“Stop now! See that? You see that cloud? That beautiful shape?”

That is what Ken Reynolds would say to his daughter Adele when they went for walks in the countryside in her youth.

“He was always teaching me to see things,” said Erin Leach, Ken’s granddaughter.

I don’t know if Ken had already taken up photography at that point or not. I don’t know exactly when these walks might have taken place. But thanks to the story narrated to me by Erin, we know that the photographer in Ken was there all along. It was a matter of finding the right things to focus on.

Ken searched for some time. In what he called his artistic statement, written in 2009, he tells of traveling throughout Europe as a young man, seeing shapes, colors, lack of color, and patterns everywhere. His first exhibit would take place in Edinburgh in 1981. Over the next decade sixteen more followed throughout the UK, Estonia, Iceland, Finland, Hungary, Poland, Germany, and the Czech Republic. An exhibit of fifty photos, Secret Landscapes, traveled to numerous countries. Ten of these photos—beautiful, extreme closeups of rust patterns—were collected and published in a booklet, Secret Landscapes, in 1992.

For that booklet, Jonathon Brown wrote, “Ken Reynolds is an alchemist of imagery, using fine film and giving that unblemished sheen only photography offers. These gleaming flat pictures of flattish metal sheets in a variety of states of decay, corrosion, corruption and collapse, render a feast of analogy to our deepest ability to sense a hidden narrative of shape, colour and pattern in things.”

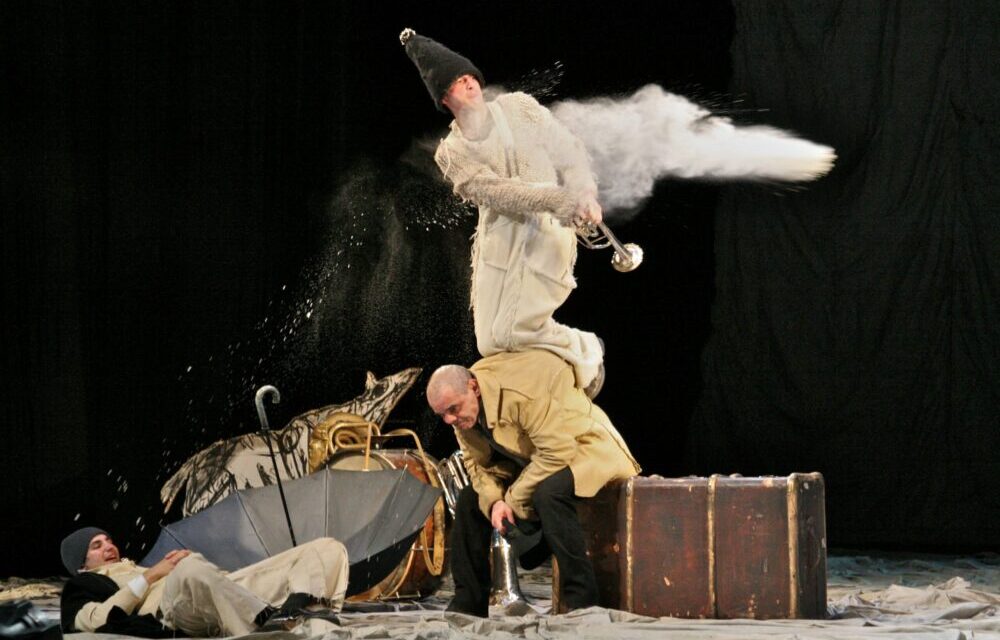

But then came Ken’s fateful meeting with Russian and East European theatre. That was the moment when an artist met his true inspiration. “Once started on this project it would not let me go. I searched out performances coming from Russia and the Ukraine in the West which I could catch without taking more than a day or two’s holiday. Then in November 1995 I went to Moscow for the first time…”

Lev Dodin’s production of Platonov for the Maly Drama Theatre of Saint Petersburg, 1997. Photo by Ken Reynolds.

