A guitar-strumming Kuchi opened the floor with her somewhat hoarse yet unique voice. The strings of her first song came off like a bad rendition of India Arie’s Complicated melody, but by song two, her soulful “A hurumgi nanya” refrain enjoyed some audience participation. Then Dike Chukwumerije took to the stage to performance poetry bliss.

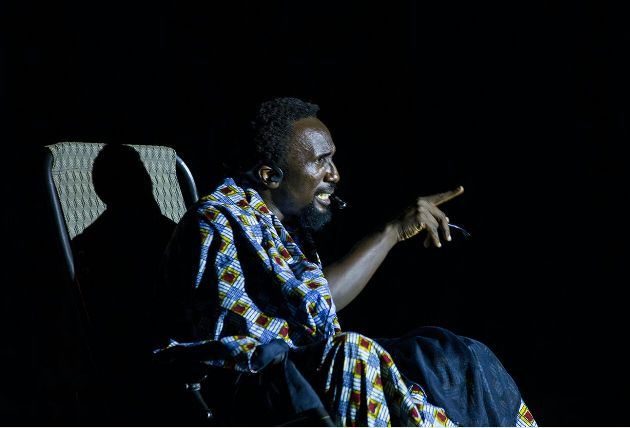

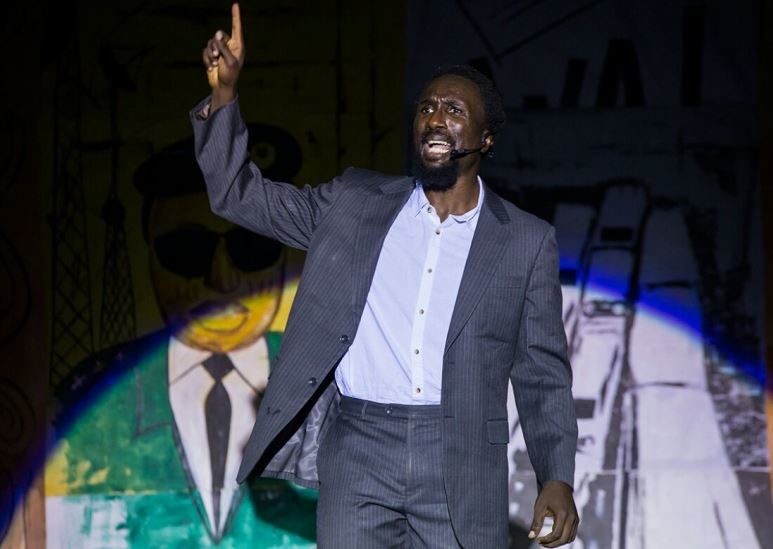

Imagine that your great-grandfather walked into the room, and you asked him what year he was born–quirky right? This was how Dike Chukwumerije began the Made In Nigeria performance that Friday at the Shell Hall of the Muson Center.

I was pleasantly surprised as Dike Chukwumerije transformed into that great-grandfather, who in response to the youth’s question says that he was born on the night his father was taken away—in the time of Ntiji Egbe, in the year the white man came to recruit his ancestors for war in a faraway place. The year is 1914, and the month most likely is August, but the old man insists that he was born on the first day of the first month of that year.

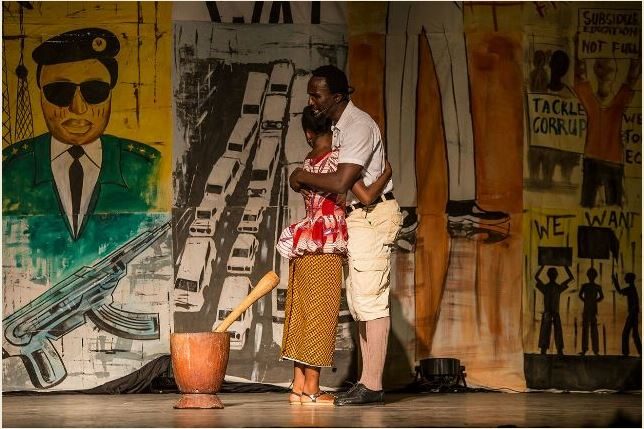

At a mother’s wise words: “You may choose to be born at the end of your father’s life, or you may choose to be born at the beginning of yours. Choose wisely,” an ominous gong sounded in my head, thus loosening certain hitherto taut knots. This 120-minute journey through 102 years was to be an exercise in identity and purpose.

