The atmosphere at the Imperial Bolshoi Kamenny Theater in St. Petersburg, Russia, must have been electric on Feb. 4, 1877. That was the day Austrian composer Ludwig Minkus premiered La Bayadere—the latest masterpiece of classical ballet by French choreographer Marius Petipa—to some of Europe’s cultural elite.

Fast-forward almost 140 years to another grand premiere of the production, this time in Niigata, where Jo Kanamori, artistic director for dance at the city’s Performing Arts Center, will stage La Bayadere—Nation Of Illusion, his revolutionary reworking focusing on modern themes.

The 41-year-old director and choreographer says Pepita’s original story deals with India’s caste system and the repercussions of betraying the one you love.

“In a similar way, this new program deals with a reprehensible fact of history that the Japanese were deeply involved in,” Kanamori explained, referring to a main thematic element in his La Bayadere that reflects some of the country’s wartime actions in the 1930s and ’40s.

The production’s aim is to keep the lessons of history in the public consciousness since by nature, such memories tend to fade with the passage of time.

“That point — how to present the past to a new generation—also relates to the essence of the performing arts, because live performances vanish from sight when they’re over,” he adds.

At a press conference in April, Kanamori announced he was working on La Bayadere with leading playwright and theater director Oriza Hirata, as well as three top actors and dancers from Kanamori’s Noism troupe.

“This all started two years ago when I briefly met Hirata at a regional theater,” Kanamori explained. “I asked him to write something for Noism. It was spur of the moment and intuitively it made sense to me, and to my surprise, he agreed.”

However, Hirata soon had to admit he was stumped when it came to writing an entirely new ballet, so he and Kanamori agreed to adapt a classic. They chose La Bayadere because it is staged less often.

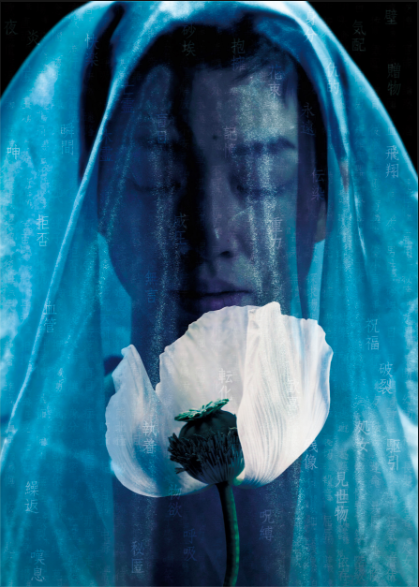

Looking back: The ghost of a murdered temple dancer (played by Sawako Iseki) reflects on life’s woes in La Bayadere — Nation of Illusion.

The original story, set in India, is a romantic tragedy between a woman and man from two different castes: a temple dancer named Nikiya and a warrior named Solor. Though the two are in love, a powerful rajah asks Solor to marry his daughter, Gamzatti. Meanwhile, a high-caste brahmin pressures Nikiya to become his concubine, but she rejects the idea. Nonetheless, Solor becomes enamored with Gamzatti’s wealth and beauty.

Nikiya is ordered to dance at the couple’s engagement party, but she dies after being bitten by a snake Gamzatti hid in the flowers she gave her. This breaks Solor’s heart, and to escape his guilt he starts smoking opium — only to meet Nikiya’s spirit in his drugged state. That hypnotic scene, known as “The Kingdom of the Shades,” is one of ballet’s most famous excerpts.

Solor and Gamzatti’s wedding ceremony becomes a scene of destruction after Nikiya’s spirit appears and the gods became angry, destroying the temple and the people in it.

Hirata was also present at the April press conference. In January, he directed an opera about the Fukushima nuclear disaster titled Umi, Shizukana Umi (Calm Sea) at the Staatsoper Hamburg in Germany.