When Ken Reynolds died at the age of eighty-three on Sunday, August 29, 2021, he had amassed a staggering archive of work, perhaps a half-million photographs of mostly East European theatre productions taken in over twenty countries. For most of his adult life, until he retired in 2003, Ken worked as an office manager in a law office, but he was an artist in every other waking moment.

Ken’s interests were broad, but he was a completist and a perfectionist. When he fell in love with a director’s work, he followed them wherever they went. Our correspondence was full of information about far-flung destinations: “I’m heading off to Romania”; “I’ll soon be in Iran”; “I’ve been catching up on Dodin in Milan and Vienna.” Some shows he shot five or six times, revealing nuances in the work that virtually no one but the director would ever see—he captured for posterity how these performances changed over time, whether that be from night to night, or decade to decade, and how they fit into ever new spaces as they toured to different countries and continents.

Ken told the story many times, but the most succinct version was in an email he sent me in 2014: “All the work I have done on Russian theatre was born the day I saw Gaudeamus in Glasgow in 1992. It literally changed my life.”

From another source: “By Ken’s own admission, as he watched [Lev Dodin’s Gaudeamus] he began ‘seeing image after image as a black-and-white picture.’ When Mikhail Tumanishvili brought his production of Midsummer Night’s Dream to Edinburgh in 1993, Ken brought along his camera and a love affair was consummated.”

So, 1992/93 is the turning point, the birth year of one who was to emerge as the finest, boldest, and most subtle theatre photographer I encountered in my thirty-plus years of writing about theatre. That casts no aspersions on the many tremendous photographers I have known and worked with. But no one had Ken’s well-tuned eye for theatrical detail. No one prepared like Ken. No one captured space, light, shade, and textures like Ken. No one played with emptiness in a frame like Ken—he loved to “push” objects or characters to the limits of the frame and leave the space between them vacant. Few could pack a frame with whirling action better than Ken. No one was as demanding as Ken, of himself or of the artists he photographed.

I saw Ken leave theatres without having taken a single photo. It might be because of a less-than-sensitive administrator (“They put me in the second row. I told them, ‘I must have front row center. I have no access to the work with someone sitting in front of me.’”). It might be because the work did not speak to him. I once recommended a show staged by a very fashionable and respected director in Moscow, but Ken sat glumly through the first act then announced at intermission that he was going back to his hotel. “I didn’t see anything to photograph,” he told me apologetically.

For all of the above, Ken did something with seeming ease and clarity that I have never seen in any other photographer: he had a way of capturing in a frame, or, at least, a few frames, the essence of a director’s work, the director’s intent and personality. I’ll put it another way: Ken created his own visual works of art based on the director and performers he photographed. His photographs were not mere visual reports of a theatre performance; they were full-fledged, independent artistic images. They revealed secrets even to the directors and actors whose work they portrayed.

