… when no one is willing to listen, no one you could tell, no one you could talk it over with to set you free, the only thing left is art as a way of reaching other people and communicating to one, two, or three other individuals.

Taigué Ahmed

How do we communicate the unspeakable? How can we find a language for traumatic experiences like war and the life-threatening conditions that come with it? Taigué Ahmed, a dancer and choreographer who grew up in Chad, uses dance as a medium to communicate his experiences with an audience.

He also initiated several dance workshops in refugee camps to transmit his knowledge of movement and exhaustion as a kind of therapy. In this interview conducted by Jean-Baptiste Joly, director of Akademie Schloss Solitude, Ahmed discusses his practice–which is both artistic and therapeutic–and the difficulties of staging a play originally developed with refugees abroad.

Taigué Ahmed: I have some good news. We’ve been accepted for grant funding from the German Cultural Foundation’s TURN program.

Jean-Baptiste Joly: Congratulations!

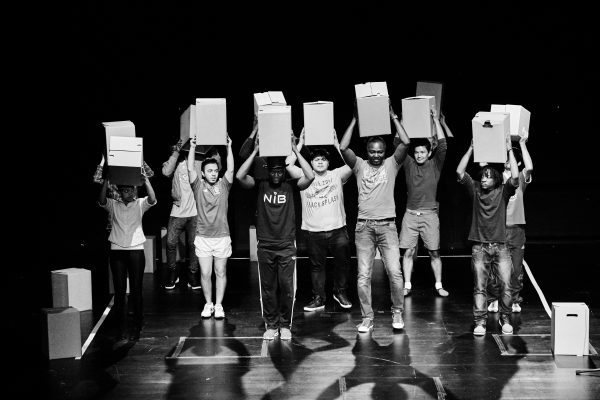

TA: The funding is for an original creative project with five Chadian dancers that I’ve been working with in the Central African refugee camps in Chad. The dancers on stage represent the refugees; “represent” means carrying their stories, carrying everything to do with their daily lives, with their stories today, whether it’s refugees in Africa or in Europe. This is such a contemporary topic! We really need to let people know what is happening in the camps, and also what is happening outside the camps. That is where we have got to so far.

JBJ: So, the people dancing on stage are professional dancers?

TA: They are professional dancers who are working with me on this project and whom I have trained in my pedagogical approach. But they are also dancers of different styles: pop, modern dance, coupé décalé, which is another African dance. The music will be composed by musicians from Germany. The same goes for the costume design. For the creative direction, we will have external people coming from France to collaborate with us on the project. So, there will be a bit of Europe and a bit of Africa.

JBJ: And do you have German partners for the project?

TA: Yes, our partners in Germany are the Munich Kammerspiele and the Düsseldorf Tanzhaus. There should be some French partners joining, too.

Image by Ramona Reuter

JBJ: Does this mean that you are representing the situation in the camps using professional dancers?

TA: Yes, that is what we are doing. We are representing a situation where all kinds of people have ended up or been shut up in the camps. Outside the camps, we don’t see refugees, and we don’t see what really goes on in the camps. The dancers and I did a month of research. Next, the creative director will work with them for ten days. He will live with the refugees, share their daily lives, live with them, see what goes on, make a little documentary, produce videos.

“…it’s all part of being an artist. Being caught up in an idea, expressing yourself, performing as yourself and on behalf of others.”

Taigué Ahmed

JBJ: Have you never been tempted to have refugees you met in the camps take part in the production themselves?

TA: The initial idea was to have refugees playing the piece themselves. But the problem now is visas and the status of refugees in Europe. Would African refugees get visas to travel to Europe to perform as dancers on stage? This a tricky question; the challenge we have been struggling with unsuccessfully since 2016. We tried. We delayed the project until 2017. But the only solution left was to do it with professional dancers.

JBJ: You have been forced to adapt your original idea to the conditions for refugees to come, or rather not come, to Europe; and the conditions imposed by the festival?

TA: Yes, that’s exactly it. Not so much the conditions imposed by the festival. We have a diplomatic issue, an administrative issue, a question of visas. Because as far as the production companies are concerned, the ones on the project are all in favor. They want the refugees to come as they are. They’ve been working together for ten years, and they have all trained as dancers, but the issue is all about visas.

JBJ: You don’t think the project has changed too much; that it has lost its meaning?

TA: No, it’s all part of being an artist. Being caught up in an idea, expressing yourself, performing as yourself and on behalf of others.