Within twenty poems, Dike Chukwumerije delivered history in a tight capsule, washed down the gullet of our consciousness with dance, drama, alternating doses of humor, and music that traced time, and brought the settings alive.

In sometimes serious and sometimes light-hearted verse, Dike held the Lagos audience captive, as he painted Nigeria before our eyes. The wisdom of Eyo Ita, Nnamdi Azikiwe, Tafawa Balewa, and even Herbert Macaulay colored the steps we climbed under the tutelage of Chukwumerije.

To remain untouched by the stories spun in this narrative of one score poems, was to be insensate. And there were no robots in the audience that night.

But there was laughter too. Early on, we learn from a character in Chukwumerije’s novel, Urichindere of an alternate story of the coinage, Nigeria. A European, upon becoming governor-general of the newly amalgamated territory in need of a name, decided to name the country for what he could remember of his Igbo lover’s moans. Thus Nna, jieya (Hold on for a little longer) became NIGERIA.

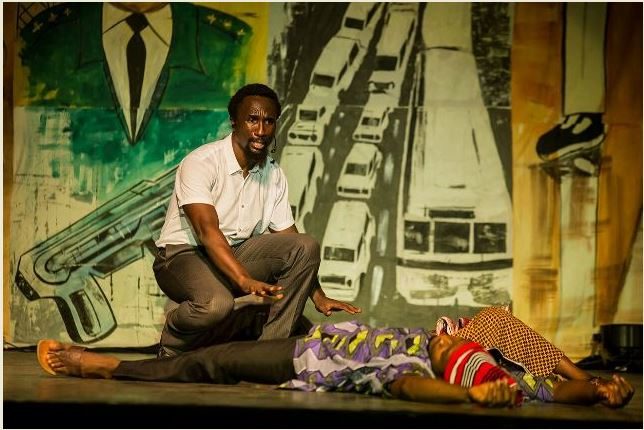

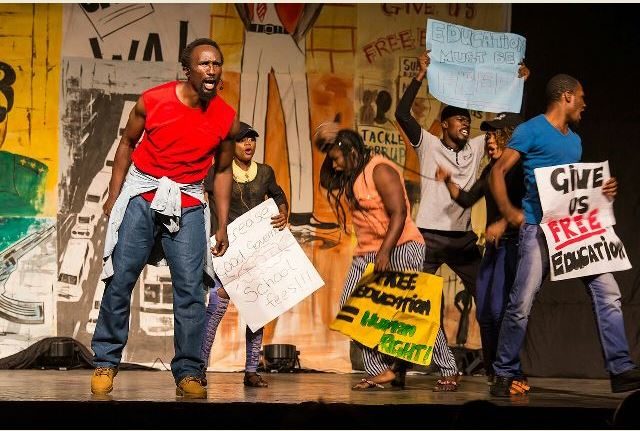

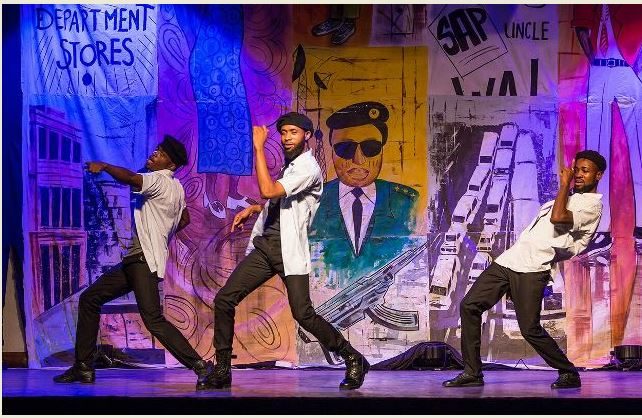

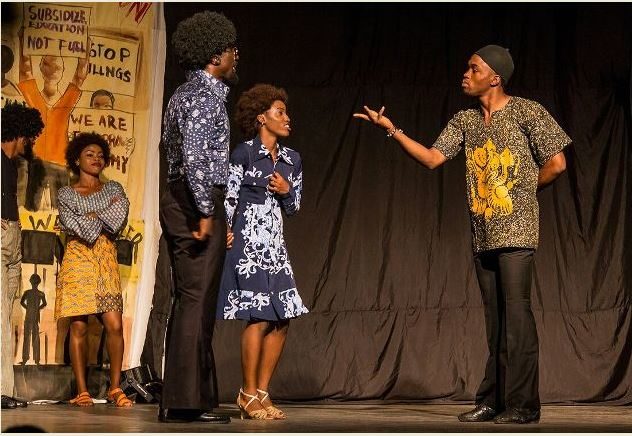

From a love story in the ’70s which ends at the start of the civil war, we experienced the ’80s–coup after coup—and the reality of our retrogression as a country fills our hearts as we encounter student activism through Dike’s shouts of “Comrades, comrades, I want to talk. I want to elucidate…! I want to pontificaaate…!”

