Everywhere’s a stage, but not all stages are equal. Some stages are empty of story and empathy, and not all performers are heard as loudly as others – or want to be. And in today’s world, everyone has a chance to perform on a global platform with audiences who show their appreciation via the number of likes, loves, thumbs up, smiley faces… All you need, is a cheap smartphone and an internet connection to achieve that social media buzz. Performance is performative in Kosovo playwright Jeton Neziraj’s Gadjo, and, where it is performative, it is clear it is being utilised for something else – the ego and a sense of self which is not being found in any other way. In this world, in long-term collaborator director Blerta Neziraj’s first scene of this show, young people, all dressed in black, some wearing knee pads and long socks, loll around on their phones. The boys dangle them between their legs like second penises, or the swords or pistols or shanks they might have had in times gone by (this is the way to fight the world now)- and the girls hunch over them as if they are harpies hanging over rooftops, and as if the whole world is contained in their little bricks of acid, plastic and digital superficiality. The scene goes on wordlessly, only broken by a sudden movement – to free a leg here or reposition a hand there – until the audience starts getting uncomfortable, bored even. Well, this is what it is like, watching people watching their phones. Then it is broken. Someone finds an catchy tune, everyone gathers around it, the ring-leader talks lovingly about how many followers and likes he has:

27 thousand views so far. You know which video got the most? The one where I’m on the toilet having a dump.

Sometime later, the group rap, their lyrics not too far from those of drill music videos, whose teenage singers are part of child and criminal gangs in Scotland. They perform to us or for the little box in their hand, the portal to stardom. Meanwhile – another artist sits near the kids (by this time, they are on a bus or in some other public space) she is a Roma woman (as opposed to being a Gadjo, a young European) who, to shut out the world, immerses herself in her music coming through her headphones and then begins to sing operatically with every ounce of her being. She does it for no one except herself. It is to support her loneliness (she has just been repatriated to Kosovo from Belgium, where she was accused of a crime she did not commit) and is wandering her homeland pining for the friends and family she has left behind. What ever else this play is about – bored youths hanging around in a poverty-stricken country which the EU has abandoned (with a young history of terrible war) – or the Roma who are just another reason for these kids to hit out and find a sense of purpose – or a misinformed witch hunt spread by social media and the media – it is absolutely about performance and art, the difference between them and how social media advocates superficial expression for likes and thumbs up and is all consuming.

In anyone else’s hands, this play, which is based on a true event where a Roma woman was wrongly accused on social media and in the media of kidnapping Kosovo children and was subsequently beaten by kids for it in 2019, could have become a victim fest only, or an intellectual expose of the Roma’s woman mistreatment. Or it could do a deep dive into why the kids of Kosovo are now like 1,000s of others in nearly every European society.

But context is everything. During the festival of which this show is a part, someone commented that Kosovo youth don’t want to know about the war. Today’s teenagers weren’t born whilst it was still being fought. What’s the framing of this play if it isn’t about young people (Kosovo has one of the youngest populations in Europe) who feel like it is being forgotten by the adults who are trying to build the country? (Independent Kosovo is around 15 years old, a teenager itself). And as a result, beneath this picture of juvenile delinquency in Neziraj’s play is an ominous darkness threatening to break on more than the bones of one Roma woman, and it is exacerbated by the false sense of fame and success social media can give, not relieved by it. The play is a study of bored youth. But this is not true to say of the Roma woman. The Roma woman inhabits the same terrain but lives in a different world.

Edona Reshitaj plays her with sweet innocence so that, even though she has suffered at the hands of Belgian police and other members of the general public, she still interacts with everyone with a degree of openness and trust. She openly acknowledges what she thinks is the interest of one of the boys from the gang, who sees her at a bus stop and decides he is going to screw with her head in an exercise of othering that borders on physical aggression. How is it that the Roma woman is wandering around happy and free in herself even when she is basically homeless, when he, who has a phone, a roof over his head and even girls, is not? His act of violence shows a community’s way of seeing the other and hating it because the other is happier, even if poorer.

