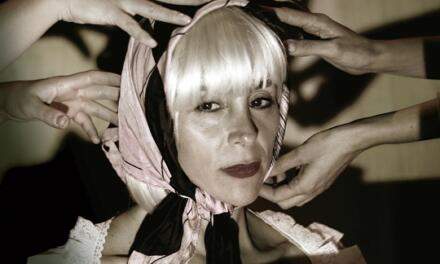

An interview with Edinburgh-based theatre-maker Flavia D’Avilia about dramaturgy and trans-culturalism.

Can you tell me more about your artistic practice, with Fronteiras Lab?

So, I call it a company for the sake of being easy but I really see it is as more of a network because we don’t have a fixed group of people who take part. It is more of a network of collaborators that come and go according to what I am doing.

So the idea started in 2011, that is when I founded the company, actually responding to a task I was set when I was on a production course in London. I went down to London for the six-week course at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama. I went because I wanted to learn a bit more about producing, and realized when I got there that everyone else had their own specific thing that they were working on. So, just for the sake of being able to respond to the tasks, I created a company – and I quite liked it!

So I came back to Edinburgh, registered it as a company, and started to move forward with it. So the idea emerged from the name, which comes from where I’m from originally, on the border between Brazil and Uruguay. As you can guess, the name Fronteiras, it means borders. That’s the word in Portuguese.

I grew up in this place that is a really really really interesting place, but you only realise that after you leave it, because it’s a very unique and incredibly close border. The two sides, the two towns, merge into one. The Brazilian side is called Santana do Livramento and the Uruguayan side is called Rivera, so they are not the same. You cross the road and the legislation changes, the currency changes, the language changes. Just across the street. And there is absolutely no border control at all. No check-point.

So I used to go school in Brazil in the mornings and go to English lessons in Uruguay in the afternoon. Which made it very amusing for me when I told people that I did study English abroad!

It is a very interesting place in that respect. Everything merges. The cultures, the traditions, the languages as well. There is a thing called Portuñol that is a mixture of Portuguese and Spanish, that people speak, not everyone, but some of the local colleges there have a bid with UNESCO to recognize that language is intangible cultural heritage. They haven’t managed to get it recognized yet, though.

So yeah, it is that general fusion of things which creates another thing that interests me. I wanted to transfer that to theatre. So this is why the company takes its inspiration from that place. Which doesn’t mean I have to work with Portuguese and Spanish of course. Being in Edinburgh, and having access to so many other nationalities and languages, I didn’t want to focus on a specific one. So the whole idea is, the aim of the company, is about looking for fusion – and it’s also what I’m researching in my Ph.D. – so it all comes together quite nicely.

So far we’ve done a little bit of text-based theatre and what I like to refer to in technical terms as ‘wanky theatre.’ Our first project Theatre Tasters was at the Edinburgh Fringe in 2012, which was a lunchtime slot formatted around a meal, so there was a starter-play, a main-course-play and a dessert-play. The starter and dessert were ten minutes long, and the main course was twenty. They were all written in English but from playwrights of different nationalities. The starter was an Australian playwright, a Scottish playwright was the main course, and a Norwegian playwright was the dessert. And even though they were mostly written in English, the last one incorporated a scene that, because I had actresses who were Italian and German, used all three languages at the same time. The same text, a monologue, done in Italian, German and English.

That was our first project. After that, I moved back to Brazil and created Fronteiras Explorers, and we managed to get a grant from Creative Scotland to do that. So I took seven Scotland-based performers to where I’m from for three weeks, for a residency, and promoted cultural exchange with local school students and local artists. We had both Brazilian and Uruguayan theatre directors coming in and doing workshops with our group. We were, very kindly, hosted in a community center.

I don’t know if you’ve ever heard of the gaucho culture?

Not at all, no

We are these kinds of South American cowboys.

That’s the closest comparison.

It is a culture that exists in Argentina, Uruguay and only the south of Brazil. Those three areas form the patria gaucha, the gaucho homeland, and we consider ourselves to be above the distinctions of Uruguayan, Brazilian or Argentinian. It is not officially recognized.

