Beckett would have been unhappy. Hamm’s feet sticking out from under the blanket, and in white slippers at that; Nagg and Nell don’t live in trashcans close to each other but in transparent coffins, like in the mortuary; and Clov doesn’t hobble, doesn’t walk rhythmically precisely six steps from window to window, but rocks nonchalantly on his feet and isn’t even a man to begin with!

Beckett is, first of all, a bridge between two traditions, English and French. He thought and wrote in both languages. He also felt close to the German literary tradition, especially Goethe. From the Spanish-speaking one, he chose Borges and Paz, although they don’t come from the Iberian Peninsula itself. Thus it would seem he never had too much in common with either Poland or Spain. There was, however, a certain intimacy, a sense of empathy. The fate of the two countries was something he cared about. The 20th century left them scarred. They suffered a great deal of injustice. Like Job. And Beckett always extended a helping hand towards the wronged.

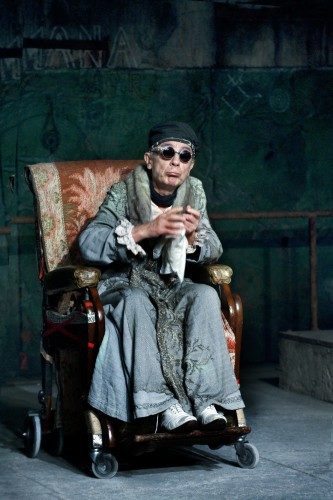

Endgame, dir. Krystian Lupa, Teatro de La Abadía. Photo: Ros Ribas

Whence the punishments? The question intrigued him and he asks it in Endgame. What’s interesting is how he goes about finding the answer. This search doesn’t take place in the text itself but outside of it, between words. Though we could also think that Beckett has designed the play so as not to leave us room for breath or movement. He’s planned every gesture, every step. He hated the opposition. He personally transferred the whole vision to the stage, rehearsing with the actors until they delivered the lines in a tone he heard in his own head. And that’s the Endgame in his adaptation. Like a tailor-made suit that perfectly fits the body. The acting is melodious, rhythmical. Beckett treated his plays like musical pieces. Thus, in his staging, Hamm and Clov rhythmically exchange lines of dialogue. Clov’s steps are even. There are no unnecessary gestures. The whole makes an incredible impression and keeps the viewer in a state of constant suspense. Hamm appears as a bitter, aggressive and hateful figure. Clov is like a victim that is unable to leave his tormentor.

Beckett was a master of dialogue and it’s simply impossible to spoil this text. But what can be done with it? What could Krystian Lupa have done with it? Contrary to what it might seem, limitations can lead you to new territories. By imposing certain limits on yourself you can obtain new qualities, searching for yourself within the self-imposed boundaries. And that’s precisely what happened with Lupa in Madrid. There’s not a single redundant word in his staging and all are in their proper places, yet what happens between them is surprising.

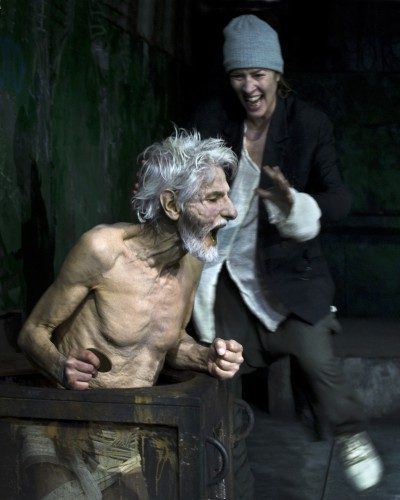

Endgame, dir. Krystian Lupa, Teatro de La Abadía. Photo: Ros Ribas

Instead of a curtain, the stage is surrounded by a phosphorescent painted line that glows red three times during the show. The Lupa-designed set came all the way from Valencia. It resembles a bunker, but don’t be deceived by appearances, for under the ceiling hangs a beautiful chandelier with prisms that, nevertheless, don’t decompose light, since no sunlight ever enters here. Beckett dissociated himself from the interpretation that the play was about the experience of war. And such is the picture we receive from Lupa. Everything is so contrastive – a chandelier in a bunker, Clov as a woman in trendy clothes and sneakers, Nagg and Nell in sarcophagi sliding out from the wall – that it actually becomes unbelievable. It is thus irrelevant whether this is France or Spain, nor whether this is the 21st century or shortly after WWII and we are looking at the ashes. These slight contradictions elevate the play above time.

In Beckett’s own stagings, the actors move like puppets, with him as the puppet master. He felt closer to Edward Craig’s theory and his über-marionette than to Stanisławski. According to Craig, the actor should abandon himself, his egoism, and use his body and voice as tools to no longer imitate but to indicate.

