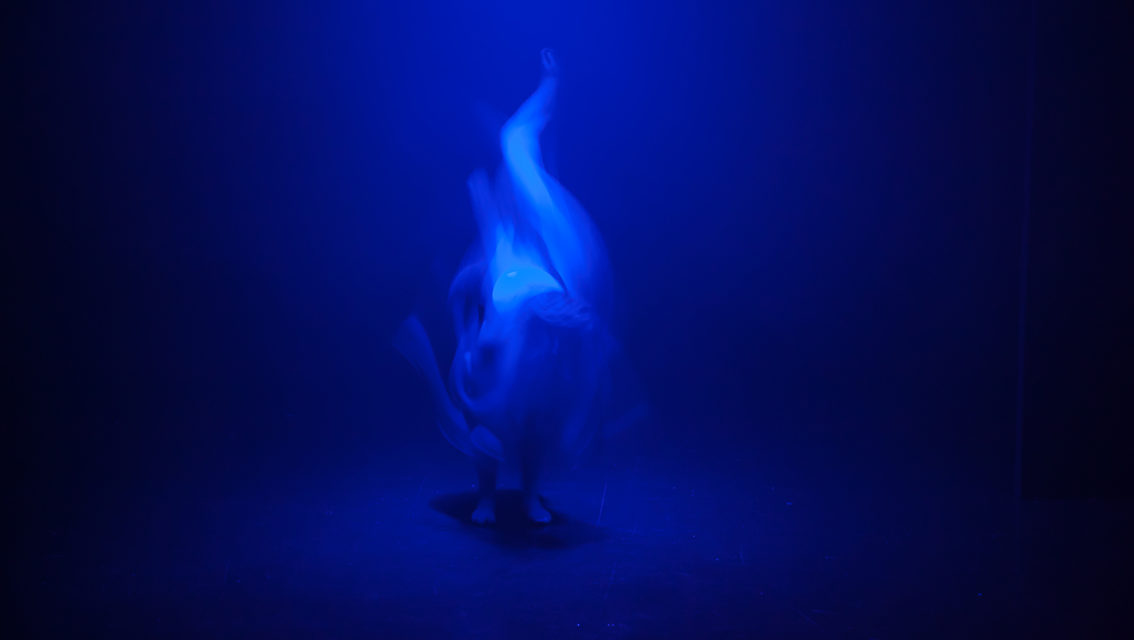

The light fades to a darkness more intense than a starless night on a country road. As the eyes slowly adjust, two barely discernible figures appear in a vast void, vanishing as mysteriously as they appeared. Over the next 40 minutes, the space before us shifts and changes, through a series of seven “visual haiku,” re-configuring the space so that at times we seem to be looking into an infinite space, at others closing it off so that there is a solid wall of light directly before the front row. Like a haiku, each sequence is brief, exploring one theme through intense poetic imagery. In between, the audience has a chance to rest and reflect, while partially blinded by a single light. I notice some audience members with eyes closed, keeping their eyes adjusted so that they are ready for the next revelation. Dark Matter is a workout for the eyes, exercising muscles we don’t often think about, showcasing the act of seeing, giving new meaning to the phrase ‘trick of the light.’ Two performers are glimpsed only momentarily, vanishing like ghosts, their bodies sculpted by beams of pale light in stillness, mirroring or sudden movement. Sound design by Jeremy Mayall, ranging from monumental music to the distorted communications of astronauts, enhances the epic proportions of the mise en scène. In one haiku we experience a cinemascope screen full of dark shifting patterns, shapes and textures. In another, a curtain parts to release millions of light particles speeding towards us. At other times we lose sense of distance and proportion, as we seem to be floating in a vast emptiness. Is this the darkness of the deepest sleep, or of Te Kore, the void which preceded the creation of the universe? Is this outer space or inner space? This is a meditative work, where shifting patterns of light and form enable us to contemplate the nature of matter itself.

This show is Dark Matter, the work of one of New Zealand’s leading lighting designers, Martyn Roberts. For the last twenty years, Roberts has designed countless mainstream theatre productions alongside radical experimentation with his own company afterburner. Dark Matter evolved as the creative component of his MFA in Theatre, completed at the University of Otago in 2014. Its first public performance in the Dunedin Fringe Festival (2016) was described by critic Hannah Molloy as “hypnotic” and “mesmerizing” and it won two Fringe awards. Now, performed in Wellington as part of the New Zealand Fringe Festival, Sam Trubridge describes Roberts as “New Zealand’s master of painting darkness over darkness, of sculpting the darkness as though it were a thing of immense solidity and form.”

DOD: Can you tell me about the inspiration for Dark Matter?

MR: The inspiration came from always being intrigued in my work with the transitional moments between scenes. I’ve always loved directors that treat those moments as just as important as the scenes themselves. Those moments are blackouts, or moments where the lights dim down and come back up. I wanted to take more care with those moments than with the scenes themselves. And that led me to develop an MFA proposal that examined the liminal space in between where you can see something and where you can’t.

DOD: Why seven “haiku”?

MR: What I love about haikus is that they’re these lovely little splashes of a fleeting image or fleeting emotion or fleeting thought in the written form, and in many ways, this is what I’m doing visually. An audience understands that they can create their own meaning from what they’re seeing.

DOD: What particular challenges did you face as a lighting designer in making Dark Matter?

MR: Getting a dark space. When you want darkness so dense that you can’t see your hand in front of you there are certain rules and certain limitations in venues around exit signs and so on. So there’s a fine thread of where can we pitch this, so the audience is safe in terms of the health and safety of the venue but where the venue is prepared to help us limit the amount of light, and when I say limit, I mean eliminate the light.

DOD: How much input did your collaborators have in the finished work?

MR: They always have input. Obviously, I had very strong foundational ideas but the performers and the technical manager shared their ideas. We go into the space and we interpret the space, we have to do it collectively. Always the space will tell us something different.

DOD: Has making this show changed the way you think about lighting design?

MR: Yes it has. Making this show and the process of doing my masters has opened up the whole area of using light as an architectural form, treating darkness or blackness as a substance in its own right. Those are things that most lighting designers are aware of, but I’ve arrived at a point where I’m really interested in playing with those substances.

DOD: What was the most surprising reaction you had to Dark Matter?

MR: The range of individual responses from an audience. I really enjoyed listening to the responses of what people think they saw, what they felt, and all of it is relevant.

DOD: How have other lighting designers responded to the work?

MR: They have greatly appreciated the simplicity of it, the level of intensity and the interpretation of the space. They love the idea of light being the key performer. It’s led by lighting as opposed to narrative or movement.

Following the performance, the audience emerged blinking into the pale sunset of a late summer’s evening. There is a sigh of awe as we witness a perfect double rainbow across a cloudy sky. At this moment, nature seems in harmony with art as we contemplate finding new ways and seeing and thinking.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by David O'Donnell.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.