All the rage in Beijing’s stand-up circuit, Pazilye Parhat says much of comedy stems from genuine anger she’s experienced all her life.

A little after 8 p.m. on the eve of the Mid-Autumn Festival on September 20, Pazilye Parhat wove through the streets of Xidan in Beijing on a shared bicycle to her fourth stand-up comedy gig of the day.

It had just rained, and the road was full of bumps and potholes. “You wouldn’t expect the roads to be this bad,” says Pazilye, narrowly avoiding a puddle.

At the Star Theatre, the back door was open, and the sound of applause and laughter trickled from the front stage through a thin red curtain. The backstage was stark and empty, with no staff or dressing tables for hair and make-up.

The only person around was the MC — the previous comedian had left immediately after delivering their set, while the follow-up act was running late. He had just sent Pazilye a message pleading: “Please stall them for me. I got held up at my first set.”

A 29-year-old Uighur woman from Aksu in the northwestern Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, Pazilye majored in Russian at a university in Tianjin, approximately 100 kilometers southeast of Beijing. Since graduating, she’s worked multiple jobs in Beijing, but says, “Nothing worked out and I didn’t like anything I was doing.”

But ever since she joined the stand-up scene in November last year, she’s had more energy than ever before.

The Mid-Autumn Festival holiday is the busiest time for stand-up comedians, and Pazilye’s schedule is crammed with gigs. To make the most of her time, she’s booked two consecutive sets in Sanlitun: 4:30 and 5 p.m. The two venues are only a few hundred meters apart.

At 7:30 p.m., she has two more gigs in Xidan, at venues about one kilometer apart, before a fifth and final performance back in Sanlitun.

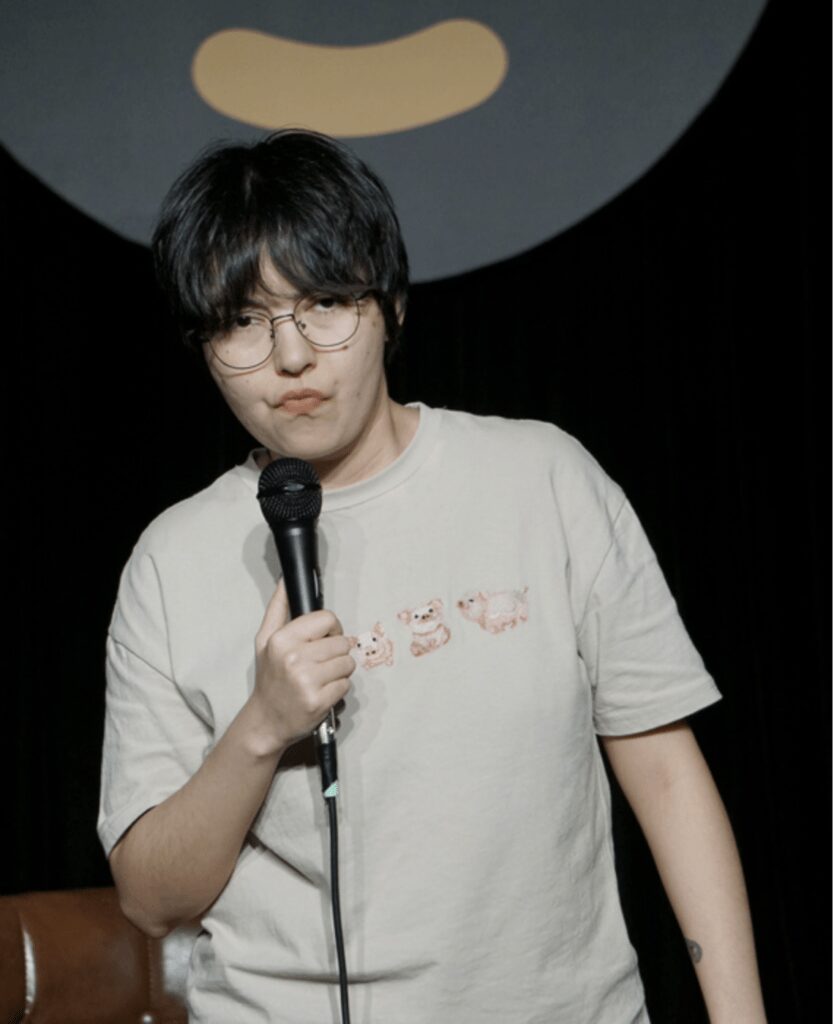

A photo of Pazilye from a performance in Beijing, 2021. Photo Credit: Pazilye’s Weibo.