“In Europe, public theaters usually try to create programs that relate to people’s lives and address deep social concerns. It’s seen as very important to tackle current social issues,” he said. “Unfortunately, there are only a few theaters in Japan that fulfill a public-interest role, so Kanamori and I decided to create a work that tries to get at the root of so many problems we have in our country’s society today.”

To pursue that aim, Hirata stuck roughly to the original La Bayadere story but transposed it to a supposedly fictional (but quite easily identifiable) country in Asia called Yanpao.

He also switched the production’s class and caste conflicts to reflect the rival interests of the Japanese, Koreans, Han Chinese, Mongolians, and White Russians in areas of northeast Asia occupied by Japanese forces from 1932 to 1945.

“When I saw different versions of La Bayadere, I got a strong image from the last scene, the final destruction of the temple, which overlaps with Japan’s wartime history,” Hirata said. “At that time, as Japanese, we deluded ourselves into founding a dream country even though it comprised five ethnic groups who were opposed to each other’s political, religious and cultural values — and finally it collapsed into ruin just like the temple in La Bayadere.”

In the moment: Sawako Iseki, Noism’s vice-artistic director, rehearses for La Bayadere — Nation of Illusion, by Jo Kanamori and Oriza Hirata. | © RYU ENDO

Kanamori has interpreted Hirata’s script in some notable ways. “Three actors deliver the words from Hirata’s text, but the dancers never speak,” he explained before adding that he asked Hirata to still write scripts for each of the dancers so that they would know exactly what they were supposed to convey through their movements, and so they’d be in line with the speaking performers’ intentions.

“The dancer’s silence is important because I want them to be characters who intentionally don’t speak in order to protect themselves politically or to protect their position — or simply because they are too weak to do so.

“As a result, when they react to the words of the actors, who are in superior positions to them, their movements reveal the essence of their oppression.”

Although Kanamori uses about 70 percent of Minkus’ original score, he also enlisted the help of composer Yasuhiro Kasamatsu to specifically add music using Asian instruments to conjure his imagined country. He also had longtime collaborator Tsuyoshi Tane, a Paris-based architect, design the stage sets, and he recruited abstract wood-artist Masaki Kondo to decorate them.

Adding to this roll-call of luminaries, Kanamori also brought in Yoshiyuki Miyamae, chief designer of the Issey Miyake fashion brand, to take charge of the costumes.

With regards to the ballet’s climactic scene of the temple’s destruction, Kanamori said that a key theme of his work is “illusion,” and that transiency closely relates to people’s memories and the very nature of history.

“Consequently, I didn’t want to show everything falling apart on stage, but I try to show the moment when something collapsed in the people’s inner world,” he said. “I want audiences to accept and pass on the memory of what happens when values collapse — and I hope they will regard today’s society through the lens of such recent history about the ruined, former nation of illusion.”

Emotional expression: Sawako Iseki, Noism’s vice-artistic director, rehearses her role as a temple dancer lamenting her doomed love for a flighty warrior (played by Satoshi Nakagawa) in La Bayadere — Nation of Illusion. | © RYU ENDO

It has been 71 years since the end of World War II, and, as time passes, it seems that the people in power appear all too keen to forget historical lessons. With the success of his Fukushima opera behind him, it would be refreshing to see Hirata and Kanamori’s La Bayadere bring about a new tide of political awareness in the country’s art — something that would make the stages of Japan as electrifying as the Bolshoi’s so many decades ago.

La Bayadere — Nation of Illusion runs from June 17-19 at the Ryutopia Theater at Niigata City Performing Arts Center in Niigata Prefecture (start times vary, tickets for adults cost ¥3,000-4,000 with discounts for those under 25). The production then moves to Kanagawa Arts Theatre (July 1-3), Hyogo Performing Arts Center (July 8 and 9), Aichi Prefectural Art Theater (July 16), Shizuoka Performing Arts Center (July 23 and 24), and Yonago Culture Hall (July 24). For more information, call 025-224-5521 or visit labayadere.noism.jp.

This post originally appeared on The Japan Times on June 16, 2016, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Nobuko Tanaka.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.