But that’s the identity?

That’s the identity. I don’t identify culturally with what you would think of as stereotypically Brazilian, like Samba culture, or football – I don’t do that. My culture is endless fields, big ranches, people on horseback lassoing cows.

Not the image you get of Brazil, not here anyway.

Certainly. That’s what you think when you think maybe more of Argentina for example. That’s what I identify with. So we have these community gaucho centers or centers for gaucho tradition. One of them let us use their space for the three weeks of the residency for our workshops and rehearsals, and they had a folk dance group, a gaucho folk dance group, who came in and did workshops with us on gaucho folk dance, and in the evening we did a Ceilidh with them. We gave them a Scottish flag, and to this day, they have outside their center the Brazilian flag, the Uruguayan flag, and the Saltire.

Would you say then that a lot of your work is really interested in communication, and negotiation? Barter, and something between languages? My understanding of language is that different languages can speak to each other, but there are also gaps that emerge

Yeah, that’s where the culture comes in. When the language is not enough anymore. That gaucho folk Ceilidh mash-up was my favorite part of the three weeks for that. It was so interesting to see how many similarities between things there are. Again, because gaucho tradition was pretty much invented, it is not that old, just about 90 years old. Brazil and South America are very young compared to Europe. So there are things like one of the dances there is called xote which comes from Scottish, and they have another dance called rilo, which is a reel, and they didn’t know that until we started doing the Ceilidh.

Were the dances very similar then?

They were both similar, to barn dance type things. So most of them will have mutated through Germany or Spain, because there was a lot of German, Italian and Spanish migration to that part of the country, as well as Portuguese. So they will be barn dances, and court dances, originating somewhere in Europe, and that have mutated along the way. The xote would have arrived there through German migration, because it comes from the German word for Scottish – schottisch

It sounds like you are interested in staging these conversations to different cultures. What role do the audience play in that, are they part of it, are they spectating on it?

They were definitely participating in it on that project, because we didn’t want to do the thing where we come over there with a group of European performers, and tell them how to do their own culture. I felt I had some leeway though because I was from there

A degree of access at least?

Yeah. So we kept a blog throughout the project, which is still live. I was blogging, and each of the performers was blogging, to get a perspective of everyone that was involved in it, and I think in one my first blog posts I mentioned my nervousness, feeling like I belonged to the place but that I also didn’t at the same time. In a place like that, which is quite a small and rural town, you can be seen as a traitor if you leave.

Then you turn up with a group of foreigners.

Tricky

Yeah. So I did invite local people to be part of the group, two Brazilian students joined us for the three weeks, helping us to shape the final piece as well. They didn’t want to create their own solo piece, as part of this site specific performance along the border that was a series of different solo pieces. They didn’t feel confident enough to do that, but they were there to help out.

We also had barters with the local community, because we wanted to know what they wanted to see reflect back.

I wasn’t entirely sure what the response would be for the actual piece in the end. And because it is such a small, and isolated place, we don’t really have theatre, or a theatre-going culture. There is one theatre building on the Uruguayan side that hosts some touring productions, but it is falling apart. But they responded very well – and one thing I’ve learnt from the work I’ve been doing is to not underestimate my audiences. We did it and I think maybe forty people turned up, and because it was done as a promenade piece, people started following along the way. We managed to keep their attention, to keep them with us, and just two or three months ago I got a message from someone who saw it – three years ago – saying it was still very vivid in their memory, and that they wished more people would do things like that – so, yeah, that was quite good.

The same thing goes for the next project we did, La Niña Barro, which was a devised piece based on a collection of poems by a Spanish writer. It first opened at the Fringe in 2014, and we had lots of problems with that one, we had to cut the run short because one of the performers’ dad passed away, and the show was censored as well, because it had nudity in it. But, the interesting thing, in terms of the audience for that one, is that I chose not to translate it. I wanted to keep it in Spanish, with no subtitles. It was such a highly visual piece, and there isn’t a lot of text in it. The main actress, she’s Spanish, did offer to learn the text in English but I wanted to challenge the audience.