JBJ: We started this interview with the fantastic surprise about the TURN funding that will finance the project for you. But your story begins long before that, the story of how you became a professional dancer, the story of your childhood. I read in your biography that you started dancing when you were 13 with a group of traditional dancers and that around 2003 you had your first contact with contemporary dance. Can you tell us what happened before you were 13?

TA: Yes, before I was 13, the story could have happened anywhere else in the world; in these wars between people of the same country. The population of the same country, the North and the South. So, there was the Chadian president François Tombalbaye from the South, who was ousted by the people in the North. And the president from the North, who was called Hissène Habré, sent his forces into southern Chad to exterminate little boys, children, and men–all the men because he wanted his revenge. Maybe some of the soldiers had committed war, it’s a question mark, we don’t know …

JBJ: Do you mean “war crimes”?

TA: Crimes, yes, crimes. We don’t know. But when I was a child, with my mother, there were eleven of us in the family: two girls and nine boys. So, nine boys–I was the smallest and my mother dressed me as a girl to save me from the soldiers while all my other brothers were hidden in a hole between the walls that divided our house from the neighbor’s. The hole was covered with a tin sheet and that’s where they all hid. At that age every child, including me, had seen bodies everywhere, bodies of people killed by the soldiers. That story left a deep mark on me at the time, but as the years went by, the war kept on, rebellion and then war, more war. And war turned into a kind of theater for Chadians. Nobody fled the war. Not the ordinary people, nor the rebels, nor the government forces; no one fled. People would sit in the cabarets or bars and have a drink as if nothing were happening. There’s no market, but everyone goes out and watches the soldiers shooting each other. And that is what drove me and made me into an artist. Why not denounce this story, perform it, express it through dance? And show it to people in another world who don’t know these problems? That is why I created a solo performance called Spit My Story, which tells the whole story from my childhood until I was 30. That is how I came to show the situation in other African countries: in the Congo, in Mauritania, in Equatorial Guinea. Every time I do the show, people come up to me, people I discuss the piece with because they have been through the same thing. For me, it is a bit like therapy, which lets me talk about what happened; let me get it off my chest. That’s it, really. I’ve been performing this show for years and I am happy that I’ve been able to tell others what happened in Chad. And what is happening in Africa.

“…war turned into a kind of theater for Chadians. Nobody fled the war. Not the ordinary people, nor the rebels, nor the government forces; no one fled.”

Taigué Ahmed

JBJ: You talk about this experience very modestly, as if you were just passing on information through the medium of dance. But at the same time, your goal is artistic. How do you perceive this relationship between the artistic aspect and the notion of healing, of release from trauma, of listening to oneself?

TA: When I say that, I’m also thinking of the hate that takes hold of you when you have lived through these really hard things that you can’t communicate to others when no one is willing to listen because everyone has been through the same thing. And no one outside Africa wants to listen either, no one you could tell, no one you could talk it over with to set you free. So, the only thing left is art as a way of reaching other people and communicating to one, two, or three other individuals. By passing on this story through dance and putting it on stage in front of an audience. For example, there is a production where I use dance and music, but the music is composed entirely of helicopter noise. The audience wonders why a helicopter, just helicopter noise running through the whole piece? It’s a question, but it’s also a reality that the audience members are discovering because in their own daily lives they hardly ever hear a helicopter all day long. In Chad, for us, it’s all the time. You hear it taking off and flying all the time. So, all the time, just like music, hence the question, why the helicopters?