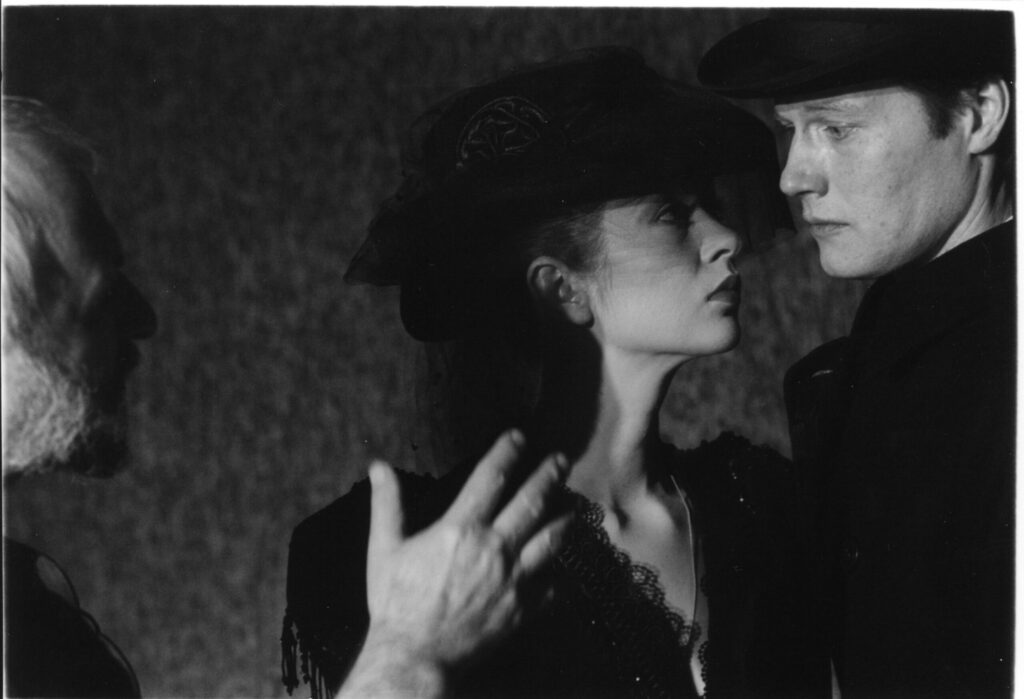

Scene from Henrietta Yanovskaya’s production of Witness for the Prosecution, Moscow Young Spectator Theatre, 2001. Photo by Ken Reynolds.

Robert Sturua responded to my note about Ken’s death with a heartfelt confession: “How imperceptibly, without words, quietly and mysteriously, he changed me. He made me better…,” Sturua wrote to me on Messenger.

Ken’s photographs of Yury Butusov’s work, one of his late loves, are dynamic, action-packed, and eccentric, just as Butusov’s productions are. His photographs of Kama Ginkas’s work are bold, aggressive, and exacting, divinely inspired by Kama’s own directorial vision. His photographs of Sturua’s work with Georgian and Russian theatres are epic in scope and filled with bits of tart humor, just as a Sturua production would be. His photos of Eimuntas Nekrosius’s work were filled with churning motion, a sense of anguish, broad strokes of action, and the geometry of stage design.

It is no coincidence that, with the rare exception of some benighted soul, directors were enthusiastic to hear that Ken had come to town and wanted to photograph their work. Ken would call me before coming to Moscow and give me his dates. I would run a check on what was playing and what was being rehearsed. Ken would then fill his schedule with day shoots at rehearsals, and evening shoots at performances.

Ken hated to waste time that could be used photographing actors at work. He flew in 2005 to New York to shoot a series of Kama Ginkas’s Dostoevsky adaptation K.I. from “Crime” on Off-Broadway at the Foundry Theatre. Taking a cab directly from JFK Airport to the venue on Forty-Second Street, he arrived literally moments before curtain up. Halfway into the piece, Ken slumped over, and his head came to rest on a piece of set decoration, a table in front of him.

My wife, Oksana Mysina, who performed (and still performs) Katerina Ivanovna (K.I.) in that show (such is my disclosure of potential conflict of interest), remained in character and walked over to Ken to check on him. He was unresponsive. Oksana feared he was dead or dying. With the help of the writer/actor Fred Kimball, who happened to be at that show and recognized immediately what was happening, Oksana was able to half-carry Ken backstage, all the while cracking in-character jokes to keep the audience in the dark about what was really going on. She finished the performance fighting off dread thoughts about what would greet her when she went backstage after the show ended.

However, instead of finding policemen, doctors, and nurses huddled over an expiring patient, Oksana walked in on Kama and Ken sharing a bottle of cognac and laughing to their hearts’ content. It had just been a case of jet lag hitting Ken at the wrong time.

Oksana Mysina in Kama Ginkas’s K.I. from Crime in New York, 2005. Photo by Ken Reynolds.

