Productions of Broadway musicals have body issues. Full stop. From casting norms for Broadway choruses to the use of fat suits in Hairspray and Jennifer Holliday’s well-documented struggles with weight in relation to her Tony Award-winning role as Effie White in Dreamgirls, Broadway musicals have perpetuated questionable—to say the least—body politics for decades. This troubled history is precisely where Ryan Donovan’s new book, Broadway Bodies: A Critical History of Conformity (Oxford University Press, 2023), intervenes, offering a rich in-depth study of musical theatre, casting, and body politics.

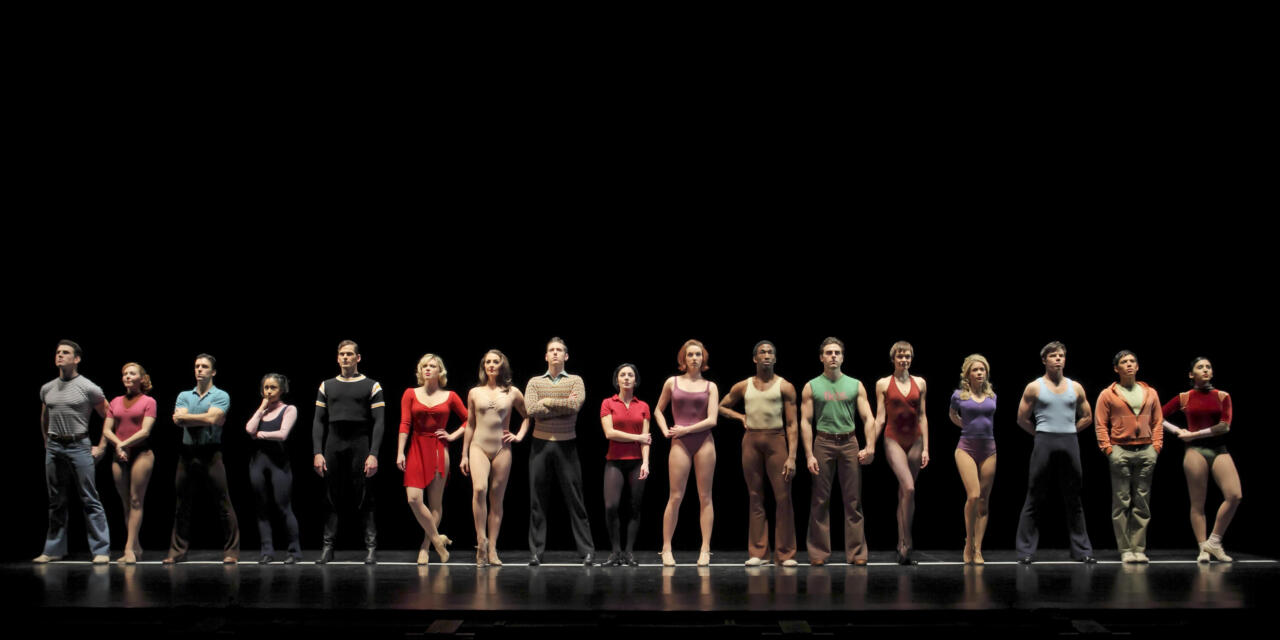

The Broadway community paints itself as being an inclusive and welcoming space. Yet productions of musicals on the Great White Way reinforce how Broadway is indeed a conservative institution. Broadway casting practices largely uphold systems of power and oppression: ableism, fat phobia, heterosexism, misogyny (and misogynoir), and, of course, white supremacy. When audiences think of the “Broadway Body” they largely imagine a “hyper-fit, muscular, tall, conventionally attractive” person who also happens to be a triple-threat. And this shouldn’t be surprising. This concept of the “Broadway Body” is a direct result of aesthetic, economic, and sociocultural factors that occur as a result of the aforementioned systems of oppression.

Broadway Bodies is an excellent musical theatre history that will be of interest to a wide range of musical theatre fans and theatre scholars. Donovan offers detailed histories of A Chorus Line, Dreamgirls, La Cage aux Folles, and Spring Awakening while offering comprehensive overviews of body conformity, fat phobia, misogyny, queerness, and dis/ability in a wide range of landmark musicals. As Donovan notes, while the histories in Broadway Bodies may be shocking today, many of these stories didn’t elicit much press when they occurred. Such is the Broadway machine. With this in mind, Broadway Bodies offers readers a chance to redress their musical theatre history and gain further insight into some of the most artistically, critically, and commercial musicals of the last five decades.

