Stalkers, heroes, and cult leaders. Depression, maternity, and citizenship. Edinburgh Festival Fringe saw no paucity of intriguing subjects tackled by solo performers this year. These works, revolving around the magnetic presence of their creators, often put autobiographical experiences at their center, but not without tapping into questions of universal relevance.

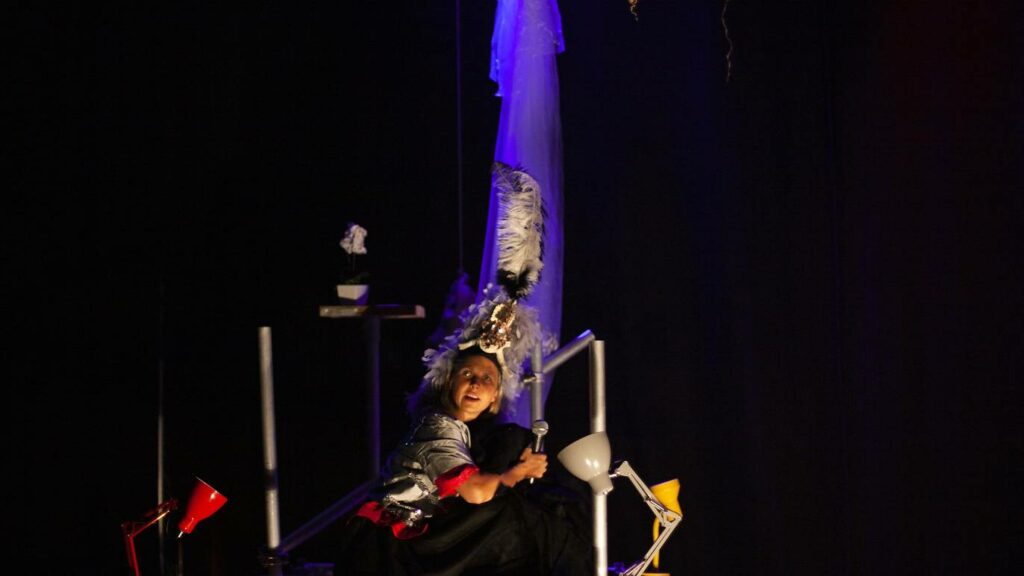

Caroline Horton’s All of Me (Summerhall) is an impressionistic account of her experience with depression and suicidality, as well as a meditation on how she has kept afloat since then. Self-consciously elemental and raw, the piece borrows from the myth of Eurydice and imagines depression as a sister figure with monstrous elements. Of particular note is the way it begins and keeps returning to that beginning: Horton apologizes repeatedly that the performance will fall short of expectations in more ways than one, and starts telling about a former version of it, which was substantially different. The ghost of this earlier draft lives on in the current production, much as the ghost of her depression still haunts her. With fractured language and cacophonous sounds, Horton enacts a mythical journey into the dark corners of her mind—a journey that proves greater than the sum of its scattershot parts.

Caroline Horton in All of Me at Summerhall. Photo: Holly Revell

I’m a Phoenix, Bitch by Bryony Kimmings (Pleasance) charts a similarly inward trajectory, but on a far more lacerating register. Kimmings’ detailed chronicle of how her life “burnt to the ground” in 2015 begins like a fairytale, but quickly descends into an underworld of unexpected darkness and shocking perseverance. The chronic illness of her toddler boy, we learn, triggered Kimmings’ life to spiral out of control, plunging her into a psychotic period that tested her strength in increasingly exacting ways. The resulting work is a deeply honest, vulnerable performance that turns into a ritual of self-affirmation and recovery. In both making use of heightened artifice (tongue-in-cheek musical acts, immersive projections, on-stage costuming) and occasionally distancing herself from it, Kimmings treads a fine line that pays off greatly. Her medium becomes the only language fitting for her purposes: “I can’t describe it with words,” she says of her unraveling, “so I’ll show you.” So she does—exquisitely, shatteringly. This psychological epic may well be the best thing I saw in Edinburgh this year.