Each show generally comprises four or five comedians, and the order and duration of their sets are quite flexible. Tickets cost around 80 to 200 yuan ($12 to $30).

On stage, Pazilye satirizes sexism at the workplace and talks about menstrual shame. She says her jokes stem from genuine anger she’s experienced all her life.

That’s stand-up comedy for her: she splays open her wounds for everyone to see, rubs in a little salt, sprinkles a little seasoning, and deconstructs them bit by bit. When the show is over, the pain isn’t so raw anymore.

Back on stage in Xidan, Pazilye delivered her big punchline and a wave of laughter rippled through the audience. Backstage, the host and the follow-up act who just arrived heaved a collective sigh of relief. Just a few minutes ago, both grumbled in tense whispers that not many people had come and that the atmosphere was a bit stiff.

After a set of a little more than 20 minutes, Pazilye walked off-stage amidst applause, took her bag, and left the venue. Her next set started in an hour, and was 10 kilometers away.

On exiting the closest subway station, she jogged the rest of the way to the venue, this time in Sanlitun, her messenger bag lightly slapping her shoulder with every step. Inside was all her luggage from a business trip — she’d just returned from a performance in Shenyang in the northeastern Liaoning province by high-speed rail and didn’t even have time to go home.

Over the past year, Pazilye has grown accustomed to this daily cycle: wait to go on stage, deliver her set, and rush to the next one. When she doesn’t have time for a proper meal, she buys a sandwich from a convenience store and wolfs it down as she jogs to her next gig.

She hardly ever takes taxis — to keep expenses down and fearing traffic jams. But then again, she’s also always loved exercise.

On September 20, to avoid showing up to the venue drenched in sweat, Pazilye specifically chose to wear a loose-fitting shirt and shorts, though the early autumn night was already a little chilly.

Pazilye takes a subway between shows, Sept. 20, 2021. She frequently books multiple performances in a single day, some of them kilometers apart. Photo Credit: Hou Xueqi for Sixth Tone.

Making Ends Meet

In the world of stand-up comedy Pazilye is a newcomer, but she’s also a determined hustler. Once, on her busiest day, she performed at eight venues across the city. “I have to feed myself,” she says calmly, with a lazy smile.

Her family doesn’t exactly know what she does in Beijing. She once told her father she sometimes works with Joe Wong, a comedian and TV host who appeared on The Late Show with David Letterman. He believed she worked for a TV station, which sounded like a decent job.

To make ends meet, Pazilye has carefully calculated that as an emerging stand-up comedian, she must perform at least 30 sets a month. Because she’s working her way up from the bottom, she has a “high performance-price ratio,” only earning a few hundred yuan per set.

Despite this, Pazilye is grateful she’s still at that point in her nascent stand-up career where she’s excited about performing. “I haven’t gotten sick of it yet — every performance is a reward,” she says. To make a living telling jokes, rushing from one set to another is an inevitable rite of passage.

This lifestyle was unimaginable seven or eight years ago.

“It used to be all part-time work — now, about half the stand-up comedians work full-time,” says Tian Long, founder of Beijing’s C+ Stand-Up Club. Over the years, he’s witnessed the industry bloom from nothing and has helped kickstart more than a few careers in stand-up.

Eight years ago, live stand-up was still uncharted territory in Beijing — there were only a dozen or so stand-up comedians in the entire city, and none worked full-time. Moreover, they simply performed because they enjoyed it, and the audience merely had to buy a drink to see the show.

In those early days, comedians did take on the occasional paid gig, but in front of thin crowds, where tickets cost around 50 to 80 yuan. The profits from each show generally only paid for all the comedians to eat a barbecue together.

But today, things are different. Tian Long recalls that in Beijing, the pivotal period in the industry’s transformation was in 2017 and 2018. Then, TV shows such as Roast! and Rock & Roast became hits overnight, drawing public attention to the stand-up show industry.