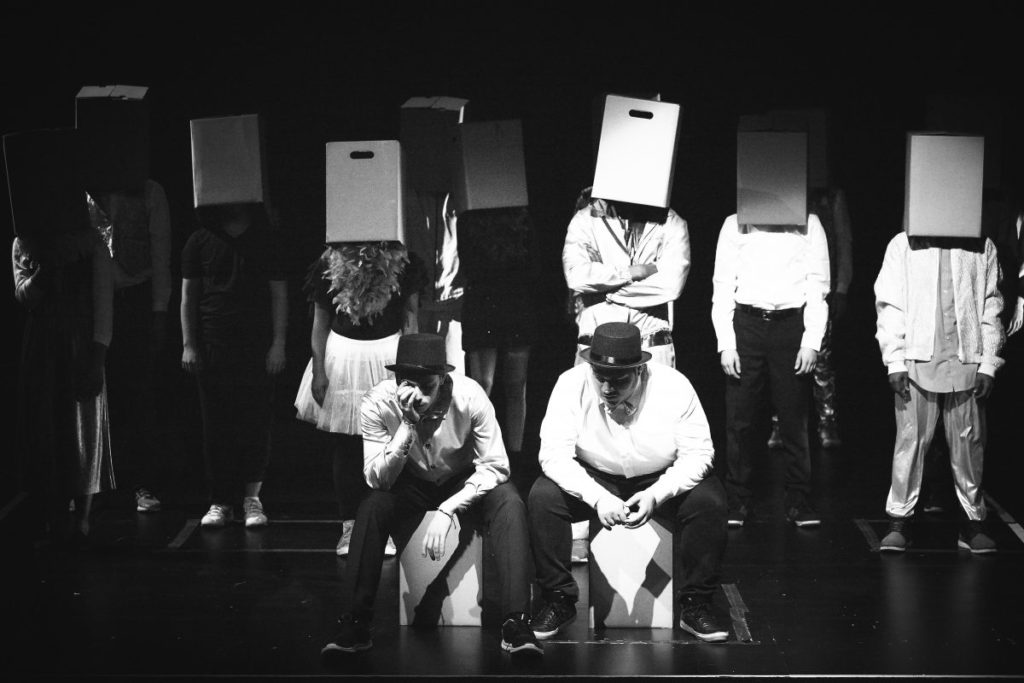

Image by Ramona Reuter

- Image by Ramona Reuter

- Image by Ramona Reuter

JBJ: And is this piece only dance or are there words, a story with a text?

TA: It’s a dance piece, but texts are also available in Kabalaye, my mother tongue. Even so, when I recite the text in my language, I get the impression that people understand me because I repeat everything I say because I’m always saying the same thing. In Chad, we kill each other and we can’t manage to rebuild the country. We can’t even manage to build schools for our children, or implement democracy. And we can’t manage to get together, North and South, to share our common resources. So there are texts, but I recite them and when I recite them, even in Chad where there are people who don’t understand this language, everyone gets the feeling that there is something …

JBJ: … an intention? So, if we take this piece or another piece like Abbanay Abbanay, are they all connected to your own story?

TA: Yes, Abbanay Abbanay is also connected to my story, to the story of my family, which is also the story of all African families, because in a family we always see the father being the head of household, the one in charge. But we don’t see the position of the mother, which is very important. The mother, who looks after the children, who does the housework, who does everything she can to feed her children. And the father, for me, my own father, is totally involved in his own life as a man: free to go and drink alcohol, to come back and shout at the children. It’s something that marked me deeply. And I want to pass on this message via dance to the fathers of other children so that they realize. Because in the streets of N’Djamena, there are children left to their own devices and all these children have a family as well. What do we have to do to link this story with the story of these abandoned children? I worked with a dancer who had been through the same story with his parents. I had him tell his own stories. In the same way, I questioned a musician who works with us, because we are fathers ourselves. In the beginning, these stories were completely different from each other, but in the end, the stories link up, as is so often the case in Africa. The mother is always the one who is the closest and most involved, the person who worries most about her family and for whom her child is everything. But a father could also protect and look after the child, and not say: “Hey, I can do what I like, I can go off and have a drink, I can come back at any hour of the day or night and shout at the children.” That story … knocked me off my feet when I directed it.

JBJ: What does Abbanay Abbanay mean?

TA: “My father, my father.” A lot of people think it isn’t right to be critical about a subject like fatherhood in a piece and share that in public. My response is: No, it is right. I will be a father one day too, it’s right. I will be a father, and you will be fathers–we can’t hide things that cause problems and that aren’t working in families.

JBJ: And what do mothers say, or sisters or daughters?

TA: Mothers? A nun who saw the piece told me it was very therapeutic and it would be good to tour the villages with the show. But how can we go on tour? I mean, there is a big problem with contemporary dance. You have to raise awareness. People have to understand what contemporary dance is. They don’t know the first thing about it, so it’s complicated.

JBJ: You work for an audience who doesn’t understand the language you use to express yourself–the language of contemporary dance?

TA: At least the person should be able to read the text, even if they don’t understand the language of contemporary dance. We give out the text to the audience who have it in their hands and can read it while they watch the piece. After that, you might have discussions. They are maybe going to say, “We didn’t see that.” But we can discuss that too. On the other hand, if there is no text, or if someone can’t read, there won’t be any discussion because they won’t understand.