As a kindred narrative of trauma, Baby Reindeer (Roundabout) recounts Richard Gadd’s harrowing experience of having been stalked by an older woman over several years. What might have been a straightforward story of a terrifying ordeal is made even more complex as Gadd brings to the fore how his fraught relationship to his own sexuality and to his burgeoning career as a comedian had a bearing on the progression of events. Gadd’s dazzling storytelling derives from several factors: rivetingly fast-paced projections (showing factual evidence of his stalker’s messages), disarming use of an in-the-round space (featuring a revolving platform), and Gadd’s charismatic and confident physicality. Even as he signals that he has this narrative under control at the present moment, he does not refrain from sharing with us his vulnerability in processing and conveying it. This profoundly disturbing story of a life under continual threat ends up deploying its communal medium as a means of hinting at Gadd’s resilience.

Richard Gadd in Baby Reindeer at Roundabout. Photo: Andrew Perry

In First Time (Summerhall), Nathaniel Hall gives an entertaining, powerful, but slightly saccharine account of his life as an HIV+ queer man. Consisting of several episodes that pertain to how he has caught the virus at the age of 16 and lived with it ever since, First Time revolves around the stigmatization of HIV, as both a psychological and social phenomenon. The piece gradually becomes an elegy for victims of AIDS and a celebration of his, and others’, triumph against it. Even though the multiple layers of Hall’s performance do not always cohere meaningfully, there are some memorably strong parts to his frank self-portrayal. At some point, for instance, Hall reads out a long list of things he did (and didn’t do) after his diagnosis, with a deadpan eloquence that resonates beyond his time on the stage.