Tian Long performs in Beijing. Photo Credit: Courtesy of Tian Long.

As audiences grew, so did the capital that investors were willing to front for such shows, thus paving the way for aspiring stand-up comedians. Since then, professionals and amateurs have stepped up to the plate.

In 2019, new shows popped up everywhere. “Seemingly overnight, everyone in Beijing suddenly claimed to own a production company. At that stage, the market was more chaotic — many companies that opened in April disappeared by June. That said, the shows introduced us to a lot of budding comedy talent. They eventually became the first wave of comedians to run the stand-up circuit,” says Tian.

“Now, a full-time comedian can perform a 15-minute set for six months and easily make 8,000-10,000 yuan a month. If you’ve been around long enough, you may get even more lucrative opportunities.”

According to Tian, though working the comedy circuit is grueling work, performers choose their own schedule and many are excited about this life. “At the end of the day, it’s more interesting than working a regular office job,” he says.

Pazilye’s reasons are simple: “Because it makes me happy.”

Lang Qi, a fellow performer who stood next to her as he waited to go on stage, nodded fervently and laughed: “Yes, it’s so much fun. And, as you can see, I’m not going to starve to death — I’ve even put on some weight,” he says.

Lang, a former start-up owner, began performing stand-up as a hobby in 2019 but stopped temporarily due to a sudden illness. His recovery gave him the inspiration to follow his true passion. He shut down his company and pursued stand-up comedy full-time.

Pazilye fits in a meal backstage in Beijing, Sept. 20, 2021. Photo Credit: Hou Xueqi for Sixth Tone.

Working the Circuit

Pazilye’s first stage performance was in August 2020, at an open mic event in a bar called The Mushroom Shop.

Her set comprised mainly anecdotes about her experiences with fibrocystic breast changes, which satirized the inequality between men and women. She recalls feeling nervous: her hands shook and she couldn’t control the rhythm or power of her speech. At times, she was worried about coming across as “too intense.”

But it went well, with more experienced comedians praising her potential. Going on stage gave Pazilye unprecedented confidence — a stark contrast with the last 28 years of her life.

Until the age of 18, Pazilye says she lived a trapped life, and was continually troubled by the feeling that she lacked agency. Her parents divorced and she was raised by her grandparents.

She felt like she had the gift of humor, which she supposed she inherited from her father — though his sense of humor when talking to other people was rarely apparent in his conversations with her.

“I loved my dad, but he didn’t love me. He would’ve preferred to have a boy. That took me many years to accept,” says Pazilye.

Growing up, she was constantly taught to be submissive. “As a woman, my role was to be an accessory to men.” She never received praise in school as a child and always felt like nothing she did was right.

At the time, hypersensitivity and a strong inferiority complex took root to the point that when she walked outside, she hugged the walls to stay inconspicuous and always crossed her arms, fearing people would judge her for how hairy they were.

All that changed in Pazilye’s second year of university when she stumbled on a few clips of foreign stand-up comedy online. She was immediately hooked. “Every day, I stayed holed up in my dormitory and even skipped class to watch stand-up. I must have seen a few thousand hours of it,” she says.

She likes the caustic humor of women like Asian-American comedian Ali Wong and TV show 2 Broke Girls co-creator Whitney Cummings. Their bravery moved her, she says.

Occasionally, Pazilye jots down some of the more amusing events from her life as potential anecdotes: some she saves on her phone, while others she shares on social media or tells her friends.

But for years, stand-up comedy was just a pipe dream. And the initial, sudden craze for stand-up variety in China didn’t even attract her attention.

Until Christmas 2019. Then, she caught a live comedy show in Beijing for the first time, and more importantly, discovered there were stage opportunities for aspiring comedians in China too.

After the show, she gathered the courage to find Tian Long and tell him she was a stand-up fan and wanted to try her hand. He readily accepted, saying, “No problem. Come have fun with us after the New Year.”

However, the COVID-19 outbreak ground live performances to a halt, and it was more than six months later when Pazilye finally made it on stage.

Pazilye (second from left) performs on stage at a club in Beijing, 2021. Photo Credit: Weibo.

At that time, Pazilye worked an internet commerce job in which she had no interest. “I had no sense of gratification or value — I just did it to pay rent and eat,” she says. She consistently struggled at the workplace, too; over just two years, she changed seven jobs and experienced sexual harassment.

