Failure is embedded in the British national psyche. Or rather, the ability to turn defeat into a myth of victory: think of Dunkirk, think of Eurovision, and, more to the point, think of soccer. Ever since the high point of 1966, when the England football team won the World Cup, against Germany, decades of dreaming has inspired both hope and resignation. Somehow the team has failed to win either the European or World trophies. Now, after Brexit and COVID, our national identity feels more bruised than ever so James Graham’s latest state-of-the-nation drama, which tells the story of England football manager Gareth Southgate (played by Joseph Fiennes) and his team, feels especially timely.

The story begins in personal agony: in the semi-final of the 1996 European Cup Southgate misses a penalty and England lose the match — against Germany. When, some 20 years later, he becomes the England manager, he decides to analyze what always goes wrong with the national team, and then to turn things around. The central psychological problem is two-fold: the team is not united, and they always lose on penalties. First he chooses a fresh young squad: captain Harry Kane, goalie Jordan Pickford, and players such as Harry Maguire, Deli Alli, Bukayo Saka, Marcus Rashford, and Raheem Sterling.

But Southgate’s main insight is that the team’s psychology is as important as their physical fitness. Despite skepticism from the old guard of trainers, who prize aggression over touchy-feely mental health, he hires psychologist Pippa Grange (Gina McKee) to talk to the players about their fears and feelings, and to bond by creating a deeper sense of mutual trust. The best scenes are those in which Southgate and Grange try to relieve the pressure of expectations on the team: admiral Nelson’s signal at the 1805 battle of Trafalgar —“England expects every man to do his duty” — weighs as heavily as the memory of the World Cup victory of 1966.

Southgate and Grange not only want to lower expectations, and confront the fears of the players (especially about the dreaded penalty shoot outs), but they also aspire to create a new story. Instead of inevitable defeat and disappointment, they want the players to think of themselves as part of a new narrative, a three-act drama: in fact, the story arc of Dear England, whose title comes from Southgate’s 2021 mid-pandemic letter to the nation, goes from the 2018 World Cup in Russia, the 2020 Euros (delayed to 2021 because of COVID) and the 2022 World Cup in Qatar. The most tense scenes are re-enactments of the penalty shoot outs in these competitions, some of which England won, and some of which they lost. As usual, I had to close my eyes at these almost unbearable moments.

The linking of Southgate and Grange’s psychological interventions, and the response of the players as they come around, with statements about the national psyche are unoriginal, but occasionally very moving. The continuity between recent England teams and those from some 150 years of football history are fascinating, as are the insights into the legendary 1966 team, and there is room in Graham’s typically sprawling epic for the symbolism of taking the knee to protest against racism in football, and also for the 2022 Euro victory of the England women’s team. But for all of Southgate’s achievements, and despite a thoroughly enjoyable production by Rupert Goold, the grim truth is that if the England team now lose less badly, they still haven’t won a trophy.

As usual, Graham includes a lot of surplus material which stretches the show to close to three hours. Appearances by Spitting-Image-style British politicians could have been dropped, and the glimpses of fans and Morris dancers celebrating are inessential. A bit of editing could remove some of the bagginess, and it must be said that this is a play which needs such resources, some 25 actors, that it’s hard to see it being revived by another theatre. On the other hand, the fun of the show is aided by the speed of the storytelling, music from The Verve and Stormzy, and the evening ends on a huge high as the manager and players, as well as the audience, belt out the sport’s anthemic “Sweet Caroline” — “So good, so good!”

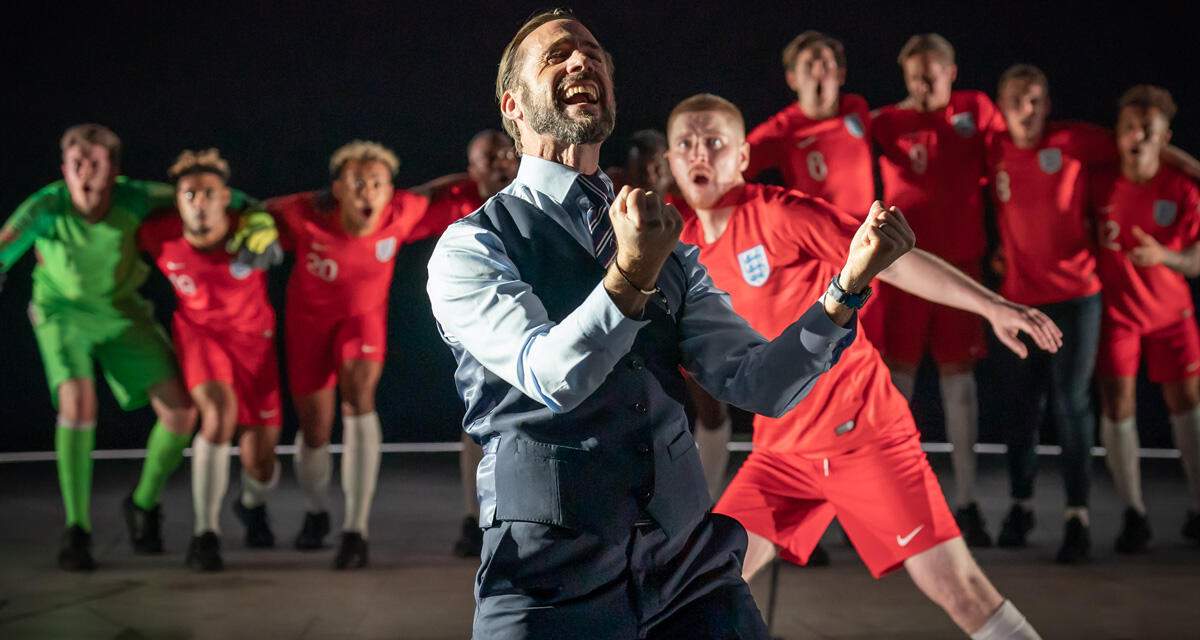

The cast is held together by Fiennes and McKee. He has an extraordinary ability to embody the decent “Gareth from Crawley”, showing both his strong sense of failure and his determination to learn from mistakes. He is ordinary, but sensitive to his individual players. It’s one of those performances that is so mesmerizingly convincing that you could swear that you are watching Southgate himself. Likewise, McKee articulates the earnestness and occasional awkwardness of the female psychologist in what is a man’s world, heavy with testosterone. I am less inspired by the representation of the players, which is often very close to cartoonish caricature: Will Close’s inarticulate Harry Kane, Darragh Hand’s sincere Marcus Rashford, Lewis Shepherd’s passionate Dele Alli, Adam Hugill’s thick-skinned Harry Maguire and Gunnar Cauthery’s smooth Gary Linekar.

On the other hand, like the squad itself, this is clearly a team effort. Across the expansive Olivier stage, circled from above by designer Es Devlin illuminated halo, a symbolic Wembley Arch, the football matches are represented metaphorically rather than literally by Ellen Kane and Hans Langolf’s choreography. Yet for all the good natured jokes about the three lions, pre-match superstitions or Southgate’s waistcoats, Dear England is as disturbing as it is thrilling. Its populist finale gives a massive nationalistic uplift at a time of dismal social and economic decline. Exalting in the past moments when “good times never seemed so good” sounds queasy in a country where nothing works, where increasing numbers of people are impoverished and where the political class is mired in failure. It’s more than football that needs fixing.

- Dear England is at the National Theatre until 11 August.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.