It had a mixed reaction. Quite a lot of people said they didn’t feel they needed to understand the words to follow the piece, but they would have liked to know. No one absolutely said they couldn’t follow it all. I’m working on bringing that one back here again – it has been touring since, mostly in Spain. We did take it to South America, to Brazil and Uruguay, and to Miami as well. I would like to bring it back to Scotland now, for a proper run, and I think I’ll provide a translation with the program, but I still don’t want to put subtitles in, because I want people to really look at the piece.

And I think this work is possibly the most relevant to your project, because there was a lot of dramaturgical work involved in that one.

Great. Focusing on that production maybe, how does dramaturgical considerations come into your work?

I suppose thinking about dramaturgy didn’t come into the first project. It was just straightforward. The writers sent me their plays and I directed them. That was it. The only alteration we did was changing language in the dessert piece, but I don’t consider that dramaturgy, more decoration perhaps.

There was a lot more dramaturgical work involved in the borders project because we had to find a way of stitching those pieces together. All of them had, as a running theme, a response to the border. So it wasn’t difficult to do, and it was a collective job. It was all of us sitting together, chatting and deciding on the running order, and why. Each performer had spots they liked along the border so we had to think about whether we were going to take the audience on a linear path or a back and forth. So yeah, that was the dramaturgical work.

That seems there, in that project, to really fit with your working processes. Of it being about a collective effort. Maybe someone assigned the role of dramaturg would be have been disruptive in that context?

It would have been different. Yeah.

And La Niña Barro was dramaturged by myself. One day I would like to have a dramaturg working with me though, but you know how it is, when you work with a small largely unfunded company you end up producing, directing, stage managing and dramaturging.

Was that something you were really conscious of when making the work? In the same way that you might divide directing-work and stage management, would you be dividing the dramaturgy-work from the directing-work? Or was there more of a blur there?

I never planned for it to be this way for that show, but it got to a point in the devising process where it became quite clear that the work needed dramaturg and that I would be the one who would have to do it.

Another interesting thing is that, the figure of the dramaturg is associated with German culture, and I haven’t encountered it in the other cultures I’ve worked with.

Yeah, I was curious to ask about whether that figure had a place in Brazil for example?

To be honest I know very little about the Brazilian theatre culture because my education was in Scotland. I learned a bit when I was back. Dramaturgs don’t exist, stage managers don’t exist. You get stage crew, the very defined role of the stage manager that we have here doesn’t exist. You get three or four people backstage who will tag-team it. There are less defined roles. The three that you have, perhaps, are the director, playwright, and actor. Everything else is just…

Up for grabs?

Even the technical staff or front of the house staff, they are just students learning to be actors or directors or playwrights.

Brazil is very big on visual arts. They have a tradition of good visual artists, particularly from the beginning of the 20th century and onwards. There is really interesting work done there.

In theatre terms, I kept trying to go and find something new to watch, but found that the 80-85% of what was on stage were translations of classics, either European or North American. The whole culture of new writing and devising seems still very insipient in Brazil. And the little bits that I found were all visually stunning, aesthetically amazing, but dramaturgically they made no sense – to me. So I found that very interesting.

I think there is a little bit of that in Spain. When we were devising La Niña Barro and it became clear that I had to do the dramaturgy, it was partly because I didn’t have the money to fund someone else, but also because I couldn’t find a dramaturg in Spain.

So do you view dramaturgy as like a practice of making sense of a work? Directly tied to a narrative? I guess with devised work there isn’t typically as strong a narrative, or at least that narrative isn’t so linear

Yeah, not a linear narrative. With our piece, there is a journey, a very clear journey, but that’s how I view dramaturgy, yes – it’s a tool to make the piece make sense. Because sometimes I think it is quite easy for us to get tangled up in our own beautiful ideas, and forget that it has to make sense to someone who wasn’t in the rehearsal room with you. People are clever, though, they understand more than you might think.

