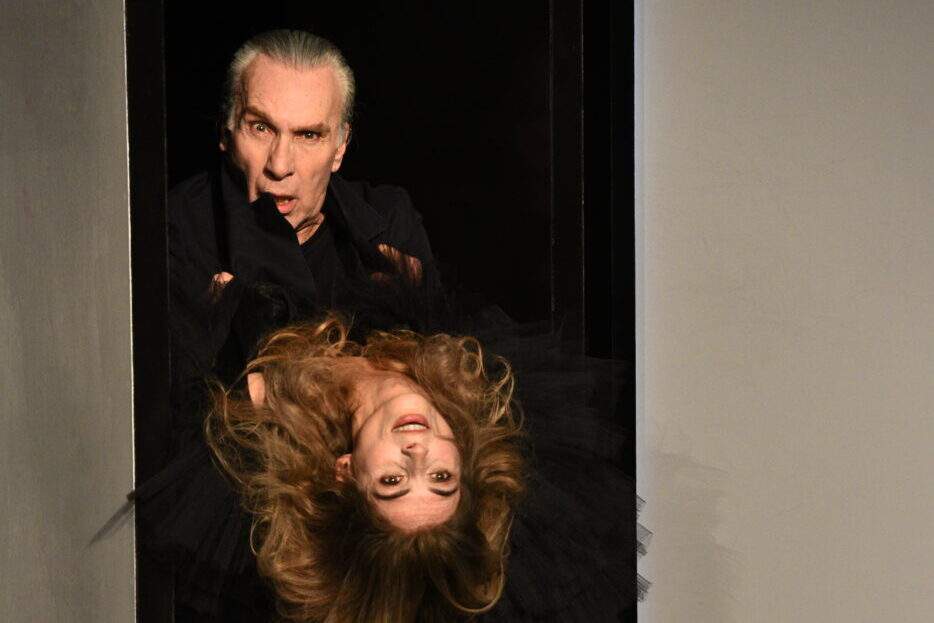

The play unfolds in a space of black and white revolving door-windows (setting installation: Theodoros Terzopoulos). We observe life behind closed doors, revealing the imaginary nature of everything that is put out in public. Imaginary family happiness, opinions, declared thoughts, morals, religion etc etc. Behind the bright side, however, there is always a dark side, behind the good intention – hell. Infernum continuum sounds from the stage. It means in Latin. Continuous hell. I would like to add – Present continuous hell. Sophia Hill, who brilliantly performed Jocasta by Jannis Kontraphouris directed by Terzopoulos, reaches lofty heights of acting and magnetism in Nora. She performs the female solo not just with her voice but with her whole body, every gesture and facial expression. Here even an actress’ hair becomes a means of artistic expression. There is nothing casual or improvisational here. Everything is subject to the strict actor’s corporeality, which is at the heart of the Theodoros Terzopoulos directorial method and school. At the same time, the actors are certainly not crammed into the seemingly compressed and bottomless, if you think and feel about it this way, space of the director’s idea.

Nora’s hands – her palms – and her open elbows become the main expressive means of the play. The score of her gestures seems to be elaborated in every detail. Many mise-en-scenes are based on the interplay of the actors’ hands. The hands envelop, tap out, greedily search, try to escape, cry out, plead, squeeze etc etc. The hands express that which the lips are silent about or refute what comes out of the lips. The hands here are convulsive and express the fever of the soul of Nora, in which Sophia Hill exists. In the black-and-white, piano-like keys of the space, the hands are played and the play itself looks like the handiwork of a jeweller of the very highest order.

In Ibsen’s play, Nora is either a lark or a canary, while in Terzopoulos she is a black swan. The black feathers of her garb, overshadowing the man, merging with the darkness of the stage, are a vivid and piercing image of the performance, combining the features of installation and performance art. “Black Swan” is like a symbol of the era in which we find ourselves, an era of unpredictable, life-changing events. Nora’s act is not endured by her, she is not pregnant with the thought of leaving her family and the decision is like thunder to everyone. In Terzopoulos, Nora, the heroine of A Doll’s House, finds herself a puppeteer in the form of a puppet from the start. We see before us a victim of the age of consumption and the false pursuit of imaginary ideals, who is at the same time a manipulator and a pretender. This Nora, who at one point seems to be the one for whom the world is a supermarket. A scene describing the purchases, a continuous list of titles that Nora has supposedly purchased, concludes with the recitative “Everything is for me!” The world for Nora boils down to an assortment of goods and services. Cream, lipstick, Botox and vaccines. In Ibsen, Nora spends money for the family, in Terzopoulos, Nora as a universal measure of all things, as a symbol of ego, as an illustration of the insatiability of man who does not moderate his desires. Behind this infernal line of products, man is ultimately lost. He becomes a random combination of needs invented for and imposed upon him. Nora’s departure in the finale, when she closes the door behind her, is a departure from the doll world into the real world, the world not yet born in her mind, the world of the unknown. But after all, our civilization was once preceded by chaos. If there is darkness (the darkness of the stage in this case), then there is hope of light and in a sense enlightenment.