In November 2020, when Pazilye suddenly lost her job, stand-up comedy unexpectedly came to the rescue. It provided her that little extra money to supplement her savings. Soon, she began performing full-time.

But before long, another COVID-19 outbreak during the 2021 Spring Festival pulled the rug out from under her feet. Live shows ceased again, with only one stand-up comedy club in a desolate area to the north remaining open in Beijing. The club’s owner gave Pazilye the chance to perform five sets a day for a week, pulling her back from the brink of despair.

Since then, Pazilye has taken to various stages — theaters, bars, cinemas, and even conference rooms, shopping mall VIP areas, and barbecue restaurants. On one occasion, she was invited to perform at an even more unlikely venue: the sub-district community affairs service center.

“I’m probably the most booked female stand-up in Beijing,” says Pazilye of her experiences working the circuit. Pausing for a moment, she corrected herself, saying, “Scratch ‘female.’”

She says stand-up has given her new experiences and realizations. She’s surprised that so many people are willing to listen to her, and that her material needs to be submitted beforehand for scrutiny from various levels of management.

The constant performances have also allowed Pazilye to make rapid progress, and she says she’s received more and more invitations for TV and variety show jobs.

The laughter and applause from the audience give her a sense of security. She feels “free and powerful.”

“I stand on stage facing dozens or hundreds of people. Many in the audience are more successful and earn way more than me, but people still pay to hear what I have to say. I can anticipate what’s going to make them laugh before I even speak,” she says. “When I lead them down my path of reflection, I feel incredible — powerful, even.”

Stand-up has given her satisfaction and helped her confront her insecurities and inferiority complex. On a post on the microblogging platform Weibo titled “To My Audience”, she wrote: “You can’t imagine how validating it is for me when you take a photo with me or simply give me a compliment when my set is over. It means the world to me, way more than you could’ve imagined.”

Photos of Pazilye from 2020. Although she used to be a model, she says that audiences respond better to her jokes when she doesn’t pay attention to her appearance. Photo Credit: Weibo.

The Other

On September 20, Pazilye delivered five sets, and she was the only woman on stage at each gig. But she didn’t stick out all that much among her entirely male cohort.

That day, she had a few pimples on her face, hadn’t put on make-up, and her short hair was somewhat greasy. Her overall appearance was very plain, almost androgynous.

Pazilye was once a part-time model and still enjoys wearing make-up, but on stage, she deliberately plays her beauty down. “I have tried it more than once, but the audience doesn’t laugh if I’m too pretty or girly. It’s weird. But when I don’t wear make-up and look like a slob — without washing my face and wearing hoodies or baggy clothes — they go wild.”

Curling her lips, she says, “Perhaps when my sexual characteristics are hidden, the audience focuses more on my jokes.”

Had she not planned any sets that day, she would have been a lot more dressed up. A few days before the performance, she went out to take a drum lesson and watch a movie. For that occasion, she had on thick eyeliner and bold, red lipstick; she wore hot pants and a hairband, as well as four rings on her fingers.

Walking along the crowded Xidan Street, she attracted stares as well as a few unsolicited advances from men, and women. They asked her: “Can we be friends? Can I get to know you?”

Since becoming a stand-up comedian, the anxiety Pazilye once felt about her appearance has completely disappeared. She says she’s started to like herself, accept who she is, and has become more and more confident. “Now, I dare to go out without shaving my legs. Before, that would have been impossible.”

Performing has also interfered with Pazilye’s once structured routine. Staying up late and eating poorly has caused drastic changes — she’s gained weight, her throat and back hurt, and she’s even begun to lose hair.

Once, a club owner sent a message asking if she had gotten fat, and told her to put more effort into her appearance. Pazilye shot back: “Does this requirement also apply to male comedians?”

She hates being treated differently. But, she says, “Unfortunately, women are often thought of as ‘others.’ For instance, there’s a part of my set where I say I can’t sleep, my boss has sat up in bed next to me. Everyone laughs when they hear the word ‘boss.’ They assume the boss must be a man.”

Compared with TV or online broadcasts, the most important characteristic of live comedy is the degree of interactivity.