I guess it is about finding a balance, somewhere between spoon-feeding and total confusion.

With that piece, there are two very distinct interpretations that we get for the work. They have more to do with where you are at in your own life when you see it. Some people view it as a very positive piece, and at the end, they describe it as uplifting, and some people say that was horrible, I am in pieces. Even within the group, we have that difference. I find it quite a sad piece, and one of the performers sees it as more about overcoming challenges and finds it uplifting. Now we chose to leave it as it is, but yeah, it seems to reflect where people are at in their own personal lives when they see it.

Do you think there’s something particular in the way you’ve structured the work that allows that openness?

I think so. I think that has a lot to do with how I ended up dramaturging the piece. As I said, there is not a lot of text in it, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t a lot of dramaturgy. It is a very silent piece. It gets the audience into a meditative state, and we manage to get to that place within the first ten minutes of the piece. Within the first few minutes, you hear that silence. The work is based on a collection of poems, and we’ve had audience members say to us that they could feel that poetry in the silence.

Given the work is based on a collection of poems, how did you stitch it together?

The poems are all in a blog – the writer is a personal friend and one day she mentioned she wrote poems. I went to read them and they just spoke to me. She had twenty-eight poems about this one …character, called La Niña Barro – the girl made of mud. They are beautiful, and a bit of a punch in the gut at the same time. There are some that are sad, and some that definitely have this sense of overcoming to them.

I remember finding them beautiful the first time I read them, but I didn’t have the idea to make a theatre piece out of them until I was back in my home town. There was a poetry-jam session that I got invited to, but again it wasn’t people reading their own work but reading classics, and I wanted to read something new. When I read these poems out loud I realized how performative they were, and I went back to my friend and asked her “can I mess about with your poems?”

What I did then was I took this collection, these 28 poems from her blog and into a word document. Then I sent the whole anthology to these two performers, and I asked the performers just to read the text and focus on the strongest images and motifs that emerged for them. For the next four months we worked that way, we chucked the text completely away. We worked with the feelings, the motives, the images, the colors, all these things that came out, but not the text. We were filming it all, too, because I was back in Brazil and the girls were in Spain. I would send them tasks, they would do a workshop and send me a video, then I would feedback to them.

How was that as a way to work?

It was good. It came out of necessity, but it meant the whole process was documented.

Yeah, and the amount of time that would give you. The ability to sit back.

It was great. When I went for the last month to work with them in Spain, even though I had the same information as them, I hadn’t been in the room, and so I felt like I was coming in with a completely fresh perspective. That was great for us, because they were so involved with it that they couldn’t quite think clearly anymore. That was essentially when I sat down to make sense of the piece.

The two performers, one of them plays La Niña, and the other plays a mbira (a Zimbabwean thumb piano) and she sort of shapes the clay-girl. That’s the one who you either see as a mother figure, or as someone who is quite manipulative. It makes you question to what extent we make choices in life, and to what extent we are shaped.

They always remember, every time we take the work to a new place and there’s a Q+A or something, me saying to them after coming into rehearsals. “Right now you are just two women doing random things, how do we make this into a piece?” And that’s when we went back to the text, started lifting lines from the poems that I either could see very clearly on the physical score, or that contrasted very clearly with the physical score. That became the script, if you like, but a script of only twenty-four lines!

And that script had a generative relationship to those movements?

Like I said, we started with the poems, but then we really worked with images, and didn’t learn any text for four or five months. And then we went back to the text, and chose the lines that eventually made it into the script. That became the dramaturgical process, going back to the text and stitching it together, asking ‘how does this make sense?’, ‘how do we make this make sense?’

There is a script to it, but it is not a play. The author would never call herself a playwright, and even though we advertise it as ‘La Niña Barro by Marta Massé’, she didn’t write the script. She created the character.

And then you and the actors sculpted the performance, the result.