I first met Ken in Moscow in 1995. Someone had given him my phone number, and he called to ask if I would meet him. He needed some advice and guidance. I set up a rendezvous in front of the Theatre Library on Bolshaya Dmitrovka Street, just off of Pushkin Square.

For starters, we stepped into the entrance foyer out of the weather and Ken began telling me what he was interested in. I tossed off names and titles, all of which interested Ken. He was voracious that way. He talked about what brought him to Moscow (Dodin’s Gaudeamus and Tumanishvili’s Midsummer Night’s Dream in the UK), and I told him what might keep him in Moscow longer than he expected (Ginkas, Fomenko, Valery Fokin, Konstantin Raikin, etc.). The double doors leading into the library kept slamming back and forth as people came and went, pushing themselves past us as we turned and twisted to let them by. Ken was full of stories I wanted to hear, and I, apparently, had enough information to set his imagination afire. We stood in that tiny foyer talking for two or three hours. It never occurred to us to move to a more comfortable place. We were both happy right there.

When I posted the news of Ken’s death on Facebook, many mutual acquaintances shared their memories. “Otherworldly!” “One of the most modest but highly professional people I’ve met!” “A pure soul and divine talent!” “Always smiling!” Some mentioned his unchanging uniform of rumpled beige slacks, wrinkled shirt, and a loose-fitting photographer’s vest hanging from his shoulders. The collective portrait to which each of these comments contributes is precise and true. It wasn’t so much that it looked like Ken slept in his clothes, you were just pretty sure that he didn’t want to waste time dressing and undressing when he could simply fall into bed after an evening shoot and roll back out ready to be at someone’s 11 a.m. rehearsal.

As for his famous sweet, gentle nature, Kama Ginkas put it most succinctly. “Ken was an angel,” Kama said when Oksana called to tell him Ken had died.

Ken himself adored his favorite directors. When Ken and I once were together at a festival in Wrocław, Poland, I recorded several conversations with him for YouTube and for posterity. They are well worth watching. Ken’s careful way of speaking, his simple though brilliant insights into his and others’ art, and his affection for the artists that inspired him are a genuine treat.

On Eimuntas Nekrosius: “One should understand that, with Nekrosius, so many things from the stage have several meanings, and one is always in for a surprise.”

On Lev Dodin’s Gaudeamus: “It starts. And there are people coming out through the snow, going into the snow, and disappearing, and here is theatre unlike anything I’ve seen before. And I suddenly realized I was thinking photographs, black-and-white photographs. I’d never photographed the theatre in my life. But this was impelling. And I was determined that something must be done with this.”

On photographing the works of Anton Chekhov: “Chekhov. A photographer’s nightmare or a photographer’s delight? One of the great problems with Chekhov is that these are plays of alienation, and many directors use their large theatres to reveal this with a wide, wide open space. And, so, you have one character on the left, front, and one character on the right, back talking to each other with a great gap in the middle. And one thinks this is going to be a very negative picture. But, the more you listen and watch, when it’s a great production, you suddenly realize, this is what it’s supposed to be.”

On Kama Ginkas: “Every now and then, not very often, there is a moment that changes one’s life. One of these occurred in 1995 when, for the first time, I was in the Theatre of the Young Spectator in Moscow, and met in the White Room Kama Ginkas. We talked about K.I. from ‘Crime,’ and I began to realize that here was a man totally committed and meticulous in every detail.”

In these conversations and elsewhere, Ken drops hints about the long and winding road he traveled before becoming a theatre photographer. In a video where he talks about Robert Sturua, he mentions seeing Sturua’s Richard III in Edinburgh ten or fifteen years before he would begin photographing. In an email to me, he revealed just how influential the Edinburgh festival had been on him, and how early that influence was manifested.

