As theatres reopened after the summer recess, the plays on offer in the Spanish capital were dominated by recreations of the country’s past. As with much cultural production, theatre performs an important role in forging narratives surrounding history in a society in which accounts of Francoist dictatorship and subsequent Transition to a monarchical parliamentary democracy remain bitterly contested. The hottest ticket in town was for the return of El bar que se tragó a todos los españoles [The Bar That Swallowed all Spaniards] to the Centro Dramático Nacional (CDN) [National Dramatic Centre] following a successful national tour. Inspired by real events, the play tells the story of a young Navarrese priest who, in the early 1960s, leaves the Catholic Church to become a travelling vacuum-cleaner salesman in the West Coast of the US. Beyond the anecdotal value of this attractive hook, the tale provides a gateway into wider questions surrounding the issues raised by the monopoly exercised on education by the ecclesiastical authorities during Spain’s dictatorship years.

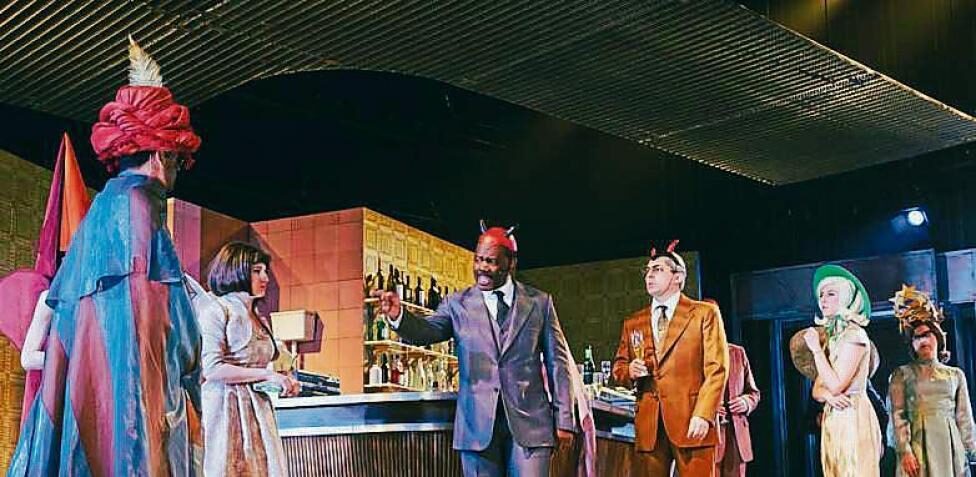

A semi-autobiographical production staged by the CDN’s artistic director, Alfredo Sanzol, El bar que se tragó a todos los españoles opens in a deceptively naturalistic barroom setting with a young woman struggling to write a play. Entering into conversation, she confides her fears with the sympathetic barman that either she will be incapable of doing justice to her characters’ experiences or else the play will go off in a thousand different directions. The segue into the principal narrative occurs when the barman offers to lend a helping hand by recounting some hidden chapters in her father’s life, the clear subtext being that Spaniards too often ignore their own family histories. In the program notes, the forty-nine year-old Sanzol writes that his father, who left the priesthood in the early 1960s, was full of stories but never spoke of how and why he returned to secular life. The result, by implication, is an attempt to grapple with this domestic drama in a lavish production that invites comparison with Tom Stoppard’s latest play, Leopoldstadt, in which an ensemble cast also take on multiple roles. Unfortunately, however, Sanzol’s over-vaulting ambition succumbs to the pitfalls outlined by the budding fictional dramatist in the play’s initial framing device.

The audience is transported back to the post-Civil-War period when the academically-gifted twelve-year-old Jorge Arzimendi from Pamplona (as is Sanzol) leaves his family after his parents are reluctantly persuaded that a seminary will provide him with the best opportunities for later in life. If joining the priesthood was, for many Spaniards, a matter of social advancement more than spiritual conviction, the increasingly consumerist turn of late Francoism and the more liberal doctrine of the Second Vatican Council threw up a new set of material and metaphysical questions. Aged thirty-three, Arzimendi headed to the US in 1963.

Melding real-life with fictional incidents, the on-stage Arzimendi begins a new life in the United States where he loses his virginity, becomes heir to a small fortune in Texas and, in a running gag, keeps on bumping into people also from Navarra. Music (e.g. the use of country songs in Blue Moon) is a privileged signifier, whilst some semblance of continuity is retained through effective set design and transitions between scenes that provide the backdrop to different bar and living-rooms settings. Less successful are attempts to further expand the socio-political landscape. At least on the night of September 21, the actor Jimmy Roca, born in Badajoz and of African heritage, was the sole non-white person in the sold-out theatre located in Lavapiés, one of Madrid’s most multicultural neighborhoods. Amongst the roles performed by Roca was Martin Luther King who, somewhat incredulously, is present at a fancy-dress party to which Arzimendi, after being told that the sartorial code involves blacking up, turns up as Saint Balthazar. Amongst the North American guests, no attempt is made to disguise their whiteness. There was no rationale to the scene beyond providing a pretext for the Reverend Luther King to expound on why it is offensive to appropriate the skin of another race, a monologue rewarded with spontaneous applause.