There are two things I find really interesting. First of all, that distance between you and the actors, because dramaturgical relationships are often characterized as being able to operate at a distance. You described the two actors as being caught up in the process and you being able to sit back. I’m interested in what you think about that distance, and whether you felt it was productive in allowing you to take on a dramaturgical role

I think so, I think so. Like I said, something born out of necessity but that was very productive for us, that was very beneficial. It is a big pleasure for me to just unleash actors. To see what they can do. I think as a director I see myself more as a dramaturg, or a mediator, or even a translator.

When we were doing Volante, the first thing I said when I came into the room was ‘I am not a director with a vision, I have no idea what is going to come out of this, you guys are going to give me some material, and I’m going to help you shape it.’

That was an interesting one again, because we had Jen McGregor as the playwright. When Jen asked me to direct it, I had to ask her why, because I hadn’t worked with text-based theatre for five years. But that’s what she wanted, she was interested in seeing how the way I work might shape how she works as a playwright. She had written a few scenes when we workshopped it, and then the rest came from me working with the actors. So I guess Jen then both wrote and dramaturged her own play at the same time.

I think that’s a lovely way to work with people, and in this context, in a U.K. context, is pleasurable in part because it feels quite different. In terms of what you were saying about letting actors loose, I enjoy working in that way as a playwright, because there’s so much potential there – I don’t know what’s going to happen! That’s great! That’s also the reason I enjoy occupying a dramaturgical position within a production, because it is about not knowing what’s going to happen, yet still trying to guide it in some way.

I see the dramaturg as the person who both helps make sense of the piece, and has that distance, who is a bit of an outsider, who has the same information as everyone else but doesn’t have that emotional attachment. That’s so important, and it is something that is definitely underplayed in Scottish theatre. Directors and playwrights that I speak to are afraid of the dramaturg, are afraid that they are going to steal their show or something like that.

But they are there to help. A dramaturg is someone who will see the best bits and lift them out on the stage.

I guess there’s the idea of the dramaturg as a critical figure. I think people often assume that’s about negativity, when actually when I work I’m more interested in what attracts my attention, about the qualities I like, rather than finding bits I don’t like or that bore me and drilling into them on repeat.

I would like – originally, my idea for my Ph.D. was to have a dramaturg in the room with me. I’m going to run a lab with actors from diverse cultural backgrounds. My original idea was to devise a piece and have a dramaturg, or maybe two, with me in the room, although I don’t think I could totally switch off my brain from thinking about it

Well, at least maybe you could defer those thoughts.

Exactly. It is useful to have that extra pair of eyes because they will see things that I’ll miss. I did think initially to have two dramaturgs from different cultural backgrounds, one who was Scottish, and one of a different nationality because it would be different…

They would pick up on different things

But because of the way academia works and time constraints, I’m not actually going to come up with a piece at the end anymore. So I’m just running the lab to try and come up with a toolkit for people wanting to work with a multicultural group of actors. There would be no need for a dramaturg now, but that is the kind of thing I would like to do in the future. I’m actually, this is not official yet, but I’m trying to put together the next big project, which is a writer-focused project. I’d like to offer a residency to writers who are interested in working with a different languages or cultures, in which the writer would come up with three projects for me; a play, an adaptation, and a dramaturgical project.

Volante is actually the first of these projects, I’m piloting it with Jen, working with Italian language and culture. She is working on an adaptation now of Niccolò Machiavelli’s The Mandrake, and we’re still debating what the dramaturgical project is going to be after that.

I really like that sustained relationship you and Jen will have. That feels rare. That a writer and director can work together so repeatedly but in very different ways.

Yeah. Jen and I have been friends for years and we have worked together on lots of different projects, but we have never worked together in this capacity. So we had co-produced and co-directed things before, but I have never directed her writing, so that was quite interesting because our artistic views are very different. It was an interesting clash, and this idea came out of that.

I think that’s where the joy of your work seems to come from, from those clashes of very different perspectives, including on how you make work?

Yeah. Because even if you are working with people whose backgrounds and training are very different from yours, it is the joy of finding the similarities that interest me.

For sure, I think if you only work with people who are so similar to you, you tend to end up with the same kind of work, or even know what that work will look like before you’ve started.