Nora here is the measure of all things (like the Protagoras formula). She is focused upon the outward appearance, and the performance proves conclusively that which such anthropocentrism and focus on the material side of life can lead to. Unresolved inner issues, tonally disguised deals with conscience – all of these eventually inevitably catch up and demand payment on the bill. And the moral debt turns out to be the most expensive of all the heroine’s debts. The heavy form of the insatiable Nora’s frivolity leads to suffering, but through it to liberation.

The entwinement of hands here is like the entwinement of fate. Men’s hands squeeze women’s hands. The woman’s fingers braid the man’s, striving to get what they want. Terzopoulos has more gestures than words, but the greater the significance and weight, sounding from the stage. The characters dance to the tune of Johann Strauss II – The Blue Danube Waltz and embrace a living hell. But this hell is paradoxical in the performance – Krogstad utters: “Infernum continuum – Miracle”. A miracle of hell that is not as frightening as reality, or a miracle in hell as a glimmer of hope – it’s up to each audience member to decide.

Attis Theatre: “Nora.” PC: Johanna Weber.

Nora, despite its dynamic and whirling emotions, has a strikingly antique statuary. The Norwegian drama here rises to the catharsis of ancient Greek tragedy. Through the purification of the text there is also a purification of the characters. What remains is what is most important in them, all that is painful. And when all the layers and false projections have been removed, the performance reveals the secret writing as if through a palimpsest. This Nora suddenly turns into a performance about hell and the miracle of theatre as an art that is animated with life. In the same way that Nora sheds her falsehood and lies, the actor has to overcome technique and the arsenal of professional acting tools to appear to the spectator as a performer – not as an actor in a role, but as one who lives through it on stage. The stage of the theatre is more honest than the stage of life. From props and domesticity (that very list of Nora’s purchases), the play rises to the pinnacle of being, from well-being to goodness. Just as Nora’s second breath and lust for life opens up, the breath of sacred action, of ritual, of human nature embracing the nature of art, is palpable in the performance. And this is the paradox and uniqueness of Theodoros Terzopoulos theatre, in which post-dramatic features are combined with the primordial nature of theatre ritual. This is reminiscent of what director Tarlan Rasulov formulated in his program text Manifesto XXL: back to the future of theatre. Here the sacredness of theatre is restored, stripped of its false and inconvenient pathos.

Nora Theodoros Terzopoulos and her Triangle of sadness turns out to be a theatrical essay by the director about men and woman, individuality and crowd, word and deed, egoism and sacrifice, reason and the unconscious, about the mirror of the stage and the mirror in which we often fail to see ourselves. It is a spectacle of fortitude and obsession, of peak emotion and humility, of unity and confrontation of body and soul, of minimalism and fullness.

Attis Theatre: “Nora.” PC: Johanna Weber.

The production reveals the fragility of a world that is crumbling before our eyes, something we understand so well today. In it, we grasp onto whatever categories seem stable to us – faith, tradition, morals, norms, conventions and rules. But even these are not immune to disintegration. Maskless faces suddenly turn out to be walking social masks whose guts are dead. And only theatre can breathe life into that which seemed to have faded into obscurity.

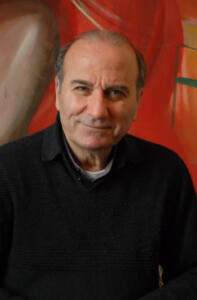

Theodoros Terzopoulos. PC: Johanna Weber.

The performance was followed by a meeting with the director to launch his book The Return of Dionysus, translated into Hungarian. Other participants in the book launch included András Kozma (translator) and Zsolt Antal (Deputy Rector of the University of Theatre and Film Arts, the publisher of the book, and head of the Antal Németh Institute for Drama Theory). A truly important event not only for the book world but also for the Hungarian theatre world, The Return of Dionysus is dedicated to current issues in contemporary theatre: what is body, energy, breath, word. It analyses key concepts such as passion, grief, emptiness, enchantment. It is a textbook for actors wishing to master Terzopoulos’ original method, which is based on the idea of deconstructing the body in order to release latent energy and recreate the archetypal body as the basis of the human essence. In this way, Theatre Olympics becomes a point of assembly and attraction for this year’s vibrant and important cultural events in Hungary, with a perspective – for many years to come.

Theatre Olympics is just getting started and its program is full of big names and many lesser known, but promising theatrical experiences. Not just limited to stage projects, it incorporates film and art, literature and dance. But most importantly, it once again beckons the viewer into the magical world of theatre, to which some have never managed to return, after a prolonged pandemic pause. This is the long-awaited and truly enduring Theatre Olympics, from which The Theatre Times will continue to introduce its readers to new and interesting productions. On the 27th March, Theatre Day, a road movie project was specially launched which tells the story of the journey of the theatrical mask donated by Theodoros Terzopoulos to the National Theatre and the 10th Theatre Olympics. I hope this mask will bring happiness and peace to all participants and guests and to all those who follow theatre.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Emiliia Dementsova.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.