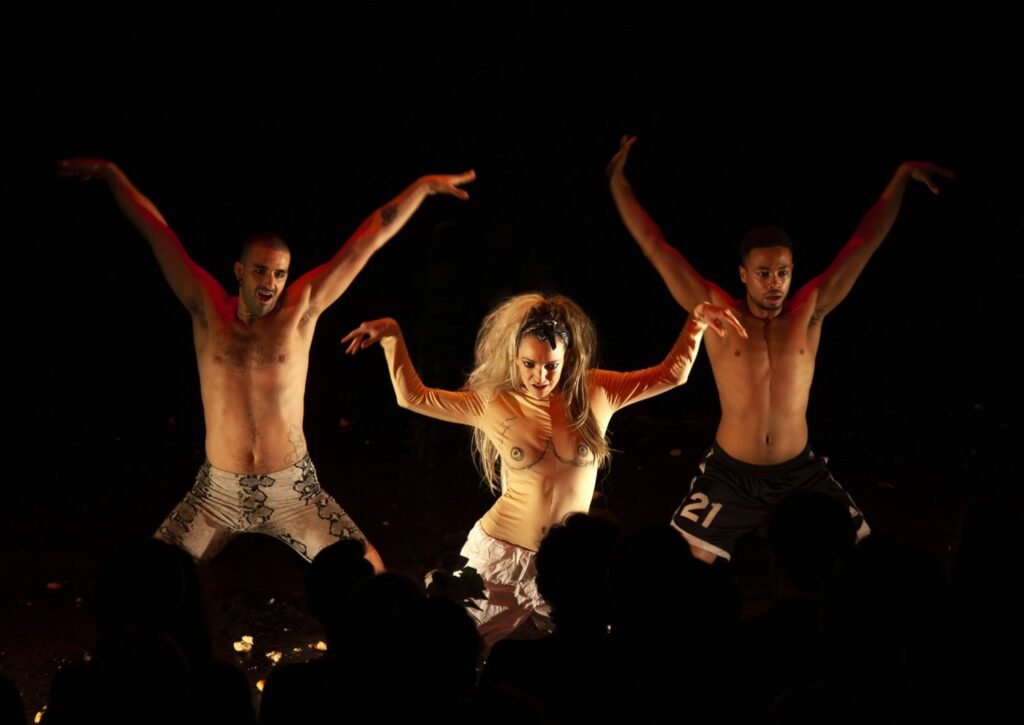

Lucy McCormick’s not-so-solo Post Popular (Pleasance) is, at its core, all about what its title suggests: the performer’s anxiety-ridden experience of creating a new piece after her smash-hit from Fringe 2016, Triple Threat. Yet these reflexive energies are fronted by the self-consciously ludicrous attempt to “re-enact” heroic women from history—well, if not all of them, then four. Accompanied by her unruffled wingmen Rhys Hollis and Samir Kennedy, McCormick does everything within her power (and then some) to create a brazen, reckless, and positively ridiculous hour of musical turns, audience participation, and “alternative comedy.” The looseness of the show captures something of the mindset of one who has recently done something great and is now brainstorming to build onto that. This intentionally meandering search for inspiration concludes when genitals are exposed and our real heroes are found deep in their vicinity. Crazy, indeed, but a lot of fun on the whole.

Samir Kennedy, Lucy McCormick, and Rhys Hollis in Post Popular at the Pleasance Courtyard. Photo: Holly Revell

In My Mum’s a Twat (Pleasance), Anoushka Warden narrates how she lost her mother to a cult at the age of ten. Yet there is more in this piece about Warden’s own growth as a teenager and her changing relationship to her family than about her mother’s upended life. Though the text is strong and frequently glows with sharp humor, Warden’s own performance feels clunky and stagnant. This wacky coming-of-age story goes to some exciting places, but its effect on the audience would have been far more pointed with a more agile actor and inventive direction (as must have been the case in its run at the Royal Court Theatre in January 2018).

Scottee’s Class (Assembly) also turns its gaze on a troubled childhood, but does so with a thought-provoking edge. Scottee blends his affable sense of humor with daring social critique to brew this confessional account of his upbringing in poverty—and of the ways in which his working-class background has scarred him incurably. He begins with wry comments and hard-hitting recollections and ends up—quite literally—holding the mirror up to his audience. “Why are you here?”, he asks, “What brought you to a show about the working classes?”. This plea for self-questioning and self-criticism lands in nicely, as it follows in the trail of Scottee’s warm-hearted engagement with the audience throughout. Even though the work’s structure may feel disjointed at times, its admonitory thrust is often legible, and its quietly elegant design is a thing to behold.

Scottee in Class at Assembly Roxy. Photo: Holly Revell

Chris Thorpe’s Status (Assembly) unsettles the reliable valence of autobiography. Directed by Rachel Chavkin, this post-Brexit piece deals with the politics of citizenship, especially in the context of Britain’s imperial past and its historical claims of cultural superiority. Following in the footsteps of a character named Chris, whose story of soul-searching may or may not overlap with Thorpe’s own experience, we are invited to think about the problematic of nation-states as it drives one man to extremes. An increasingly bizarre series of events leads to a conclusion that is unanticipated in its argumentative stance and somewhat rough around the edges. But Thorpe’s infectious energy is admirable from start to finish, and he makes sure that the uncertainty surrounding the veracity of his tale lingers beautifully.

The imprint of national politics is also visible in Yeşim Özsoy’s House of Hundred (C Aquila), an eclectic journey through the history of an aged, and now demolished, mansion in Istanbul. Through a combination of film, documentary interview, and live music (performed brilliantly by Kıvanç Sarıkuş), Özsoy attempts to tell the story of the mansion’s many inhabitants through the perspectives of the objects and animals that accompanied them. In giving voice to these nonhuman beings, Özsoy delivers an angular performance of comic tenor, but the details of her colorful narratives do not always come across with clarity. Despite the inherent richness of its source material, House of Hundred offers an unnecessarily oblique look at Turkish history in its struggle with modernity.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Mert Dilek.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.