“I’m pretty certain that the name Richard Demarco might be familiar to you,” Ken wrote to me in 2014. “I have known him since the early 1970’s when he was introducing the work of Tadeusz Kantor and Josef Beuys to Edinburgh audiences. He has been [an] intrepid explorer of Eastern European theatre and culture.”

Kama Ginkas (left) rehearsing The Lady with the Lapdog at Moscow Young Spectator Theatre with Yulia Svezhakova and Igor Gordin, 2001. Photo by Ken Reynolds.

Thus we have Ken Reynolds, at the age of approximately thirty-five, already encountering East European theatre, finding it to be of interest, and remembering it. It would take twenty more years before he would enter a theatre with a camera in hand. Fortunately, there would be another twenty-five-plus years in which Ken Reynolds would work his photographic magic.

But then came that fateful meeting with Lev Dodin and the Maly Drama Theatre of Saint Petersburg, and he began photographing theatre. His work appeared in newspapers, magazines, and books in the UK, the United States, Russia, and Europe. His theatre photos were collected for numerous exhibits in the United States, the UK, Finland, and Russia beginning around 1995.

Ken was always extremely generous with his work. At his own expense he would cull and print 150 to 200 photos of each show he photographed, and present the bulky packet as a gift to the director. As such, most of the theatres and directors that he followed closely possess high-quality, mini archives of Ken’s images.

Starting around 2013, Ken’s gifts became even more extravagant. He self-published high-quality, glossy, oversize books and presented them, free of charge, to his favorite directors. These books were also available for individual purchase online, so there are multiple copies of some of them out in the world. Some, however, exist only in two copies, one for Ken, another for the director. Talk about collector’s items. Ken made multiple books for Dodin, Ginkas, Genrietta Yanovskaya, Boris Yukhananov, and Yury Butusov.

After Ken suffered a mild stroke in January 2018, his coverage of the great theatre of his time came to an end. He allowed that trips to Moscow would now be too difficult, but he hoped he might take shorter trips to Oslo, Poland, Germany, or France to catch touring companies. To my knowledge, no such trips ever took place.

On the occasion of Ken’s eightieth birthday, Kama Ginkas and Genrietta Yanovskaya asked me to translate and send a greeting that they had prepared. The heart of it is worthy of quotation:

“Dear Ken… Your photos are wonderful, artistic documents of theatre. You have an incredible sense of things. Amazingly, you always know what part of the world and which country to go to (especially if it is Russia or the post-Soviet space). You have the ability to anticipate the theatres, even the smallest, where new art is being born or might be born. You immediately see what is unique and inherent to a specific director and specific performances. Theatre is an art that evaporates. To capture moods that shift every second, and to grasp an actor’s emotion that has just come into being is to stop and capture for posterity the moments of life and the moments of theatre. You are always up to that task. And that is why we love you…”

Ken Reynolds in a Moscow cafe in 2015. Photo by John Freedman.

As I have sifted through old documents and correspondence these last few days, I have relived many hours and stages of one of the deepest, richest, most rewarding friendships of my diverging and intersecting personal and professional lives. But Ken was so much more than a friend to everyone who knew him well. He became a part of your family. He was a full-fledged member of that loose, contentious family of people making theatre in Eastern Europe. His record of that theatre will make it more accessible, more fascinating, and much clearer than it would have been without him.

A few years ago I received one of those letters Ken would send when he was preparing a trip to meet up with his inspirations. This one catches my eye today because it captures a moment when that crucial Dodin production of Gaudeamus came full circle, and it gives Ken’s own evaluation of the life and work that followed that chance encounter way back when.

“…I am due to photograph in Paris Dodin’s revival of Gaudeamus with a new young cast,” Ken wrote. “The seeing [of] the original in Glasgow in 1992 was the one that left me determined at all costs to photograph theatre. What an incredible 23 years has followed!”

In fact, twenty-six incredible years followed. It was a quarter of a century of theatre captured as never before, by a true wizard of his art. Thank you, Ken. Farewell.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by John Freedman.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.