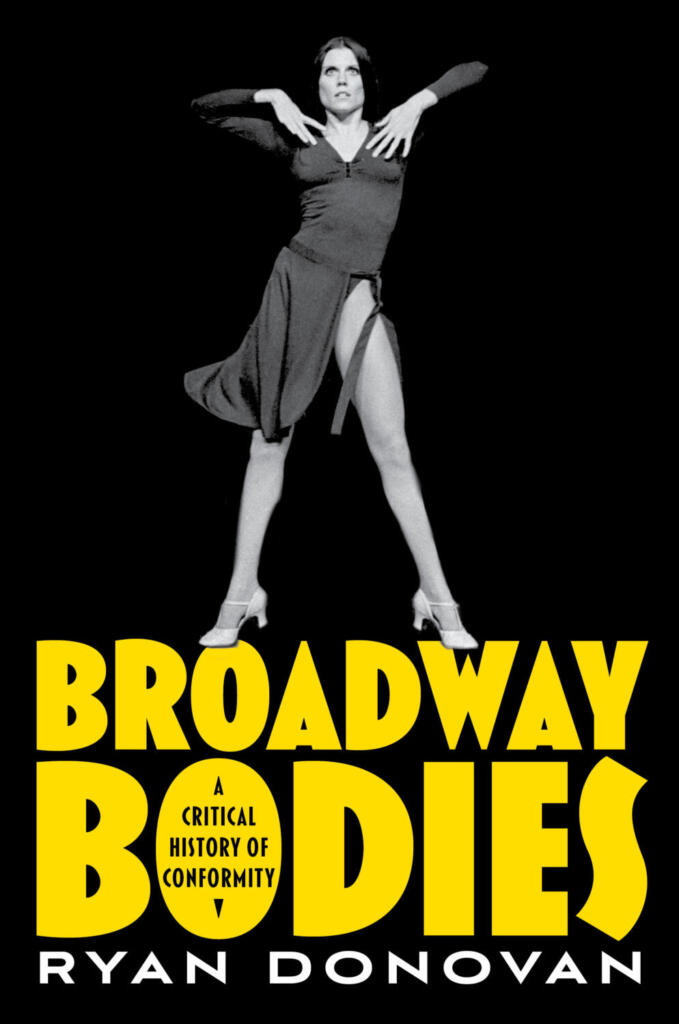

“Broadway Bodies” by Ryan Donovan.

In this interview, I chat with Ryan Donovan about the process of writing Broadway Bodies, Ann Reinking’s intervention as the first replacement Cassie in the original A Chorus Line, and the ongoing conversation about Broadway’s unhealthy obsession with Broadway Bodies.

Trevor Boffone: Tell us about Broadway Bodies. Why this book? Why now?

Ryan Donovan: I wrote the book I wanted to read. As I was writing, I realized that my anxieties about its relevance were sadly for naught—it’s not like the fat phobia, homophobia, and ableism in theatre that I was writing about were suddenly going to go away or get better in one fell swoop. This was both a depressing realization and a motivation to get the book out in the world.

TB: Like so many books, your work on Broadway Bodies began far before you entered grad school. Can you tell us more about your experiences auditioning for Broadway musicals? How did your first-hand experiences inform your understanding of Broadway and your research later on?

RD: Well, they were all unsuccessful for starters! Kidding aside, what I learned while auditioning and performing professionally in musicals all informed the research. Things I witnessed or experienced set me up to ask the questions the book answers. My impetus then for writing the book was to make this history part of the record. It’s putting down on paper what the accepted norms of casting were for a very long time. The book has so far resonated with more than a few readers who have told me that they quit theatre because they didn’t think there was a place for them in it. They “could see who they were hiring,” to quote A Chorus Line.

TB: You began working on this book in 2016. What have been the “ah ha” moments since you began?

RD: Interviewing casting directors was, in a roundabout way, kind of reparative for me in that as a performer, I didn’t quite grasp that they were not usually the antagonist I supposed they were at the time.

TB: What about the challenges?

RD: Trying to finish the book without access to archives during lockdown was probably the biggest one.

TB: Okay. Let’s talk about that cover! What drew you to the image of Ann Reinking in A Chorus Line? What does Ann Reinking tell us about Broadway casting and conformity?

RD: I studied with Ann as a young performer for two summers and later auditioned for her. She was kind of a touchstone and avatar for many of us who were lucky enough to work with her, and so putting her on the cover was personally meaningful to me. It calls back to the younger version of myself just before I moved to New York to try and make it as a dancer in musicals. In terms of the book, though, much of the book is not just concerned with casting but with recasting the musicals I write about and how the economics of musicals invited this kind of conformity because producers needed them to be replicable to make money, which in turn changed the demands for performers.

Reinking, of course, was the first replacement Cassie in A Chorus Line, and though she was pretty different than Donna McKechnie, the role’s originator, I argue that following that first replacement cast, the replicability of the original cast became part of the show’s modus operandi. This wasn’t, however, only born of economic imperatives: Baayork Lee, who has staged nearly every major production since 1975, notes that for her, casting the show is about paying tribute to her fellow original cast members and honoring them. It was important to me to avoid what writer Chimamanda Adichie calls “the danger of the single story” and to note the multiple, often conflicting perspectives on the situations I covered. Paradox and complexity are more interesting to me as a historian, writer, and reader than opinion.

TB: I can’t help but bring up Ramin Karimloo’s recent interview with Playbill in which he noted that the term “Broadway Body” is problematic. What did you think about Karimloo’s comments?

RD: What’s so fascinating about that interview is how the so-called ideal Broadway Body is now the very one that actors like Karimloo want to distance themselves from. This distancing reflects the body politics of our contemporary moment, but it also recalls something I wrote about in the book, which is how thinness became framed as a problem for some actors who played Effie in Dreamgirls and raised questions of whether or not they would wear fat suits. The phrase “Broadway Body” has been around since at least the 1980s, but only became more widespread in the industry in the past decade or so when Broadway-focused fitness companies began to use it. It’s ironic now that someone like Karimloo, whose body, from all appearances, would have little issue approaching the Broadway Body ideal, bends over backwards to avoid association with or propagating it.

The point I’m making in the book is not that the Broadway Body itself is or isn’t bad or problematic, but that the idea of it has material consequences that unintentionally (in most cases) perpetuate the exclusion of a vast array of bodies from participating in musicals—and that is what I would suggest Karimloo is recognizing by distancing himself from it. And that seems like an interesting marker of progress toward a kind of body neutrality.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Trevor Boffone.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.