Theatres remain closed, so instead of publishing reviews of new pieces, Etcetera asked artists to share a virtual contribution: a peek inside their studio, an insight in their research, or work in progress.

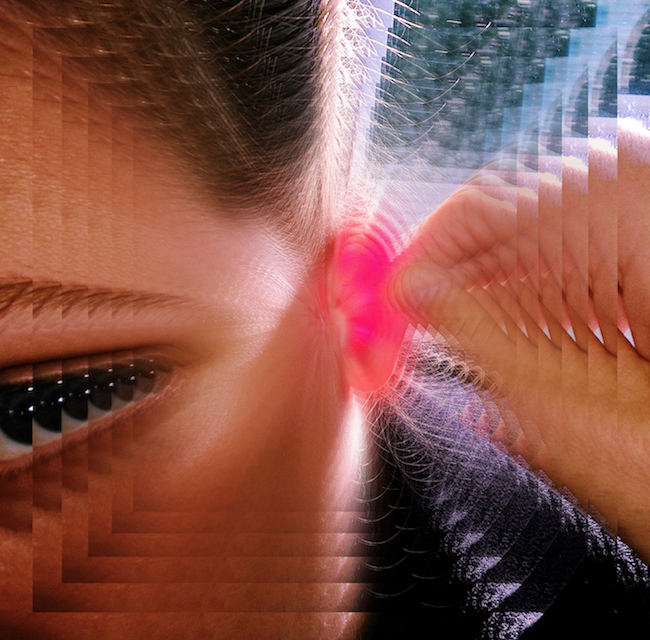

Why does it give me such a kick to hear a small detail that makes something swing? I’ll try to explain. It’s the musical, sensuous, groovy reward that comes with the practice of focusing attention. It’s the gratifying suspense of preparing the ground for a break. It’s the surprise of an unexpected gesture. It’s not always pretty, quite the contrary sometimes. Being in that place of the detail is always risky for a performer, there is a vulnerability that can produce an irregularity, a knot, a failure. But the moment of detailed failure can be an invitation for both listener and performer to come to terms with the fact that there is always another way. When you listen close, you can hear the alternatives. It’s in the moment of the detail that the olé or the yeah is mumbled and the heartbeat starts to sync up.

Listening in detail, is that where performer and audience meet? Where our attention converges? In the delight of the small, in the thing between the blanks, in the breaking of the break. And is it perhaps also a place for politics? Where social interactions are built and rebuilt. Where the way we listen together is sculpted, where we no longer take each other for granted. Where we stay with each other, in detail. Where we stop generalizing each other and we start noticing.

The reason I recorded this quickly improvised sound piece in my closet was because I was rereading the chapter ‘Entanglement and Virtuosity’ in Fred Moten´s book Black and Blur. He mentions Alexandra T. Vazquez’s book Listening in Detail: Performances of Cuban Music. I underlined Listening in Detail and it kept repeating in my head like a mantra, I locked myself in the closet, trying to shut out the sound of my son playing with Lego, and made the recording. It’s nothing much, it’s a miniature, a moment.

Something else that has been resonating with me for about two years now, from the same chapter of Moten’s book, is the story about saxophone player Kamasi Washington and his collaboration with Snoop Dogg. In an anecdote Washington explains that Snoop taught him to listen in a new way, to hear the “little subtleties”. He says “It wasn’t like the compositional elements in Stravinsky. It wasn’t about counterpoint or thick harmonies. It was more about the relationships and the timing, the one little cool thing you could play in that little space. It might just be one little thing in a four-minute song, but it was the perfect thing you could play in it. I started to hear music in a different way, and it changed the way I played jazz”. Hip hop is described as a “miniaturist art of deceptive simplicity”. It’s the art of detail and groove with its bare kick, its spacious rimshot, and the rapper weaving his verse around a deceptively simple warp.

This “miniaturist art of deceptive simplicity” has inspired me for many of my works (Nadita, Deep Etude, and Entangled Phrases to mention just a few). But I have to point out that it’s more hip hop than minimal music which is my source of inspiration when it comes to how I think of repetition and sequencing. The one doesn’t necessarily exclude the other, but sometimes I feel that my work is read primarily through a tradition of minimal composition.

The difference for me is that it’s not formal repetition that I am interested in; the repetition of a pattern, for the sake of perceiving change; the kind of composition that lays bare the listeners subjectivity and her sensing herself sensing. It’s something more than that; it’s that plus the resistance of the performer to become form; executor of the pattern. I´m interested in creating forms and patterns through a listening that includes failures, ruptures, and knots; that takes into account that even though there is a pattern, there is also always an alternative to that pattern, and it can come to life through listening in detail. And that’s when a pattern becomes a groove.

This article first appeared in e-tcetera on May 5, 2020, and has been reposted with permission. For the original article click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Alma Söderberg.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.