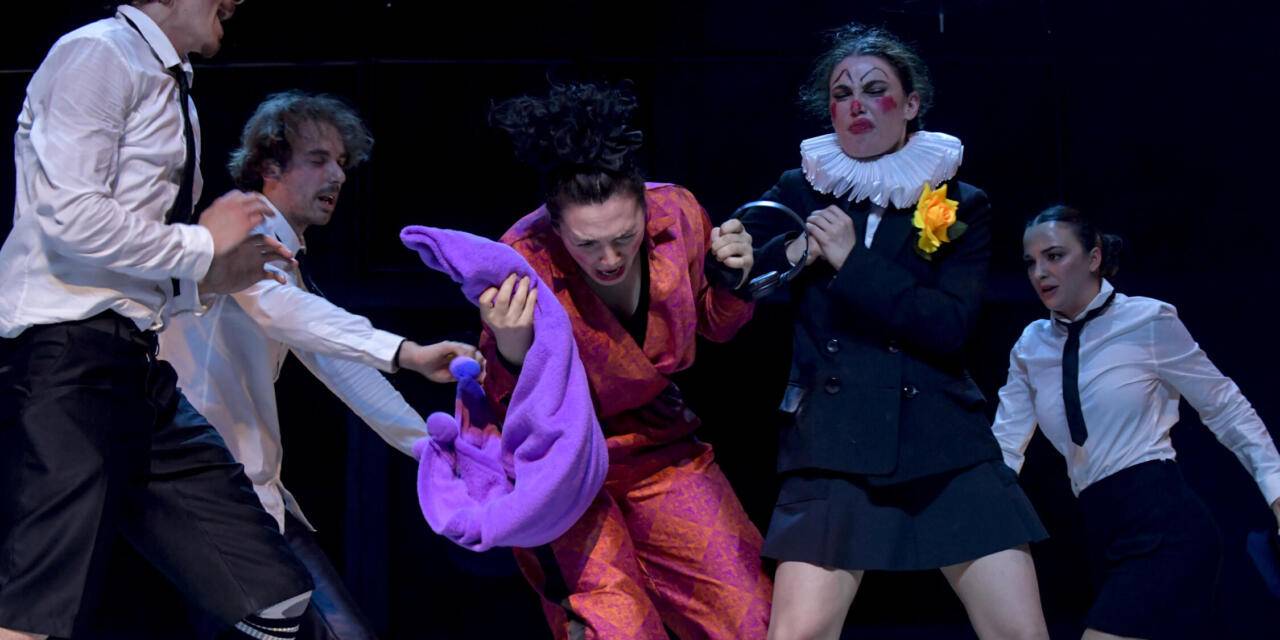

Ultimately, the play ends with the beating up of this Roma woman by this unhappy gang, which willingly believes that she is the man dressed as a woman who is kidnapping children. She is beaten to within an inch of her life. But even in this, Blerta Neziraj does not allow anyone in the audience or the young characters onstage to get any sense of enjoyment out of it. When the gang beat the woman up, they literally hit air and space. The Roma woman stands parallel alongside them, reacting to the blows. This beating doesn’t matter, is what this scene is saying. The kids don’t get anywhere, they don’t achieve anything when it is over, everything is still the same (apart from the fact they might get arrested – in real life someone was). A Choir onstage sings, “When we have assaulted all our enemies, serbs, gypsies, paedophiles, we’ll attack our mothers.” Was there ever an act of futile frustration so visibly portrayed? The same is true of the choreography in earlier scenes, prequels to the main beating. Here gang members grab the Roma woman and drag her in a repetitive dance sequence, before dropping her. Then they try again, and drop her again. What does this show? That the gang and the Roma woman are caught in ways of being that neither can free themselves from? That the repetition means that it is about the thing in itself, the act of violence, the ritual of it, and the feel of it as well as who it is against, like in A Clockwork Orange? It is highly stylised and highly performative.

For the Roma woman herself, of course, things have changed. Suffering wounds that are physical and psychological born down on her by a society that does not care, she retreats. And here something special happens. Jeton and Blerta Neziraj submerge her into her own inner dreamy world (a developing stylistic device in Blerta Neziraj’s work) one that is operatic but one, as she sails down a river in a boat under upturned umbrellas (symbolising magic, hope, protection?) and meets her ancestors, which gives herself back to herself and allows her to reclaim her homeland.She has a bigger heritage than these kids. And she is able because she has been able to develop an inner life rich in artistic expression, made apparent onstage by her singing for her own enjoyment and not for “likes”. The kids have no such luck – how can they have inner lives when they are so attached to their phones and likes on Youtube and false news? The full title of the play reads: Gadjo (the young europeans) post-drama. The kids don’t stand a chance, because they live in a post-drama world. Gadjo is not about a Roma woman or the kids who beat her up or the various actors from different social bodies who ignored or encouraged such behaviour – it is about the spiritual, cultural and intellectual health of Kosovo the teenager – a teenager that’s forgotten their parents.

Gadjo was part of the Kosovo Theatreshowcase held in Pristina 24-29 October 2023.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Verity Healey.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.