Jorge returns to Spain after falling in love with Carmen, an employee of the state telephone company he meets in the US where she is visiting to improve her English. Sanzol’s unfortunate tendency to over-explain plunges new depths when Jorge and Carmen meet for a date in a café near Franco’s principle residency, El Pardo, and bump into a Communist former-exile and painter Arzimendi met on his travels. The disillusioned older man complains not only of being forced to paint celestial ceilings for the Caudillo’s home, but also that there are no signs of the agreed payment. This provides a pretext for an anachronistic prophecy about how justice will not be done, the dictatorship’s pillaging will go unpunished.

Irrespective of my reservations, El bar que se tragó a todos los españoles won “Best Production”, “Best Play-Text” and “Best Set” at the annual Max Theatre Awards. On the night I attended, the actors were rewarded with one of the most enthusiastic standing ovations I have ever witnessed. The melding of the personal and the political clearly touched a nerve, whilst the sketch-like structure of many individual scenes – culminating in a farcical sub-plot set in the Vatican where physical torture is eventually employed once financial bribes prove insufficient for a corrupt Cardinal to sign the relevant papers from the Pope to give Arzimendi dispensation to leave the priesthood and marry – functioned to retain the sold-out audience’s rapt attention over a marathon three-hour (with no proper interval) performance.

Atocha: El revés de la luz [Atocha: The Other Side to the Light], at Teatro del barrio [Neighbourhood Theatre].

Many of the Teatro del barrio’s productions have individually and collectively questioned the so-called “regime of 1978” to suggest that the roots of many of Spain’s current monetary and moral ills can be traced back to the forging of an imperfect democracy predicated on a combination of market capitalism and the amnesty of crimes committed during the nearly forty years of dictatorship. Written and directed by Javier Durán, with the collaboration of Alejandro Ruiz-Huerta (the sole surviving victim of the massacre), Atocha: El revés de la luz seeks over seventy minutes to provide historical context for and to recreate the tragic events of January 1977 with a cast of five taking on multiple roles. Adopting the meta-dramaturgical device of an on-stage Ruiz-Huerta struggling to recreate his student days for the memoires he has been commissioned to write in the late 1980s, the production substitutes the frequent romanticization of the Transition for an arguably idealistic view of the Francoist opposition. There are references to the iconic concert by protest singer Raimon at the Complutense University in May 1968, and quoting Marcuse or Marx is presented not as intellectual grandstanding but as a commitment to gaining the theoretical tools to topple the regime. True to the historical record, the future-lawyers come from diverse backgrounds, including a migrant from the Andalusian town of Jaén who prides himself of being able to predict the weather. They gently rib the fashion sense of public school boy Enrique Ruano, whose father belonged to the Francoist parliament, a family connection that initially saved him from receiving a criminal record but was ultimately an inadequate defence: killed whilst under arrest by the secret police, the extra-judicial execution was camouflaged as suicide.

After Franco died in his bed, many Spaniards told their children, and each other, frequently apocryphal tales of running in front of the police, nicknamed “los grises” (the “grey ones” referring to both their uniforms and drabness as human beings). Atocha: El revés de la luz foregrounds camaraderie over intimidation when the students run between a corridor made up of truncheon-wielding bullies, but the depiction of the human costs of brutality is the antithesis of nostalgia. Ruano’s girlfriend, Lola, trained as a lawyer and was a survivor of the Atocha attack, the on-stage perpetrators of which were the period sun-glasses that have become a metonym for Francoist bully-boys such as “Billy, el niño” [Billy, the Kid]. As is shown in the cinematic documentary, Billy (Max Lemcke, 2020), the infamous ex-policeman and torturer – who was given a medal for his services to the state during the democracy, and continued to receive a hero’s pension until his death from Coronavirus – provided the inspiration for the most macabre of the characters in Bardem’s Siete días de enero film.

Spain’s arrested democracy is diagnosed by the characters on stage who, following the legalization of the Communist Party, anticipate that the Transition’s radical potential will be diluted as individuals become institutionalized. A debate surrounding the possibility and desirability of changing the system from within descends into an on-stage shouting match, symptomatic of an inability to know how to bring the play to a satisfactory close, whilst the fetishization of this pre-Constitutional moment flatters the protagonists and audience alike.