Image by Ramona Reuter

JBJ: So, the audience needs to have the text to be able to follow your work? You don’t tell the story?

TA: No, I don’t tell the story. I dance for the audience, even if they don’t know the codes, because there are codes that help people understand. But it depends on the audience. If, for example, I do a piece for a professional audience, it will be completely different. In the beginning, in the camps, when I did a piece, I wanted them to understand something.

JBJ: Why did you decide not to tell the story the way a “griot” would do it, but rather by dancing and using a language that isn’t immediately accessible to the people in front of you

TA: Because for me the language of the body is a tool. The interesting thing is telling a story with your body because then you are also healing the person who is telling the story …

JBJ: … telling the story by dancing …

TA: … yes, if I express myself through my body as I dance, it is also therapy. It’s therapeutic for me, and the secondary target is the people in the audience who are watching me; trying to understand the story in their own way. Otherwise, if I were too detached, I would just be telling the story itself, or I might sing it. But the best thing for me is to express it with my body.

“Yes, physical exhaustion is like therapy, and I don’t regard the repetition of movement as a repetitive dance form.”

Taigué Ahmed

JBJ: At the beginning of the interview you mentioned your pedagogical method. And then when I hear you talk about it and say, “No, it’s not via the text, no, it’s not via the spoken word, it’s via the body, it’s via movement.” Is that an aesthetic principle and a pedagogical method at the same time?

TA: It’s the pedagogical method too, but that really takes time. It takes time to get through to the person. I mean, if I work with a refugee, for example, and I am told he is very violent. They advise me not to work with him because not only is he violent, but he’s also armed. Then they say it’s up to you. I see the person and I put him in a group with some people who are violent and some who are not. I put him in the group. He does the work, he is violent, I know that. His character, his state of mind, everything proves that he is really violent. And I make him work just like the others, but I make him work physically as well. Work with the body is also about preparing a person. I prepare him so that he is ready to dance, ready to unwind, and to sleep afterwards. Relax and sleep. All the stuff he’s been through and the stuff that upsets him is that he doesn’t get enough sleep. He has been through a lot and working with his body allows him to unwind and to sleep.

- Dance workshop with Taigué Ahmed in Chad, Image by Christine Cayre Rey, 2011

- Dance workshop with Taigué Ahmed in Chad, Image by Christine Cayre Rey, 2011

- Dance workshop with Taigué Ahmed in Chad, Image by Christine Cayre Rey, 2011

- Dance workshop with Taigué Ahmed in Chad, Image by Christine Cayre Rey, 2011

- Dance workshop with Taigué Ahmed in Chad, Image by Christine Cayre Rey, 2011

- Dance workshop with Taigué Ahmed in Chad, Image by Christine Cayre Rey, 2011

JBJ: I’ve seen two of your performances. One at Schauspiel Nord, Stuttgart; the other here at Solitude. In both cases I saw that you kept going until you were exhausted and that it’s an important part of your work on stage. Carrying on until you drop, to forget. Is physical exhaustion a form of therapy?

TA: Yes, physical exhaustion is like therapy, and I don’t regard the repetition of movement as a repetitive dance form. When you see the same movement for a long time, that expresses several things, representing in different ways an action that does not take place directly on stage. Exhausting the movements is something I often do, and what it means to me is that I am putting myself in the place of this person, and look, this is what he wants; this is the message I have been getting from him all the time. That’s what exhaustion is about.

JBJ: When you say that, are you talking about yourself as the dancer on stage, or as a person representing something you have seen through dance?

TA: About myself as a dancer, in an exchange with what I have learned and seen in my life. It is what I have heard when talking to young people, to refugees there and here. I hear the same stories repeated and going around in a loop. And when I see people in town, I see the same actions repeated, and even that exhausts me. It’s exhausting to see someone sitting begging, seeing that he will be sitting there. You might see him at two o’clock or at eight o’clock, and you come back at six in the evening and he is still there. Exhaustion is that, too. You walk by and then you come back and see him, and you say to yourself: but doesn’t he get exhausted? Can’t he move? Or maybe he can’t …In other words, everything is repetitive, everything is exhausting. That is the sense in which I use exhaustion on stage.

JBJ: And the other dimension that you are describing is another perception of time, as an outcome of the repetition and the exhaustion?