Lupa also dissociates himself from Stanisławski and Grotowski, but he feels a closer affinity with them than Beckett. The Irish director’s own stagings are thought out from beginning to end. Lupa’s plays arise from deep emotions, experiences, feelings. The actor isn’t just a puppet in his hands but a separate being that carries his or her own story. Lupa takes advantage of this. The actor gradually discovers the character in themselves. Everyone on stage acts naturally; even more: they behave as if the situation they’ve found themselves in were completely natural. And we believe them. Nell (Lola Cordón), half-naked, with her legs bandaged, sitting in a sarcophagus, from time to time rearranges the white scarf on her neck, examines herself in the mirror, or sips mineral water from a plastic bottle. She behaves like a true lady. They exchange pieces of dialogue with Nagg (Ramón Pons) in a somewhat clown-like fashion. Their faces or certain gags, like when Clov (Susi Sánchez) teases Nagg, as he reaches out for a cookie and she pulls it back, sticking out her tongue, bring to mind Peter Brook’s Beckett. But in Lupa’s version, there is something else, something that makes it impossible to equal the two visions.

Watching the Polish director’s staging of Endgame, we can’t help but think of Simone Weil. Hamm (José Luis Gómez) is like Job. He suffers and we sympathize with him. References to Christ on the cross, delicately alluded to in the original play, are in the foreground in Lupa’s adaptation. Simone Weil wrote of affliction which is “something apart, specific, and irreducible. It is quite a different thing from simple suffering…. Affliction is an uprooting from life, a more or less attenuated equivalent of death.” According to Weil, Job is but a figure of Christ. Is this true for Hamm, too? Not necessarily.

Samuel Beckett, Endgame, dir.Krystian Lupa, Teatro de La Abadía in Madrid.

Job accepts his affliction as a gift, reconciles himself with it. He sees that it stems from infinite love. Hamm doesn’t see it because affliction “makes God appear to be absent for a while…. During this absence there is nothing to love,” writes Weil. Hamm believes that his suffering is greater than anyone else’s. He is unable to feel compassion. He feels he is being encompassed by a void that can only be filled with words. It’s not death that makes him anxious, but life. Life, that perhaps doesn’t make sense and which causes you to suffer. There are moments when José Luis Gómez speaks in a shrill, tearful tone. We don’t really know whether we can trust him. Although he is blind, he looks at his own shadow on the wall or follows Clov with his “gaze” (which resembles the married couple in Bergman’s Hour of the Wolf where he humiliates her and yet she is unable to leave him).

Endgame, dir. Krystian Lupa, Teatro de La Abadía. Photo: Ros Ribas

Even if all this is just a game, suffering is undeniable. Suffering can’t be concealed and it has a human face. The picture emerging before our eyes reminds us of another one. That hanging a few blocks away from La Abadía Theatre, at the Prado, with Christ suffering and Simon helping him to carry the cross. Christ is looking in our direction, and there is an inexpressive pain in his eyes. “It would have needed another Christ to have pity on Christ in affliction” (Weil). We are unable to shoulder somebody else’s suffering. We stand helpless before them and the only thing left for us is to accept the inevitable. Nagg and Nell, who laugh at their own weaknesses, succeed in this to an extent. “For affliction is ridiculous” – Simone Weil’s words sound familiar. An almost identical line is uttered by Nell: “Nothing is funnier than unhappiness.” So we laugh too when Clov deceives Hamm or when Nagg tells the story of a tailor who made trousers much better than the world created by God. For the world forces us to live. “Do you not think this has gone on long enough?” Hamm asks sadly.

It’s actually unusual that a play that drags on can be so fascinating. Even the silence that falls over the stage several times is full of tension. We are part of this sad game that Clov pulls us into at the very beginning by saying paradoxically that it’s the end (and there’s virtually no reason for us to sit here). Clov attracts our attention with her gaze several more times. And at the very end, Hamm will throw away his dark glasses and scarf to stand up and walk up towards us, as if he were looking for help. His blindness becomes a metaphor for a crippled heart, unable to love or be compassionate.

Endgame, dir. Krystian Lupa, Teatro de La Abadía. Photo: Ros Ribas

Characteristically for Lupa, objects and music play an important role here. There are windows that Clov opens and closes, letting in the swoosh of the sea and showing a blue sky for a moment, which causes Clov’s voice to turn nostalgic. There’s an alarm clock that rings to remind us about time which, it would seem, has frozen still. And this can be felt literally in Lupa’s adaptation: time becomes a place. There is also a dog missing one leg and missing the ribbon. Holding it, Hamm for a moment becomes an innocent child again. Objects reveal emotions rooted deeply within us, often primal ones, the first emotions we may have experienced in our life. It’s a kind of collective sphere. During this brief moment, every one of us feels what Hamm may be feeling. An immense need for love, a feeling of unsatisfied love. Lupa shows us how we communicate this lack of love to each other.

This post was originally featured on Biweekly.pl in June 2010 and has been reposted with permission.

Translated by Marcin Wawrzyńczak.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Alicja Rosé.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.