The soldiers who break up this protest danced Shoki on the stage, but that took nothing away from the seriousness of the scene.

As the scenes unfolded, mine was surely not the only head shaking in disappointment, neither was mine the only lips curled downwards in the hall, but as sure as heaven, my lips reversed downwards when Chukwumerije came on stage again to render a funny poem about how a Nigerian mother prays for her first son.

In the course of the evening, I remembered a conversation that almost turned into an argument on social media a few years ago. In the heat of the attacks by Boko Haram. A lot of Southerners had clamoured for a split in the country, “So the Northerners can enjoy their North, and let us have peace, since they see us as infidels,” Dike, ever the voice of reason, argued that people would suffer more in the event of the country breaking, thus it was better we remained as one Nigeria. My present stance on the matter is this: we need to get to the point where we see ourselves as one, as equal partners in this contraption called Nigeria, we need to have an ideal to work towards, together. Not as Igbo, Yoriba, Ibibio, Hausa, Kanuri, Tiv, Igala or Ogoja–but as Nigerians. But I fear that this may take us another fifty-six years.

Indeed, these were protests and political poems spiced with song, dance and some playful life and love poems.

When in speaking about Nigerians waiting for their turn to become the oppressor after years of being oppressed, Dike said: “Let’s talk about change but don’t you dare become it.” I had no doubts that beyond a creative history lesson, this was a call to awakening, it was not just a chronicling of our existential realities, it was a call to action, it was daring us to be different, so as to have a better Nigeria. Beyond rhetoric, Made In Nigeria was daring us to hold our leaders accountable.

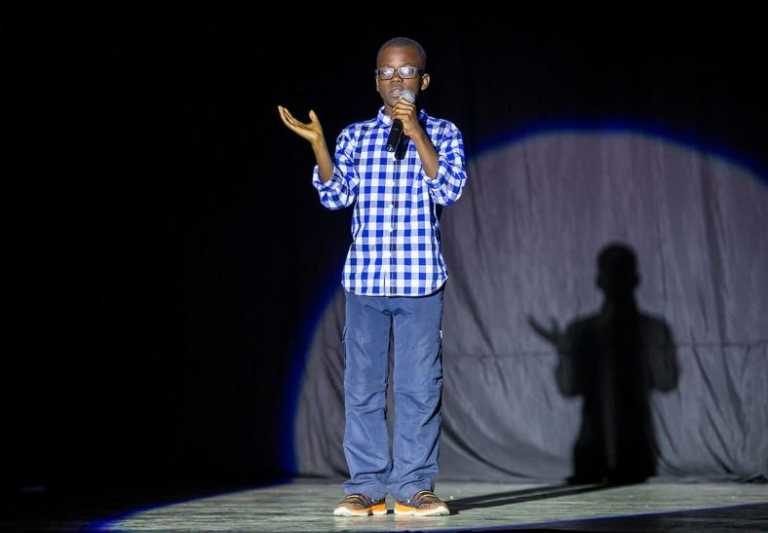

Two children—a boy and girl, got the chance to grace the stage too–a good opportunity to showcase the winners of a competition that Chukwumerije had organized. Kelechi performed Dike’s The Nigerian Dream, right after Ariel Adamu sang both stanzas of the National anthem.

The last poem, Keep Marching On, was dedicated to Herbert Macaulay, who watched on from vantage position on the backdrop, no doubt proud that this young Nigerian was doing his bit to keep alive the Nationalist’s ideal.

Dike Chukwumerije, Kronk Dance studios, and the 15-man cast and crew who came all the way from Abuja to perform Made In Nigeria deserved no less than the standing ovation they got in Lagos.

Dike would later say that Lagos validated him that night. I daresay nay, Lagos was given a necessary jolt of awakening, the one every Nigerian city needs.

This post originally appeared on Olisa on December 20, 2016 and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by The Theatre Times.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.