TA: Yes, it is about time, as I observe it, as I see it everywhere. For me, as a dancer, this exchange exhausts me, this thought, this look, it exhausts me. I would like to be on stage and to dance it, but I can’t. I can’t dance what I write. For example, where I come from, there are people who say what I do isn’t dance! There are even people who say, “It is very physical, your stuff is more like karate, like yoga, it is really very physical. How do you manage it?” I reply that it comes from the text. Sometimes, if I am reading a text or if I am working on a text, I can’t get away from it. My body is stuck, stuck in the text. Even if I want to create other movements, I’m not able to. I have tried to create movements that are more danced, but I don’t see myself doing it because what is real is what my body imposes on me.

JBJ: From the start of this interview we have been talking about you, about a unique adventure around you, Taigué Ahmed. But over the same period, you have set up a number of structures, like the Souar dance festival in N’Djamena, and the ensemble Ndam Se Na. I also know that you’ve been thinking about founding a school. How do you explain the relationship between this personal adventure and the social and political commitment that needs structures like a festival, a company or a school? Is it the same Taigué Ahmed doing both?

TA: Yes, everything is connected and it all originates in my work in the camps. The basis of what I do is the workshops that were set up in the camps with the refugees. I created a workshop that lasted three months. I also organized a meeting between different camps and I would really like that project to continue.

- Jean-Baptiste Joly in conversation with Taigué Ahmed, Images by James Nelson, 2017

JBJ: In which camp and which year?

TA: At the end of 2005, 2006, for the Central African refugees in the Amboko, Gondié, and Doyessé camps. I started in three camps. Then I launched the three-month workshop, one month in each camp, and I created the encounter between the three camps. Building on that outcome, I matured the project by continuing to train them as dancers while wondering how to get them performing on stage if I kept on with their training. Should they only appear on stage within the camp or should they dance outside, as dancers rather than refugees? I dreamt of them meeting other professional dancers, Chadian ballet dancers and choreographers who would come from elsewhere to run workshops and help open them up to the world of dance. This is how I started the N’Djamena festival in 2007.

JBJ: With them?

TA: I created the festival for them in 2007 by inviting professionals from Senegal, from France, and Chadian dancers. So they watched the professional shows and they took part in the workshops. The first contemporary dance workshops were facilitated by a French choreographer who I brought over from Poitiers, Gérard Gourdot. From there, the idea of the festival transformed itself into a biennial so that the refugees could continue to work with dance and to perform on stage. And in the three camps, with the refugees, we created the three companies, their own companies, and we held free elections to elect the chairperson, the choreographer, the equipment manager. One of them was a well-educated person in charge of writing letters and offering to come and perform in the surrounding villages. There is a proper course to train them to function without always having to rely on Taigué and his company to make things happen. And the idea for the festival already contained the seed of an idea that creation is artistic and they should perform and participate in the festival like real dancers. In this festival, we can create a space for other teachers and other dancers to come to Chad from neighboring countries. And also, thanks to the Chadian dancers, we can offer a training space, which is one of a kind in Central Africa, including in the Congo or Cameroon. Just like people go to Senegal to train …

JBJ: You mean at the Ecole des Sables?

TA: Yes, that’s right. But don’t forget that the flight from N’Djamena to Dakar is more expensive than from Chad to Germany or France. So why not create this space for reflection locally in N’Djamena, with a little library and somewhere for people to work and reflect together? Make a living space that is simpler than a school, but has a lot of resources. Seek out other partners who might send teachers or exchange choreographers. That’s the idea taking shape now, but it needs time to grow.

JBJ: We have almost come full circle. The ideal would surely be if the professional dancers invited to participate in the project with TURN funding from the Cultural Foundation were the ones you trained from the start in Central Africa, right?

TA: I would be delighted, not only for me but also for them, if I could help them discover the professional scene in Europe, and a different audience. And in exchange, they could talk about their experience in a camp.

JBJ: And they would be able to travel at last?

TA: There are ideas, there always will be–the solo show will go on because I will find the resources. Sarah Israel and I have thought about creating a new piece as a sequel to I Come From Nowhere.

JBJ: Thank you very much for this interview, Taigué Ahmed.

Original transcription: Stefanie Bäuerle, Anna Ohlmann, Translation: Kate Vanovitch

This article originally appeared in Schloss-Post on September 12, 2017, and has been reposted with permission. The original article, as well as the French version, can be found here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Jean-Baptiste Joly.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.