Although there are solid grounds for calling “the regime of 1978” out for its smug complacency, let he without sin cast the first stone. As with much of the Teatro del barrio’s output, the piety of Atocha: El revés de la luz relies on a complicit audience, evangelical in their consensus over the original sin of post-Franco Spanish democracy. Following the matinee performance on Saturday 25 September, there was a round-table discussion featuring the cast, Ruiz-Huerta and Cristina Almeida, one of the prosecution lawyers in the Atocha case. Whilst the play had touched on issues of gender – a woman questions the fictional Ruiz-Huerta over his claim that there was no distinction in the struggle between men and woman – this was brought more to the fore in the questions from the audience to Almeida, who recalled being a practicing lawyer but, on being prosecuted for her dissident activities, not being allowed to represent herself because, as a married woman, she was legally under her husband’s tutelage. In the 1980s, Almeida was one of the founding members, and later MP, for Spain’s post-1978 Communist Party, the Izquierda Unida [United Left]. With warmth and humor, she summarised her response to the play in relation to her long-held belief that she was never clear what it means to be on the left, but that she was damn sure she could not abide the right. She also made the case that fighting the good fight can be harder in democracy, as the enemy is not so clearly defined as under an oppressive dictatorship.

N.E.V.E.R.M.O.R.E., at the Centro Dramático Nacional (CDN) [National Dramatic Centre].

Depicting the personal and political as inextricably linked in a close-knit quasi-feudal rural environment, the six cast members take on multiple roles in a visually imaginative and dynamic production. The government-sanctioned local media initially sought to present the “Nunca Mais” platform as being the work of loony radicals, but the carefully delineated accents of people involved on the stage suggest it transcended politics to become a community response to a man-made tragedy. A young woman speaks of how she realized her PP-voting father was a good man when, on comprehending the scale of the disaster, he offered assistance. Links are made to the present through reference to the protective wear used in 2002 being resurrected two decades later with the outbreak of COVID-19. In general, however, the production perhaps limited its appeal by having most resonance for those with first-hand memories. An arresting scene featuring an assembly of black umbrellas evoke iconic images of demonstrations from the time, whilst the panicked radio-control calls (which employ historically documented dialogues) echo MayDay a short film made by Galician writer Manuel Rivas for ¡Hay motivo!. This portmanteau protest film denounced the PP who, shortly afterwards, were ousted from the national government after deliberately misleading the electorate over the perpetrators of the 2004 Atocha Train bombings by Islamic terrorists.

The great survivor, Fraga nevertheless retained control of the Galician Parliament. N.E.V.E.R.M.O.R.E. shows how flooding the affected area with money and a still unfulfilled promise to open a state-run parador hotel to boost tourism and the local economy allowed the PP to escape from the political and ecological disaster largely unscathed. Over the course of the two-hour performance, the toxic combination of aggressive global capitalism and quasi-feudal local paternalism is brought to the fore with an innovative hybrid of verbatim-style dialogue filtered through a post-dramatic sensibility for which Chévere have long been a point of reference in both Galician and Spanish theatre. Systems of working rather than the workers themselves are indicted through the aurally immersive scenes (which, impressively, are generated by the actors live on stage rather than being reliant on pre-recorded materials) of unsuccessful attempts to communicate about what should be done as the ship is sinking. A cacophony of voices speaking in different tongues constituted a dystopian Babel, compounded by the violence of the sea and faulty equipment that, much like the workforce, had been (out-)sourced from and to the most competitive tender, safety a secondary concern.

The Galician-born General Franco was fond of describing the Spanish nation as one of the world’s great spiritual reserves, whilst an infamous tourist slogan created by Fraga boasted that “Spain is different”. Since the late 1950s, however, aspiration replaced austerity as the country became an increasingly European-style consumer society with a burgeoning middle-class. Integration into the European Economic Union in 1986 was widely seen at home and abroad as validation of Spain’s successful Transition. Since the economic crash of 2008, more attention has, however, been paid to the collateral damage of this collective sprint into (post-)modernity. Irrespective of their temporal, geographical and spatial difference. Atocha: El revés de la luz, El bar que se tragó a todos los españoles and N.E.V.E.R.M.O.R.E. all offer tribute and testimony for too-often forgotten human(e) tales. The dominant theme of the contemporary Spanish stage reveals a pressing need to suture the personal and political wounds of the past. Drama could potentially perform a galvanizing role in this healing process, but a weakness for didacticism amongst practitioners and audiences alike runs the risk of relegating a potentially vibrant living theatre to the realm of the deathly echo chamber.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Duncan Wheeler.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.