Yeah. I think that is something that is plaguing Scottish theatre at the moment. This is me committing career suicide right now

It’s okay you can redact it later if you want!

I just find that everything I go to see is very samey, in the main theatres. Everything seems so standardized and I think that part of that is the same people working together and churning out the same kind of work. Everything is very standardized.

People who might have all gone through similar institutions perhaps too?

Yeah.

It’s interesting, though. Can you tell me a little bit more about your Ph.D.?

Yeah, so it is on a thing called Syncretic Theatre. Syncretism is a term borrowed from religious studies that describes a kind of fusion, a fusion based on similarities and not differences. You find syncretism in new world countries, in the Americas, when African people were taken there as slaves and they were not allowed to practice their own religions, so they found a way of fusing their own religions with that of the catholic saints. After all these years, now, if you walk into most Brazilian houses you find a little shrine in the corner containing both Christian/Catholic imagery and African/Santeria/Candomble/Umbanda. It means you end up with things like where the patron saint of Brazil is a black version of the Virgin Mary, and Yemanja, African goddess of the seas, can be found represented as a white woman in some places. They have both been syncretised.

There is a Munich-based scholar who coined the term theatrical syncretism, that’s where you find fusions in theatre.

There is a very fine line between what is syncretic and what is multicultural, transcultural or intercultural – whatever you want to call it, but I do like the term multi-inter-transcultural.

This scholar, Christopher Balme, says that he sees syncretic theatre as being more focused on indigenous playwrights and directors, and what he calls cultural texts, things that will only make sense in that culture

Because they have that locality?

Yes, so you could say that kilts and bagpipes are Scottish cultural texts, whether you like it or not. They might not make sense taken outside of that context.

So Balme recognizes syncretic theatre as theatre that features cultural texts with the due respect given to that cultural context, instead of more orientalist pieces in which theatre-makers decorate their plays with bits that are cherry-picked from other cultures.

But even so, in all of the work he surveyed, and in the other literature I’ve read, you are always dealing with a classical text translated and adapted into another culture. So you’re looking at Shakespeare, Ibsen, Chekhov performed by Maori actors, or within the tradition of Noh theatre, or you do get the occasional folk tale from those cultures that gets westernized. I haven’t found that in devised theatre yet, so that’s what I’m doing.

I also have moved away from Balme’s definition of indigenous. I see it as ‘being from a place.’ So, if I am looking for indigenous Scottish writers, I’m not necessarily looking for Gaelic writers or people with Celtic blood

But born in Scotland?

And/or who identify culturally as Scottish…It’s a project that has grown arms and legs and horns! Because I find it very exciting, which is a good thing I hope…

I came across a little book called Theatre and Migration by Emma Cox. She looks at theatre made by migrants who are now living in the ‘center,’ people like me. Who have migrated from previous colonies back to the matrix and are now making their work here. Most of the pieces she is looking at are highly political verbatim pieces, and again, I haven’t really seen much in terms of what I do.

But I’m looking at this counter-colonisation of theatre. So I’m not looking at people who are migrating back to what used to be the empire, from what used to be the colonies, and sort of, carving their own space in it.

There’s another book I came across, about trans-culturalism in the work of David Greig, and the most interesting idea was in an essay by David Pattie, in which Scotland as a non-place came up. I started thinking whether this was why I ended up in Scotland and doing this sort of work in Scotland. For such a small country it is very fragmented identity-wise. You do have the usual tartan and shortbread and stuff, but most people don’t like that, they will actually deny that. If I ask someone what is their cultural background they don’t tend to have a certain answer but define themselves against the English or against the tartan or against the shortbread

So that identity is formed through opposition in some way?

Yeah, and it is a perpetually liminal state of identity. I thought maybe this is why I find it such an interesting place to do my work, because I feel like I can just walk into a Scottish theatre and just do this stuff. So, you know, there’s nothing preventing me from calling myself a Scottish theatre-maker, and I’m not ashamed of claiming that.

Originally published as part of talking dramaturgy. Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Andrew Edwards.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.