Pazilye has a knack for engaging crowds and can sometimes be a little offensive. During her sets, her expression is at times exaggerated, even theatrical. When she’s backstage listening to other acts telling a funny anecdote, she doesn’t muffle her laughter, occasionally even slapping her thigh and cackling loudly.

But when she talks about menstrual shame on stage, she suddenly gets serious. “I want to tell all women out there that there is no need to be ashamed about your body and your needs.”

Back in Sanlitun, at the end of Pazilye’s fifth and final set on September 20, a young woman approached her to say, “I really like the way you express yourself. Keep up the good work — I’ll come see you again next time.”

This is what moves Pazilye most. She says that since she started stand-up, many in the audience — especially young women — come up to talk and take photos with her.

Once, a woman from the audience said to her: “Pazilye, I feel like I understand the deeper meaning behind your set.” It left Pazilye speechless for a while before she mumbled back, “I’m so happy to hear that.”

She added some fans into a small group chat on social app WeChat and named it “Pazilye’s Moms and Dads.” The majority in this group are young women, who chat about everything and share their daily experiences.

After a while, these women began using the group as a safe space to share their experiences in relationships and even, “their experiences of sexual harassment and assault.” Pazilye believes that the group “is a safe harbor where women can feel free to vent.”

Pazilye during a show in August (left) and her schedule in late September, 2021 (right). Photo Credit: Courtesy of Pazilye Parhat.

The Punchline

“How do you write your jokes?” Lang Qi, Pazilye’s fellow performer, once suddenly asked her.

“I can’t sit down at my desk and come up with material. It comes to me in a flash when I’m on the toilet or taking a shower, and I quickly write it down afterward. Then I try it out at open mic, and if it’s well received, I keep it,” she told him between mouthfuls of a sandwich, without looking up.

But writing jokes has never been difficult for Pazilye.

She’s always had a strong desire for self-expression and believes her wit comes from moments of real anger in her life. And no matter how good things get, life will always have its moments of anger and pain.

Most of the time, she just needs to relax and wait for the joke to come. In the beginning, Pazilye felt her audience never comprised the same people. From one show to the next, she never saw any old fans, so she could rely on the same 20-minute set for each performance.

But with more exposure and as her fan base grew, she started recognizing faces. Some fans followed her from set to set. It made her a little anxious.

“Some people have heard all my old jokes but I still haven’t come out with new ones — it’s still the same set. What should I do?” she says. A few fans reassured her: “Do you mean you only listen once to songs you like? We know creating new material is hard, and we’re willing to give you time.”

Though relieved, Pazilye says this interaction also led her to reflect on her creative process. First, she’s too busy to truly relax and wait for the jokes to come to her; but more importantly, compared with the past, her life now is far happier. She doesn’t suffer as much — or perhaps she’s too busy to properly recognize the suffering.

“A good sniper trains themselves one shot at a time, while a good performance artist gets better and better with each show,” says C+ Stand-Up Club’s founder Tian Long.

He also acknowledges the limitations of young stand-up comedians. “The same can be said of stand-up — it’s something you slowly perfect through experience. The more observant you become and the more experience you build up, the more things you have to say.”

Many actors regard Rock & Roast — a popular online stand-up comedy competition — as the ultimate peak to conquer. But Pazilye says she’s not “an ambitious person” and that she’s never aspired to be on the show. She just wants to continue what she’s doing and use it to make ends meet.

As the clock struck midnight, Pazilye rushed out of a theater in Sanlitun — the fifth performance of her day was done.

Heaving a sigh of relief at the entrance of the theater, she lit a cigarette. The excitement faded from her eyes and exhaustion gradually took over.

Her short-term goal is to write a special before the end of the year. It means that in the next few months, she’ll have to accumulate more than one hour of material.

She says, “It may blow up or it may not — maybe some people will like me, or maybe I’ll get heckled. Maybe I’ll get invited to Rock & Roast, or I’ll spend the rest of my life earning a few hundred yuan per set in small theaters. But so what?”

A version of this article originally appeared in Liquid Youth. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and published with permission.

Translator: Lewis Wright; editors: Zhi Yu and Apurva.

This article was originally published by Sixth Tone on October 29th, 2021. Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Hou Xueqi.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.